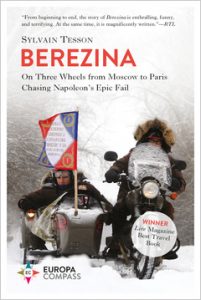

Retracing the Historical (and Literal) Path of Napoleon's Retreat from Russia

Sylvain Tesson Attempts to Journey Back to 1812

My insomnia was populated by visions of crumpled sheet metal. All night I’d tried to fall asleep. I was always more tormented by the prospect of traveling by motorbike than by the idea of a long stay in the forest, or plans for a mountain climb. I could never sleep the night before getting on a bike. You’re much more at the mercy of destiny’s irony on the road than amid the wilderness of nature. A pothole, a truck that’s too wide, an oil puddle: you’re dead before you’ve had the chance to do anything. I switched on the light and looked at the map on which the itinerary of the 1812 campaign was reproduced.

Napoleon should never have approached the splendor of Moscow. Its glare was too powerful for him. Some beauties are forbidden. In strategy as well as in love: beware of what sparkles.

On September 14th, 1812, his eyes on the onion domes, he contemplated the third Rome from the top of a hill. The following day, he positioned his rear guard behind the Kremlin ramparts. I believe in dharma, in the wheel of destiny. There are times when an apparently trivial event triggers a series of unexpected occurrences. That day in Moscow, a chain of causalities was set off that, two years later, was to sweep away the Empire.

There were soldiers who thought that Moscow was just a stage on the way to India. They imagined they would go as far as Mongolia to “take hold of British possessions,” as Sergeant Bourgogne writes.

The soldiers of the Grande Armée would have followed to the ends of the world this emperor who had covered them in glory in Egypt, Italy, Prussia, and Spain. They had no inkling that, this time, their idol had led them to the brink of a nightmare.

Had Napoleon really wanted this hazardous war? Had he truly wished to send his men into the shapeless territory of a birch-covered plain where the Cossack and the pitchfork-wielding Moujik prowled? Alas, for him, the campaign against Russia had become inexorable. Had Alexander I, his friend and brother, not violated the Tilsit Treaty signed in 1807? What remained of the Tsar’s commitment to join the blockade against Britain? Nothing! The Russian sovereign had opened his harbors to British ships and was trading with perfidious Albion. The Emperor of the French could not leave this betrayal unpunished.

The Tsar had to be forced to renew his promises. The secret bonds between Saint Petersburg and the British had to be severed. This last effort had to be made and this ultimate capitulation obtained in order for the blockade against London to be successful, and therefore complete the great task of European peace. “Spain will fall just as soon as I have destroyed British influence in Saint Petersburg.”

Napoleon was venturing into the immensity of this continental power in order to vanquish his sea rival! He outlined to his peers the advantage of a show of strength before Alexander I. He was thereby inventing—200 years early—the equation that supported the Cold War of 1945. “The reputation of weapons is entirely equivalent to actual power,” he told his marshals.

Shortly before the start of the war, a strange event should have warned Napoleon that dreadful omens were accumulating in his horoscope.

To display your fangs—that is, muskets, cannons, and cavalry sabers—would be sufficient. Impressed with the deployment by the River Neman and terrified by the prospect of charging cavalry, the Tsar would capitulate at the first jingling, resume his favorable disposition, and restore the alliance. A strange war that consisted in thrashing an adversary in order to turn him once more into a friend!

On no account would the Grande Armée advance beyond Minsk. Let’s say Smolensk at most. They might even go back to spend the winter in Paris. That was the plan.

What Napoleon had not foreseen was that Alexander I was no longer afraid. The Tsar had changed. He was following different maneuvers and had made new friendships. Britain, Sweden, Austria, and even the Ottoman Porte were now Russian allies. Saint Petersburg had become the anti-Napoleonic salon where the future members of the coalition were preparing for 1814.

It was 5 am. There was silence in Jacques’s apartment. We were drinking black tea, delaying the moment we’d be going out into the freezing air, feverish from lack of sleep, and I was telling Gras that Napoleon was not the guiltiest party in the 1812 affair. Something that relieved us of the remorse of commemorating the campaign.

“Oh, that’s Sokolov’s theory! I read his book in Donetsk.”

“Sokolov?” Goisque says. “The man who thinks he’s Napoleon?”

Oleg Sokolov, history lecturer at the University of Saint Petersburg, devoted a cult to the Emperor. Every year, he organized historical reconstructions. Thousands of extras in helmets, boots, and 1812 costumes would re-enact the battles. He would wear a bicorn and command the maneuvers. He published Le Combat de deux Empires: la Russie d’Alexandre Ier contre la France de Napoleon – 1805-1812 in which he concealed nothing about Alexander I’s responsibility in the Franco-Russian war.

He highlighted the Tsar’s betrayal and Napoleon’s efforts to bring him back to his Tilsit promises. This way, he had attracted the wrath of his readers. Sokolov had broken a Russian rule: History is a delicate science and you must never speak ill of your own people, even if you’re telling the truth.

We were now in the garage. An electric coffee pot stood on the back seat, steaming, lit by an oily light bulb. Vassily was busy welding some undefinable parts. We crammed our tools and baggage in the trunk of the sidecar. We were ready to set off. The Ural looked ready too.

On June 25th, 1812, the Grande Armée had crossed the Neman. A column of 450,000 men had gone over the river, carting a thousand cannons over the ford. It was the same river where, in 1807, Alexander I and Napoleon, sheltering in a tent erected on a raft, had signed the Tilsit Treaty and sworn mutual peace. Five years later, fate had brought the Emperor back to the banks where this agreement had been sealed. Napoleon should have been inspired to reread Heraclitus and hesitate awhile before crossing his Acheron. “No man ever steps in the same river twice,” the wise man of Ephesus said.

Moreover, on the grassy bank, shortly before the start of the war, a strange event should have warned Napoleon that dreadful omens were accumulating in his horoscope. A hare shot through the legs of his horse. The mount swerved and the Emperor—a better horseman than the dreadful Saint Paul—fell, picked himself up, got back into the saddle, and paid no more attention to the incident.

“There’s another hare intervention in history,” Gras, who had read everything and drunk almost nothing, said. “I think it’s in Herodotus.”

“Really?” I said.

“Yes. One day, Darius, the Persian king, arrived before the Scythian cavalry. The two armies faced each other, ready for attack. A hare burst forth from amid the ranks, and the Scythians scattered and chased after the animal. Their hunting instinct had been awakened and they only thought of hunting down the hare. This frightened Darius. If, at the moment of engaging in battle, these men could be distracted by a damned little animal, it meant they were fearless, emotionless brutes. And so the Persians, upon discovering this, turned back.”

“It’s what we would have done,” Vitaly said.

Vassily and Vitaly were Russian, therefore superstitious. If Napoleon had had Slav or Oriental blood, he would have cursed the Neman hare, spat in the wild grass, mounted his horse, and sounded the return to Paris.

“That kind of story can really screw up your plans,” Goisque said.

In the absence of signs and not very au fait with oracles, we stepped on the gas at 8 am on December 2nd, 2012. Nothing could have diverted us from our obsession: to go back home.

__________________________________

From Berezina: On Three Wheels from Moscow to Paris Chasing Napoleon’s Epic Fail. Used with permission of Europa Editions. Translated from the French by Katherine Gregor. Copyright © 2015 by Editions Guérin. Translation copyright © 2019 by Europa Editions.

Sylvain Tesson

Sylvain Tesson has traveled the world by bicycle, train, horse, and motorcycle, and on foot. His bestselling accounts of his travels have won numerous prizes, including the Dolman Best Travel Book Award. Berezina is his first book to appear in English.