Resisting the Badge of ‘Resilience’ in the Wake of a Devastating Loss

Emily Rapp Black Considers a Ubiquitous—and Inexact—Description

During the two years Ronan was dying, I unwittingly became the poster child for resilience, a word with which I’ve always had a complicated relationship. “I would die if I were you” I’d hear at the grocery store, or in the pharmacy line as I waited for Ronan’s seizure medication to be mixed and bottled. “You are tragic, he is tragic, it’s all so tragic.” I’m sure I was polite, or maybe I wasn’t, but inside I was railing, reeling. My secret desire was to punch these strangers in the face. A few times I came close to doing just that.

Tragedies are narratives with no place to go, no alternative endings to choose or create. No open doors, no thresholds, no light. They are narrative prisons, and I didn’t need or want to be reminded of that when each day my son’s life disappeared into a lightless, impenetrable, locked-down cell that I could not enter to provide comfort. He suffered; I could not relieve it. In the next breath, these same people (well-wishers?) would praise me, which felt as jarring and disorienting as being labeled tragic. “You’re more resilient than you know.” “This is a test of your resilience.” “You can do it.” “Be strong.”

I was not thankful for the chance to remind someone else about how terrible life could be, or how lucky they were that they had avoided my singular, shitty fate.

“Oh yes,” I’d say. “Yes, of course. Thank you.” And then I’d sit in my car and push my forehead against the steering wheel, enraged and confused, saying aloud to nobody, “I didn’t ask for a fucking test.” I blubbered and sputtered in the hot sun or in the blast of the car heater, snot falling into my lap, sweaty hands gripping the wheel as if I could tear it free. I was not thankful for the chance to remind someone else about how terrible life could be, or how lucky they were that they had avoided my singular, shitty fate. I didn’t want to put other people’s lives “in perspective.” “I couldn’t do it, but you’re so resilient. You’re so strong.” I was not. I was a mess. I was so sad I couldn’t believe I managed to be upright at all during the day. I was also still alive, but the thought of being brave and powerfully resilient for the rest of my life, or held up as an example of strength, left me exhausted and bewildered. That, I knew, was unsustainable, not to mention an inaccurate description of my state of mind and body.

I was so weary of the labels “brave” and “courageous.” From Sonali Dev’s A Distant Heart: Keep courage. Courage. That’s what they kept calling it. This thing they wanted him to keep. But how did you keep something you did not own? Did not know? Could not find in the hungry panic inside you? My “hungry panic,” not bravery or courage, drove me to write. I wasn’t brave for telling my story; I was simply doing the only thing I knew how to do, the only work I’ve ever loved. And I wasn’t doing it because I possessed some extraordinary courage, as if I were holding a glass ball inside my heart, protecting it, caring for it; I was doing it because it was necessary. This was a chop wood, carry water scenario. There were strong and irritating parallels with the “overcoming disability” trope I’d been resisting my entire life. I was applauded for being out in the world with a disability; I was so brave for living in the body I was given, as if I’d been given any other choice.

After Ronan died and I had another baby, I heard the words “brave” and “courageous” again, but I also just as often heard “resilient.” A word like a woodpecker—insistent and impossible to ignore. People continued to congratulate me for being “so brave and so resilient,” for being “so strong.” I was happy, but I was still gutted from the loss of my son, from the way in which he died, from the manner in which my previous marriage ground to an unexpectedly acrimonious end. I wasn’t strong, and I wasn’t brave. I was not in a war, and I wasn’t fighting any battles. Couldn’t I just be a normal human being who had suffered a traumatic loss? Wasn’t it enough to still be moving through the world and stringing words together? Wasn’t that, in fact, the story every one would live if they survived long enough to lose a beloved?

Couldn’t I just be a normal human being who had suffered a traumatic loss? Wasn’t it enough to still be moving through the world and stringing words together?

So the word “resilient” didn’t fit. It was as if I’d put on a dress that didn’t suit me, and when I walked out of the dress- ing room everyone told me how great I looked, and I knew these compliments were lies. The word was a badge that had been pinned to me, only I hadn’t earned it, and had no interest in doing so. I just wanted to live my extraordinary life in an ordinary way, as we all do. What did it actually mean to be set apart or made special in this way by this particular word? Words, of course, carry great power. Emily Dickinson said, “I know nothing in the world that has as much power as a word. Sometimes I write one, and I look at it, until it begins to shine.” Or, in my case, I had looked at and heard the word so often it had become a burden and was beginning to rot.

I started to hear about resilience everywhere, it seemed, and I realized that the word has become so much a part of the vernacular as to have practically become interchangeable with “strong” or “tough.” It is used widely and indiscriminately to describe everything from cities, politicians, children, and marriages to social movements, fabric, diseases, and even cells and tissues of the body. It is understood (or perhaps misunderstood) as a synonym for “grit,” or “perseverance,” as a character trait that stems from a person’s individual will, from a self-directed ability to “bounce back.” The word is deployed as a diagnostic tool for all kinds of situations, set forth as an achievable goal or state of mind, touted as the solution to all sorts of problems, from communities struggling to recover after an earthquake, to “at-risk” kids fighting to succeed despite education in subpar, underfunded schools.

When I stepped back from the bridge in Taos, I made a decision to live, although I had no clue—no map—of how to begin that journey. “You’re so resilient; you’ll find a way.” This wasn’t helpful or encouraging. Brave. Resilient. Strong. These are just words, but of course words are never just words, and truly understanding a word is not just a matter of semantics.

If the words “strong” and “resilient” and “brave” were treated as nearly interchangeable, did that mean they were, in fact, synonymous? No. That didn’t feel right. Even if the words had similar meanings, none of them fit what I was or felt. What I wish I’d said to those people who described me as resilient when Ronan was dying: I can’t do it, either. I almost didn’t. And then, after Ronan died, to be applauded again for this mysterious quality of “resilience,” the sign of which was an equally mysterious state of “moving on,” which could be detected in what way? Through my perceived happiness? Also incorrect. I could spend a lifetime trying to “come to terms” with what happened, and I would always fail; to succeed would be to kill off that other mother who had chosen to live, to strap myself to those train tracks on a hot midwestern night and let the train flatten me into the ground. To “get over it,” a feat so often expected of those who grieve, was an impossible goal. If I tried to do it I would be unable to do anything at all. I didn’t want to nix “resilience” from my vocabulary, but I wanted to create space around this word, turn it over, turn it around. “The opposite of language is not silence/but space” (Jenny George, “The Gesture of Turning a Mask Around”).

Now, in my current life, on the other side of what was a great fire that shaped and forged me in remarkable ways, I realize what I need to do. I need to dig to the bottom of the word “resilience,” pull it up by its historical and etymological roots and have a look, because if it wasn’t and isn’t helpful to me—if its misuse was and is harmful in some real and fundamental way—then the same might be true for others. Children die every day; people lose their partners every day; mothers and fathers are buried every day. We need this word—it has texture and meat and nuance and shadow and light and blood in it—but we need a better understanding of what it means before we can use it for anyone’s benefit, including our own.

I join my husband, Kent and my daughter, Charlie on the porch, where Charlie is still saving “aminals,” so I kneel behind her, give her a hug, and tell her I love her. “Okay, Mommy,” she says, and turns to face me. “You’re my best friend.” I tap her little freckled nose with my finger and say, “Boop!” which she loves. “You bet I am. Always.” I feel it in me, that uncomplicated, devastating happiness; it is as true and tactile as anything I’ve ever felt. But behind that feeling lurks the panic that the world can drop out from beneath your feet at any time, because that’s true, too. Lightning can strike the same place twice, three times; it can strike you all your life. Knowing this, how do we keep living?

_______________________________________

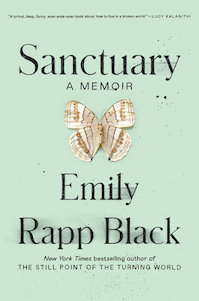

Sanctuary by Emily Rapp Black is available now via Random House.

Emily Rapp Black

Emily Rapp Black is the author of Poster Child: A Memoir, The Still Point of the Turning World, and Sanctuary: A Memoir. A former Fulbright scholar, she was educated at Harvard University, Trinity College-Dublin, Saint Olaf College, and the University of Texas-Austin, where she was a James A. Michener Fellow. A recent Guggenheim Fellowship Recipient, she has received awards and fellowships from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, the Jentel Arts Foundation, the Corporation of Yaddo, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Fundación Valparaíso, and Bucknell University, where she was the Philip Roth Writer-in-Residence. Her work has appeared in Vogue, The New York Times, Time, The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, Psychology Today, O: The Oprah Magazine, Los Angeles Times, and many others. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times Book Review and frequently publishes scholarly work in the fields of disability studies, bioethics, and theological studies. She is currently associate professor of creative writing at the University of California-Riverside, where she also teaches medical narratives in the School of Medicine.