Resistance and Survival: Portraits of Black and Brown America, c. 2020

Mitchell S. Jackson on the Photography of Darryl DeAngelo Terrell, for The Longest Year: 2020+

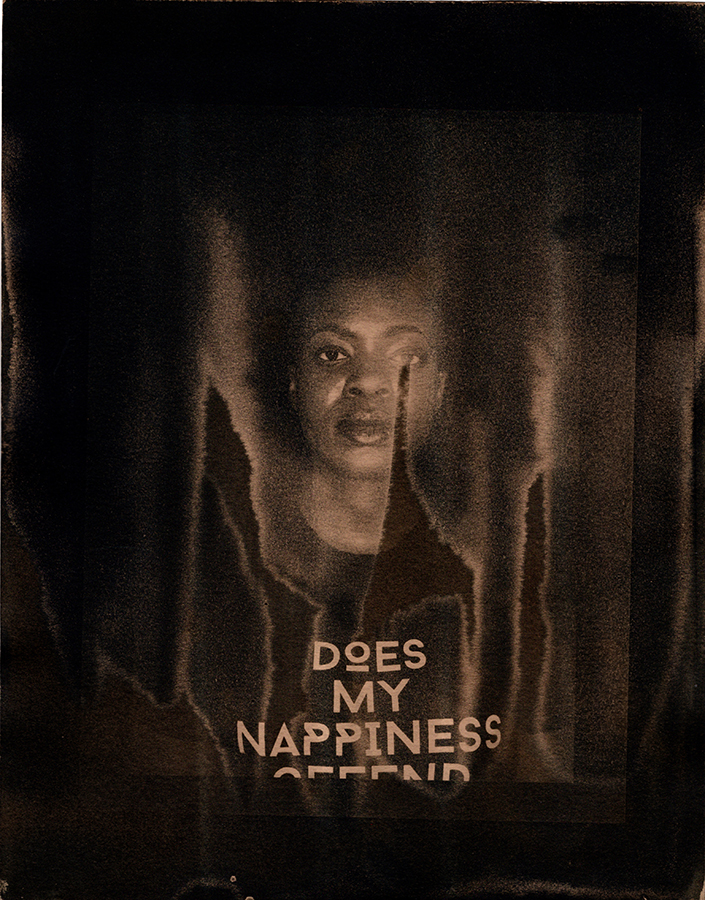

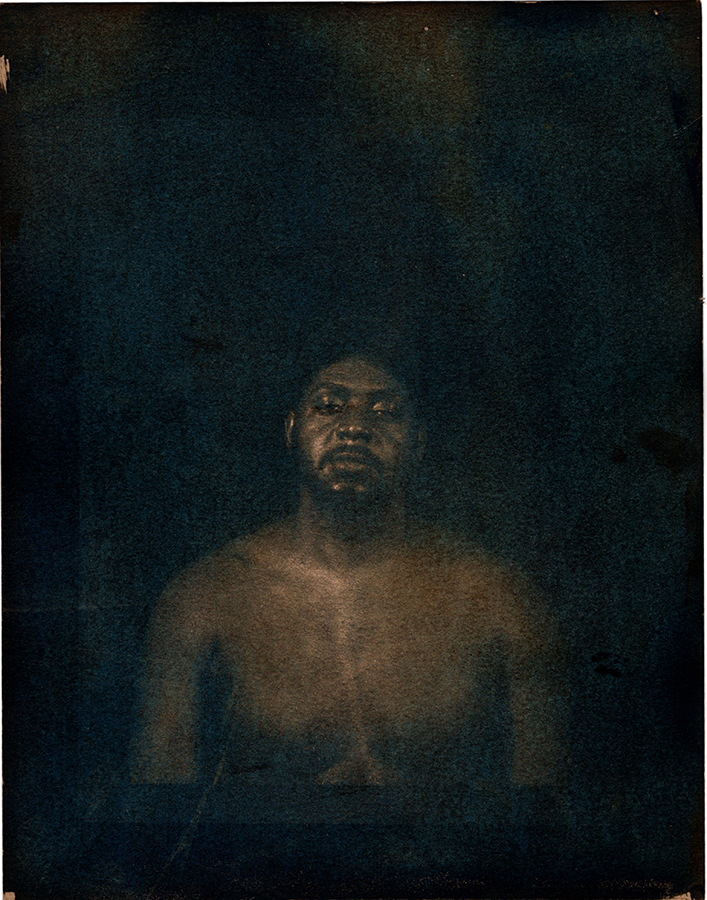

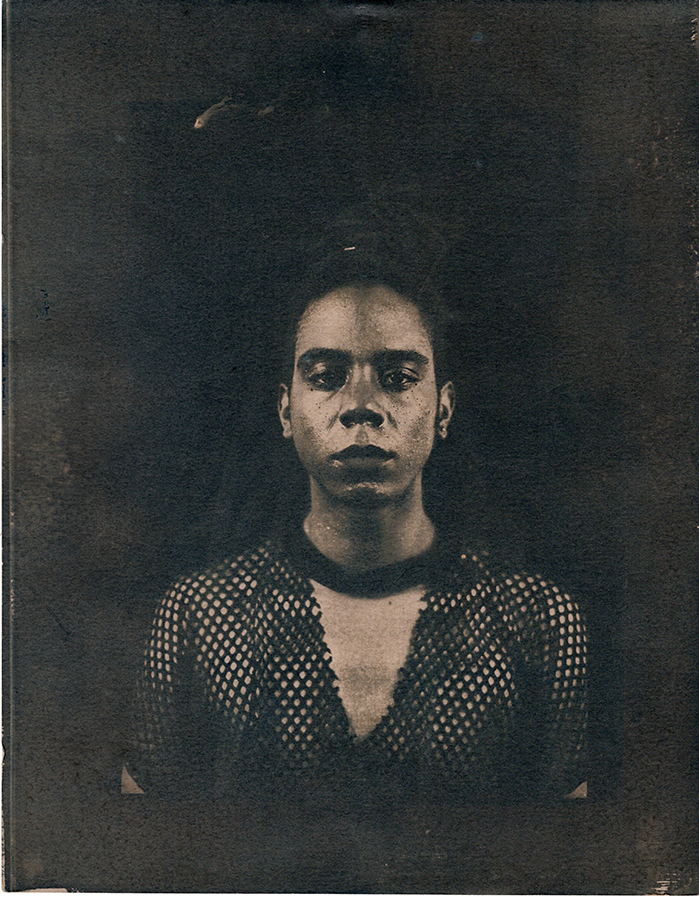

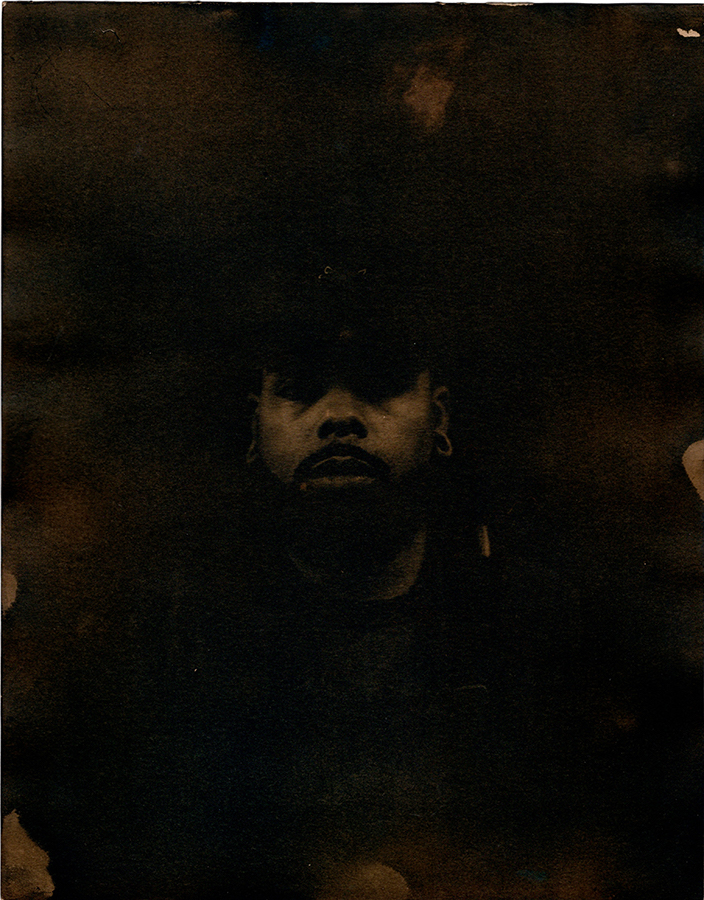

The Longest Year: 2020+ is a collection of visual and written essays on 2020, a pivotal year that shifted our way of experiencing the world. In most publications, images work in service to words—here they work in tandem. // In the fifth in the series Mitchell S. Jackson considers photographer Darryl DeAngelo Terrell’s series, Project 20’s. Says Terrell, of their work: “Project 20’s deals with the resistance and survival of Black and brown people between the ages of 20 and 30. Inspired by my upbringing in Detroit and my love for contemporary hip-hop, Project 20’s comes from two specific songs, “We Don’t Care” by Kanye West from his College Dropout album, and “Chapter Six” by Kendrick Lamar from his Section 80 album. Both of these songs speak about the life of minority youth in marginalized communities; struggling to make a living and to be happy by any means necessary. This topic became more important to me as I found myself making Chicago home and seeing how gentrification and poverty were affecting Black and Latinx youth (i.e putting them in positions that marginalized them even more).”

Project 20’s, 2017–2021, Detroit and Chicago, cyanotype, black coffee, Lipton black tea.

“Look what was handed us

Fathers abandoned us

When we get them hammers,

go on call the ambulance.”

–Kanye West, “We Don’t Care”

*“Young, wild, and reckless is how we live life

Pray that we make it to twenty-one (One, one, one)

Oh, we make it to twenty-one (One, one, one)”

–Kendrick Lamar, “Chapter Six”

*Article continues after advertisement“There is an urgent need for everyone to recognize and

respond to the profound and lasting harms inflicted by gun violence,”

–Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt

*

Rose City Oresteia

by Mitchell S. Jackson

Summer of the year of our Lord 1996—the year I could’ve been a subject in Darrel DeAngelo Terrell’s Project 20’s portraits—I turned 21. Oh what a summer it was in some of the worst ways. Not a raging pandemic but clear and present threats abounded in what we called the NEP (Northeast Portland). As the fates decreed, that strifed summer of ’96 was also my last as a full-time D boy, which is to say, the end of days bending corners in an electric blue Accord, delivering (“hitting licks” was the lingo) crack that I’d cooked and wrapped myself and on more lucrative occasions, weightier hunks of the kilogram I kept stashed.

One night while hitting what would’ve been a nice-ass lick, my customer—a Black dude my age who I’d known for years—and an accomplice jabbed a pistol into my temple and seized what he was supposed to purchase. “You want to die over this shit?” he spit, and I knew at once that I did not want to die and plead as much. However, that night and the weeks thereafter I felt compelled to decide whether I would kill for the breach. And while retribution (the “get back” some called it) would’ve been justified in our fixed cosmos, for reasons that included what I now glean as hopeful rather than hopelessness about my future, I chose otherwise. [continued below]

It’s hard if not impossible to see the Black and brown faces in Terrell’s cyanotype portrait project and not muse on those years that my survival was steeped in precarity. It’s also damn near impossible to see their work without considering the extant circumstances of young people in Portland, Oregon.

Aka The Rose City.

Home.

In this, the year of what Lord has sanctioned such suffering, it’s common for me to hear tales of brazen terror. Matter fact, it happens so often that it surprises me little to learn that a wounded or dead and gone young person owns a face that resembles a face from my youth and /or the surname of an old friend or associate or fellow denizen of the old neighborhood.

Thus far, there have been upwards of 388 shootings (that figure doesn’t include suicide attempts) in my hometown.

Thus far, the city’s annual homicide tally numbers north of 30 victims (23 of them as a result of gunshots).

This violence is both unprecedented and the predictable math of a place founded and maintained as a white Eden.

Would it shock you to learn that in a blanched utopia Black and brown people make up a preponderance of the dead and the ones who did the harm? Would it surprise you that, in a place that has ever included but a scant number of Black and brown folks, the distance is often mere between perpetrator and wounded; between murderer and murdered? Would you dispute that deep despair is the nexus of this generational vengeance?

The black-tea and coffee-stained effects of Terrell’s photos remind me of the darkness hovering my beloved city. But I must also press hope from the truth that in the young souls they photographed—peep the eyes, the eyes, the eyes—I see degrees of whatever light, all those years ago, lead me away from what seemed predestined.

_______________________________

The Longest Year: 2020+ is a collection of visual and written essays on 2020, a pivotal year that shifted our way of experiencing the world. Edited by Rachel Cobb, Alice Gabriner, and Elizabeth Krist.

Rachel Cobb is a photographer who lives in New York City. She has worked for numerous publications including The New York Times, TIME and Rolling Stone magazine. Her award-winning book Mistral: The Legendary Wind of Provence was published by Damiani in 2018. More of her work can be found here.

Alice Gabriner is a visual editor, instructor and mentor with 30 years of experience at publications, including The New Yorker, The New York Times, National Geographic, and TIME. For the first two years of the Obama administration, she served as Deputy Director of Photography.

A National Geographic photo editor for over 20 years, Elizabeth Krist is on the boards of Women Photograph and of the W. Eugene Smith Fund, helps program National Geographic’s Storytellers Summit, and advises the Eddie Adams Workshop. She curated A Mother’s Eye for Photoville and CatchLight, and the Women of Vision exhibition and book.

Mitchell S. Jackson and Darryl DeAngelo Terrell

Mitchell S. Jackson is the author of the widely praised novel The Residue Years and the memoir-in-essays Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family. Jackson has won the Whiting Award, the Ernest J. Gaines Prize for Literary Excellence, and a Creative Capital Award, and been honored by the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Cullman Center of the New York Public Library, PEN America, and more. His writing has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Time, The New Yorker, Harpers, and elsewhere. Jackson’s memoir-in-essays Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family was named a best book of the year by fifteen publications. His next novel—John of Watts—will be published by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Darryl DeAngelo Terrell is a Detroit-based artist who primarily works within lens-based media, and is a curator, DJ, organizer, and educator with an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. They have performed and exhibited work at The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), The Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (Brooklyn), The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, and elsewhere.