Re(se)a(r)ching For Connection: Navigating the Fact and Fiction of Alien Abduction Stories

Ilana Masad: “It’s in trying to reach beyond our limited selves that we are, I believe, most human.”

Five years ago, my partner gave me an incredible birthday present—a digital folder full of scanned documents.

Sound boring? It was anything but. The files came from the University of New Hampshire, which houses the archives of Barney and Betty Hill, the people widely considered to be the first alien abductees and from whose experience an entire genre was born.

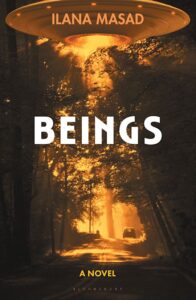

My new novel, Beings, was also born, in part, from their experience. I first learned about the Hills from overhearing a comedy true crime podcast my partner was playing in the kitchen; once my attention was caught, though, I was well and truly hooked. I had never considered the fact that the narrative of alien abduction that I’d somehow come to know by pop cultural osmosis—think bright lights, pregnancy tests, anal probes—had an origin point. I’d certainly never imagined that the origin point rested in two individuals’ very real experiences rather than in some work of fiction.

I realized that what I believed was possible just didn’t matter. What mattered was that they believed it.

The more I learned about the Hills, the more fascinated I became, and the more I wanted to write about them. Though Barney was Black and Betty was white, and though they married years before Loving v. Virginia, little of the coverage of their ordeal dealt with race. I wondered if that middle of the night event on an empty stretch of highway in rural New Hampshire was actually something far more earthbound and unfortunately human. Perhaps they’d been the victims of racist violence, and perhaps they’d suppressed what happened, written over it with a better, if stranger, story.

But then I caught myself. Why was this the version of events I was imagining? What did it say about me and about the culture I live in, that my brain so quickly took me to this place? Wasn’t I doing them yet another sort of violence, or at least an injustice, by refusing to take them at their word, by refusing to fully understand and explore what they said they experienced?

I was deeply disturbed by this, and for a while felt like I absolutely could not, should not, write about the Hills. I would still research them, I decided, but in the service of something adjacent, perhaps, or extremely fictionalized. So I began to read. I read The Interrupted Journey by John G. Fuller, the book the Hills participated in and helped promote; I read Captured! The Betty and Barney Hill UFO Experience by Betty’s niece, Kathleen Marden, and prominent ufologist Stanton T. Friedman; I read The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson, to learn about how Barney’s family migrated north from Virginia to Pennsylvania; I read They Are Already Here by Sarah Scoles to understand more about ufologist communities; I read Passport to the Cosmos by John E. Mack to understand more about the prevalence of alien abduction experiences; I tried reading Chariots of the Gods? by Erich von Däniken, considered a classic of the alien quackery genre (and gave up pretty quickly, in part because of the author’s friendship with Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun, in part because it was just incredibly stupid).

And then, of course, I began reading through all those files that Betty Hill had placed with UNH decades after Barney’s death—the gift from my partner. There’s an intimacy to archival material even when it’s narrowly curated like the Hills’ boxes are: I saw their handwriting, their typewritten letters, their signatures, and the few pieces of personal ephemera that found its way into this archive that documents, more than anything else, their abduction and its aftermath. I couldn’t help but feel closer to them, having seen their penmanship, read their correspondence and drafts of their speeches, and looked at their family photos.

During this process, I changed. I had been an utter skeptic, completely unwilling to even entertain the idea of alien abduction being real. I came to identify with Fox Mulder’s famous “I want to believe” poster, for one, but more importantly, I realized that what I believed was possible just didn’t matter. What mattered was that they believed it. It was real to them. They experienced that realness physically, mentally, spiritually, as part of their lives. Who was I to deny them that?

The longer I wrote, the more I came to realize that even if I’d tried to, I would never have been able to write about the real Hills.

Beginning in this place of belief allowed me to think again about trying to write a version of their story. Still, there was a great irony that I needed to reckon with: the Hills’ lives changed most dramatically not because of their encounter with extraterrestrials, but because a fellow human decided to write about their experience without their consent. They only became public figures because a journalist at the Boston Evening Traveler wrote a five-part series about the Hills that was published in the week before Halloween, 1965, four years after their harrowing abduction experience, and months after they’d completed the psychiatric treatment they’d sought out in order to manage their symptoms of anxiety.

If I was going to write about them too, what could I do differently? How could I honor them, the people they were, and what they went through? How could I honor their own narratives—as documented in the book Fuller wrote with their participation; as maintained in their archives—while still writing fiction, which was the only way I felt qualified to approach them? Was this even possible, or was I going to end up being just another person using their story for titillation?

Instead of shying away from the terror I felt (because anxiety tends to feel in my body very much like abject fear), I decided to write into it, and to acknowledge the complexity I was working with in the narrative itself. This is why the first line of Beings is: This is how I like to imagine them.

The longer I wrote, the more I came to realize that even if I’d tried to, I would never have been able to write about the real Hills. They were whole and complete human beings about whom I ultimately know only a fraction. All I could write was my imagined version of them. In trying to reach across and relate to them, though, I believe I found my novel’s beating heart. We’re all stuck inside our own brains, our own bodies, with our own psychologies and flawed memories and traumas and hopes and dreams; it’s in trying to reach beyond our limited selves that we are, I believe, most human.

__________________________________

Beings by Ilana Masad is available from Bloomsbury Publishing.

Ilana Masad

Ilana Masad is a writer of fiction, nonfiction, and criticism whose work has been widely published. Masad is the author of the novel All My Mother's Lovers and is co-editing the forthcoming anthology Here For All the Reasons: #BachelorNation on Why We Watch.