I cannot fully express just how much hurt and frustration the erasure and misrecognition of women and mothers, especially Black women and mothers, causes me. In my own life I’ve experienced others demeaning me and questioning my abilities simply because I am a Black woman. How many times have men threatened my sense of safety, hollering at me from their cars? How many times have I heard I was given an opportunity only because of the color of my skin? How many times has another person’s looks or comments tried to make me question my worth? I cannot say; there have been too many.

I also cannot tell you how many times people have been surprised by my intellect and my successes because they assume my biggest accomplishment was marrying my husband. My own work has often been hidden behind his, not for lack of his appreciation but because we still live in a world where women of color are not fully seen. Now that I am a mother, this erasure takes place on new levels. I have stood at events right next to my husband while he was congratulated on the birth of “his” son.

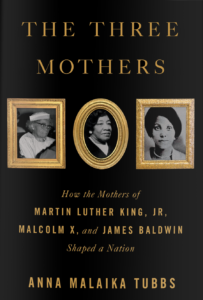

I could list pages of examples from my own life, but my new book, The Three Mothers, is about Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin, and Louise Little, the mothers of Martin Luther King Jr., James Baldwin, and Malcolm X. I mention these moments now to simply say this work is personal for me. I am tired of Black women being hidden, I am tired of us not being recognized, I am tired of being erased. In this book, I have tried my best to change this for three women in history whose spotlight is long overdue, because the erasure of them is an erasure of all of us. Denying a person recognition is not only frustrating and hurtful, it is violent because it denies their existence, their power, their imprint on the world. It claims it is okay to treat them as less than, as unworthy of being seen, as not needing protection, love, or respect.

The crucial contributions Alberta, Berdis, and Louise made to their families have been ignored for decades and were largely unappreciated while they were alive. They were not given the credit they deserved for the ways in which they fought for their families and the ways in which their love allowed not only for their survival but for the progression of Black freedom at a national and even international level.

Such erasure made writing this book a difficult feat. Finding many of these details was like finding a needle in a haystack. Stories of their lives were scattered mostly in margins and footnotes because very few cared to document anything about these women. I have done my best to piece together their stories while regretting that there is so much more that we may never know about their incredible existence. Just as I was able to build on the little that was out there, I hope others will build on this as well.

What is most revelatory in the lives of these three women was their ability to push against, break down, and step over each and every challenge that came their way. They saw themselves and their children as being worthy of life, worthy of rights, and worthy of grace. Through this radical acknowledgment of their own selves, they survived, and they joined Black American women around the country who contributed to the strides and accomplishments of their larger community.

Denying a person recognition is not only frustrating and hurtful, it is violent because it denies their existence, their power, their imprint on the world.Simply believing they were entitled to the right to live, despite what they were told from the moment they were born, they gave of themselves to a larger movement for Black freedom. I believe this gift they granted all of us was not something that happened unintentionally. Instead, it is evident that Alberta, Berdis, and Louise provided guidance and strategies to fight and survive, at least for their own children. Alongside the other Black women of the twentieth century, both famous and unknown, they believed not only in their own lives but in ours as well.

Alberta, Berdis, and Louise defined for themselves what it meant to be women, to be Black women, and to be Black mothers. In doing so, they opened possibilities of self-definition for their children and the people their children would touch. Alberta found her identity as a Black woman in a more conservative role; she had a strong presence, but she was content with staying in the background of her husband and her children. Alberta was stern yet quiet and soft-spoken. She emphasized the importance of her children working hard and following their paths with dignified discipline. Louise cared deeply about speaking her truth and doing so loudly. She fought against traditional notions of what was expected of her as a Black woman. She traveled on her own when she was only a teenager, she was a proud activist, she was unafraid to disagree with her husband, and she was not intimidated by threats of direct violence or by state officials. Berdis cared deeply about fostering her own creativity and that of her children. She encouraged them to follow what they loved, even putting herself in the path of her husband’s rage to allow this. It may seem that Berdis kept her head lower than Louise, but she too was very capable of being on her own, traveling as a teenager as well, supporting herself as a single mother, first of one and later of nine.

While all three women showed immense strength and in many ways could be described as “the strong Black woman” who did not need others to support them, when we look at their lives more deeply we see their willingness to express vulnerability. Black feminists have discussed the dangers of the strong Black woman stereotype for years, pointing to the problems that arise when everyone else assumes that Black women can somehow sustain more pain, that Black women must be tough no matter what struggles come our way, that it is on us to be the backbone of our families and our larger communities. For many, this trope has become a source of pride, and they are happy to wear the badge of honor, putting everyone else’s needs ahead of their own. However, the lives of Alberta, Berdis, and Louise display a balance between unparalleled strength and an acceptance of their own fragility, and therefore their humanity.

Their self-perceptions and abilities translated into their unbelievable capacity to maintain their hope and their faith no matter what was thrown in their way. They continued to pursue opportunity, they continued to see worth in their own existence at all costs even through their unspeakable losses. When they lost their sons, they chose to continue living; when Berdis and Louise lost their husbands, they were determined to keep pushing and provide as much as they could for their children. Whenever tragedy struck or another challenge presented itself, each of them mourned yet persisted in their pursuit of life.

All three women also sought support. Alberta, Berdis, and Louise formed communities around themselves and their families. Alberta continued what her parents built by highlighting the importance of her church community. She always played an active role in the affairs of the church and became a sister and mother to many far beyond her biological family. Louise found community among other activists when she first moved to Canada. She continued to find community in each place that she and her husband moved to and especially relied on a close group of friends after losing Earl. One couple even took care of some of her children when Louise was institutionalized. Berdis also found community in her church when she was far away from the Eastern Shore and unable to afford visits home. Later in her life, she reconnected with her family members and embraced all of her children’s partners and friends, providing a space for their community of artists and activists in her home. All three women were capable of being fully independent, yet they sustained themselves by depending on connection with others.

The lives of Alberta, Berdis, and Louise display a balance between unparalleled strength and an acceptance of their own fragility, and therefore their humanity.Although it seems that none of the three women cared deeply about formal recognition whether within their families or outside of their homes, each was intentional in passing on her views to her children. All three were aware of the need to share what they’d gained over the years. They did not write books or keep a close record of their own lives, but they cared more about passing on their lessons to their children and grandchildren directly. Even though Berdis never published her writing, she gifted her family members with letters filled with lessons on how to live. Louise was not presented with the same opportunity as her husband to speak in front of audiences, yet she held class in her kitchen for her children on a daily basis. Out of the three, Alberta had the most opportunity for public exposure, but she was still known as the “quiet one,” who preferred to gift her knowledge through her closer connections with her children at home and her students.

Alberta’s, Berdis’s, and Louise’s lives, legacies, and lessons are crucial for all Black women, especially today. Black women and Black mothers continue to face blockades in our pursuit of dignity for ourselves and our children, as well as challenges in our desire to be treated as human beings with basic needs. While the faces and forms of oppression have changed, even if only slightly at times, Black women today rely on the knowledge of those who came before us to continue to survive, thrive, and create new realities.

It becomes especially clear how Black women are being hurt by institutional discrimination when we focus on the current Black maternal health crisis. Black women suffer disproportionate maternal mortality rates. They experience some of the highest rates of death associated with pregnancy and childbirth. They are three to four times more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than white women, and these facts span income and education levels. The National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy points to various factors contributing to this terrifying disparity, showing how it stems from the marginalization of Black women. They state that “maternal health care operates in systems that inherently undervalue Black lives.” Black women are more likely to be uninsured, exposed to environmental risks, receive subpar medical care, and experience racial bias from health-care providers that allow them to be ignored or dismissed by doctors and nurses.

If Black women are able to survive the dangers associated with pregnancy and childbirth, they and their children are still forced to endure the constant threat of violence. Black women and girls are victims of overpolicing, brutality, and sexual harassment far more often than their white counterparts.

Alberta, Berdis, and Louise offer guidance for our modern struggles as Black women and Black mothers. Knowing their stories, acknowledging their humanity, and recognizing their existence allow us to apply their strategies of survival and creation in our own lives. Beyond the personal healing each of us can gain from their inspiring journeys, they also carry guidance for activism, education, and policy. It is in the recognition of Black women’s unique stories that the entire nation can find a path forward that is inclusive and beneficial for all its citizens.

The lessons of Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin, and Louise Little have never been more important for us to observe and hold on to than right now. They offer us, Black women, a refuge that confirms our own existence and a manual on different ways to fight, different ways to survive, and different ways to re-create our world. They offer our nation a political agenda with the lives of the most marginalized at the forefront. They show how policies that would have made their lives easier, that would have protected and supported them, are still needed today. Because of this, they hold the key to many of the political debates and cycles of oppression paralyzing the United States.

It is in the recognition of Black women’s unique stories that the entire nation can find a path forward that is inclusive and beneficial for all its citizens.Alberta, Berdis, and Louise teach their modern readers that there is no single way to be a Black woman and no single way to be a Black mother. In their lives we find validation for the many different ways in which Black women choose to live and to bring life into this world. Through their uniqueness, they directly challenged assumptions, stereotypes, and categorizations that aimed to objectify and reduce them, and studying their lives gives us the gift of doing the same for ourselves today. These different approaches to Black womanhood contribute to the larger fight for our shared liberation.

Alberta, Berdis, and Louise teach us the importance of passing our unique gifts on to others. They all practiced some way of sharing their stories that allowed this book to be possible. Louise practiced the tradition of oral history, sharing her truth with her children and grandchildren. Berdis left her mark through her letters that traveled across the country and the world, following her descendants. Alberta made an imprint through fostering other people ’s talents, and her tutees would remember her anytime they sang or played their instruments. All three women have lived far beyond their time on this earth. With this in mind, we must do a better job of recording our stories and sharing our truths, not only with our immediate networks but with as many people as possible. It is only a disservice when we hide ourselves, when our children do not know what we have gone through and how we survived it, when we allow others to define who we are.

Written records of our contributions are crucial for sustained community strength and shared knowledge. The stories of Alberta, Berdis, and Louise can bring us new breath: by learning the lessons they offered us, even long before they became literal mothers, we can continue to find meaning in our own struggles and accomplishments. These three women bring me incredible inspiration and hope; through honoring their existence and worth, I have affirmed my own.

Yet their lives speak to more than what we, Black women, can gain from their stories in order to persist in our own journeys; they speak also to the role of the communities and society we find ourselves in. Their stories are not only about how as Black women we can protect ourselves and our families but also about how others, including our loved ones and even policy makers, can and should protect us. While it is true that Alberta, Berdis, and Louise lived powerful and influential lives despite a lack of additional support, we should not accept the challenges they faced as if they were unavoidable. Such challenges have hurt and even killed far too many of us. We should instead honor their journeys and use them as guidance for making life easier for all Black women and mothers moving forward.

*

At the heart of this writing is the constant tug-of-war we Black women face and our best attempts to find balance despite this. We are deemed “less than” when we are forced to be “more than.” We are reminded over and over again that we are viewed and treated as objects without needs for dignity or protection, that we are less intelligent, less beautiful, less able; and as a result, we push ourselves to always be more, working harder than those around us to pursue our goals.

Their stories are not only about how as Black women we can protect ourselves and our families but also about how others, including our loved ones and even policy makers, can and should protect us.This balancing act of being told the opposite of what we know about ourselves and acting with such a dichotomy in mind leads to our ability to produce life even when it is denied us. Our lives consist of fighting for ourselves and our communities in response to the attacks we face, pushing against the sources that deny our existence.

Black motherhood, in and of itself, is liberating and empowering; it is the lack of support we need that can make the experience oppressive and draining. Being a Black mother should not be seen as a journey one embarks on and endures on her own. Friends and partners, when they are present, should share in carrying the load Black mothers hold on their shoulders. Rather than standing in awe of Black mothers and simply commenting with deference on their incredible strength, others should stand with them and lighten their burden. Partners should participate equally in the home and in supporting Black mothers with their own dreams. Public officials should listen to what Black mothers say they and their community members need. It is time for the honor many quietly pay to Black mothers to become as loud as Alberta’s choir, as consistent as Berdis’s love, as strong as Louise’s fight.

__________________________________

From The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation by Anna Malaika Tubbs. Used with the permission of Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2021 by Anna Malaika Tubbs.