Remembering the Birth of Gabo on the Birthday of Gabriel García Márquez

Literature and Journalism Were Never the Same After One Hundred Years of Solitude

Gabo Is Adjective, Substantive, Verb

In which García Márquez is transformed into the famous author of One Hundred Years of Solitude

*

Ramón Illán Bacca: There’s gabolatría on the part of critics, commentators, journalists, and they create a crushing, definitely overwhelming presence. Especially for those of us who came later and were trying to write. Everybody aspired to writing the other novel that would define an epoch. I even recall that in the novel of Aguilera Garramuño—A Brief History of Everything, it was called—there was a strip of paper, a sticker, that said: “The Successor to One Hundred Years of Solitude.” Everything was sold like that. Ay! the ravages of garcíamarquismo.

José Salgar: I believe he influences everything. He had a bad influence on the generation immediately following his. Something similar to what happened with Watergate. After Watergate all the professional journalists felt obliged to bring down their presidents. When Gabo had the great success of the Latin American literary boom, all the journalists believed they were obliged to write better than he did in order to succeed. And many of them thought Gabo was a poor writer and that they wrote better and they began to imitate him.

RIB: I remember Juan Gossaín, a journalist who acquired a good deal of prestige writing like García Márquez. It was very clear that he garcíamárquezed all the time.

Quique Scopell: I remember one day in Kid Cepeda’s house when Gabito told Gossaín to stop imitating him.

JS: It’s a normal development. I lose the thread with Gabo and he begins to make his own character different, but he quickly returns to Colombia. He never lost the connection to journalism except for those five years. Until we all suddenly convinced him, especially Guillermo Cano, to write his columns. He began with one about a brilliant minister; he wrote from wherever he was, and he sent it in on time, but now he was a different Gabo.

RIB: Then came the overflow about him. at’s when he becomes Gabriel García Márquez. And it’s when everyone is trying to know things about the man, right? There were even gabolaters. Gabolatry began, which still exists, of course. Universally. Here there were people like Carlos Jota who was involved in gabolatry, he began to write down facts about García Márquez, to collate things; if he was here, if he was there. It was a little later, when Jacques Gilard, the Frenchman, arrived . . .

Miguel Falquez-Certain: Jacques Gilard arrived in Colombia maybe in 1977. When he arrived, he communicated immediately with Álvaro Medina, since he already knew about him from references, and he helped him find all the necessary research materials to write his doctoral thesis on García Márquez and his friends from La Cueva, whom Gilard would later baptize the Barranquilla Group.

It’s a completely regional novel. Nothing’s imagined.

RIB: That’s when I become involved in the complicated story. I come back from the interior, I return to the coast, and then I hear things about him, I meet Jaime García Márquez, his brother, yes, but I wasn’t one of the gabolaters. I didn’t have much interest in looking for information.

Fernando Restrepo: When I return to Colombia, the figure of Gabo always appears among us, and the first thing we did when I came back was to produce In Evil Hour for television. And that’s when Gabo’s real interest in visual media is born. We began to talk a lot, a great, great deal, about the possibilities of his plots being transferred to television. In Evil Hour was the first work by Gabo brought to television, to the screen.

RIB: Well, every great author really arouses a great deal of interest, not only in his work but in his person. What hasn’t been written about Thomas Mann? The other day I read a very long biography.

Even in minor authors, a great deal of interest is suddenly awakened.

For example, there’s a character who attracts my attention, that is, Somerset Maugham, and I, for example, read almost all the pieces I see about Somerset Maugham. If you do that for a minor author, how will it be for the authors whose presence is so imposing?

Nereo López: He wasn’t made in Colombia. He lived in Paris and in Mexico City but Colombia . . .

FR: I come back to Bogotá in ’68 from Europe. So I encounter the presence of Gabo everywhere.

QS: I assure you that if you ask one of those types from the capital, they won’t understand half the novel. They don’t understand it because it’s a regional novel about Barranquilla, about the coast. Because Colombia has three regions: the Paisa region; the Cachaco region around the capital; and ours, the region of the ignoramuses to them. That book, half of the Cachacos don’t understand it because they can’t imagine that a man would do the things the novel says. It’s a completely regional novel. Nothing’s imagined.

Santiago Mutis: That’s a world lived by him, which I don’t have. I’m from the city. I have a family life that’s totally different. My education was different.

Eduardo Márceles Daconte: It’s difficult. Not only for a person from Aracataca but for any writer. What Gabo marked out in literature is a very high point, so one often feels . . . What shall I say? He’s a figure that somehow has weight within the literary trajectory, not only of the coast but of Colombia. Of course, of the world too, but let’s at least leave him there. So it’s a very high fee we writers from that region paid, but filled with admiration in any event.

Before One Hundred Years he was a common, ordinary person, and after One Hundred Years he began to be another person.

SM: Gabo has traversed almost all of my life. The first books I read were by Gabo, and Gabo still continues to be an important influence; so the relationship with him has been real. For any person of my generation who has written it is permanent, because ever since he began to read until he became a man, until he became a writer, Gabo is there. One cannot deny that. He is a tremendous presence. But it’s also very different, let’s say, to reread him now than when one read him as a boy. As a boy, Leaf Storm or The Colonel is the truth. What an intense way of approaching life and literature! From then on you began to make your own way. The only thing that’s an influence is that one attempts to have the same intensity with things, but with one’s own things. at’s the lesson. His intensity. How much one can demand of oneself. But with things that are one’s own. And each person has his own.

Rose Styron: Bill had met Gabo with Carlos Fuentes in Mexico City. At a very, very large party where they both were, but I didn’t have the chance to meet him and talk to him until ’74. I really didn’t know that he was going to be there. I had been in Chile at the time of the coup and returned early in ’74. I think this was later in the year, in ’74. It may have been in ’75. It was during one of Bertrand Russell’s tribunals and a conference of some prominent Chileans who had been imprisoned by Pinochet had finally gotten out: singers and diplomats, all kinds of people. The tribunal brought them to Mexico. So I flew to Mexico City to meet Orlando Letelier, who had just arrived, not knowing that Carlos and García Márquez would be there too. We were all activists at the time, and we were all anti-Pinochet. We had all been involved the previous year in the Chilean fiasco. So that’s how we happened to meet, and then the three of us became very good friends, and since then we’ve spent a good deal of time together.

QS: Besides, a person who had his beginnings, so humble . . . As I’ve said, for me that’s no sin or offense. On the contrary. He’s a tenacious guy. Honest. Because he’s been honest his whole life. A working man. Persistent in his work. What else can you ask of a man? One can be furious with him as a person.

Not as a literary man, but as a person. He deserves it. That place he has in life, he’s worked it.

Emmanuel Carballo: There are two García Márquezes: before One Hundred Years he was a common, ordinary person, and after One Hundred Years he began to be another person . . .

Translated by Edith Grossman.

*

NEW YORK: Join Silvana Paternostro and Álvaro Enrigue tonight at McNally Jackson for a conversation on García Márquez’s legacy on his 92nd birthday.

__________________________________

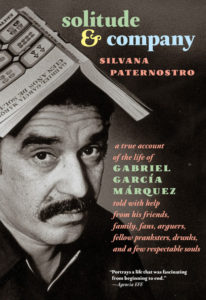

Excerpted from Silvana Paternostro’s new book Solitude & Company: A true account of the life of Gabriel Garcia Marquez told with help from his friends, family, fans, arguers, fellow pranksters, drunks, and a few respectable souls, published today by Seven Stories Press.

Silvana Paternostro

Silvana Paternostro has written extensively on Cuba and Central and South America as well as on women's issues, AIDS, revolutionary movements, underground economies, and the intersection of culture with politics and economics. Her book In the Land of God and Man: Confronting Our Sexual Culture was nominated for the PEN/Martha Abrams Award for First Nonfiction. She is also the author of My Colombian War: A Journey Through the Country I Left Behind. In 1999 she was selected by Time/CNN as one of 50 Latin American Leaders for the New Millennium. She was also associate producer on Che: The Argentine and Che: Guerrilla, a two-part movie based on the life of Che Guevara, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2008. Silvana lives in New York.