Yesterday, I took a photograph of abandoned plastic sleds in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. The photograph’s blue shadows match the pullover Mark Baumer (1983-2017) wears in one of my favorite photographs of him. In it, he’s protesting Textron, an industrial conglomerate based in Providence, Rhode Island whose manufactured cluster bombs were used to kill civilians in Yemen in 2016. DEAR TEXTRON, Mark’s epistolary protest sign reads. STOP KILLING CIVILIANS / MAKING CLUSTER BOMBS / PROFITING OFF DEATH. Seated on the ground in nonviolent protest, Mark obstructs Textron’s front door while two other activists chain their necks to two additional entrances. Just after this photograph was taken, all three activists were arrested.

*

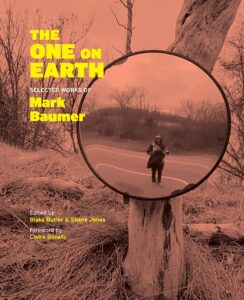

Tomorrow, December 19, 2020, is Mark’s 37th birthday. I’ll spend some of it writing the foreword to The One on Earth: The Selected Works of Mark Baumer, for which part of my research has included reading “Unconscious Processes in Relation to the Environmental Crisis,” by the late psychoanalyst Harold F. Searles. This article, written in 1972, feels contemporary as I reflect on Mark’s activism and how the violences we inflict upon earth affect how we treat one another—“how we take and push and mine and drill into one another” per Winter Count, a multi-disciplinary art collective whose work “engages with land and water under current threat by extractive industry.” Mark’s activism burgeoned when he learned about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: by understanding discarded plastic’s dangers, Mark began to recognize the interconnections between human and non-human life. Plastic is the greatest threat to the ocean; 80 percent of marine litter comes from the land. These statistics beg questions: Where do blue sleds go when they die? Do we go there too? And, in our dying, what do we lose?

Searles: “A technology-dominated, overpopulated world has brought with it so reduced a capacity in us to cope with the losses a life must bring with it to be a truly human life that we become increasingly drawn into polluting our planet sufficiently to ensure that we shall have essentially nothing to lose in our eventual dying.”

Or, as Mark writes:

We might all have the same brain. Unfortunately, I think the brain is dying. Literally, everything we touch is death. The water is going to kill the brain. The food is going to kill the brain. The walls are going to kill the brain. The society is going to kill the brain. The air is going to kill the brain. The stress of brain death is going to kill the brain. The only solution is nothing. Humans have done nothing but create brain death and any time we try to correct our mistakes we create more brain death. The brain will die. Somehow we must accept life after the brain or we must accept earth post brain. This is a little sad, but brains were never constructed to outlive earth. Even though I am not sure if I can live without a brain I’m pretty sure earth will continue without the brain. When my brain dies hopefully I will remember to walk out into the forest and sit down in the pine needles if there are still pine needles out in the forest.

In October 2016, Mark left his home in Providence, Rhode Island for a barefoot walk across the country. He called this feat “Barefoot Across America.” The purpose of his walk was to raise awareness regarding climate change, and to crowdsource $10,000 for the FANG (Fighting Against Natural Gas) Collective, with whom he protested against Textron. Walking from the East to the West coast was something Mark had already accomplished in 2010, when he walked for 81 days from Tybee Island, Georgia to Santa Monica, California while wearing sneakers and pushing his possessions in a baby carriage. His writing from that walk was self-published in I Am a Road, excerpts from which are included in this volume.

In October 2016, Mark left his home in Providence, Rhode Island for a barefoot walk across the country. He called this feat “Barefoot Across America.”After reading Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run, Mark began training to run barefoot. He chronicled his barefoot runs in YouTube videos—The New Yorker’s Anna Heyward refers to Mark as a “compulsive social media diarist”—and, after beginning his barefoot walk, began producing one video everyday, as well as text-adorned photography, poetry, and aphoristic journal entries, archived online at barefootacrossamerica.com. Mark’s travel writing and multimedia gestures read like a cross between Thich Nhat Hanh, Miranda July, Bas Jan Ader, Simone Weil, Pee-Wee Herman, Andy Kaufman, Greta Thunberg, and the magical fourth-grade nephew you never had, clad in a cardboard costume of a house set on fire, screaming at adults during a climate march.

On the 64th day of his walk, Mark took a bus from Zanesville, Ohio to Jacksonville, Florida. Icy weather in Ohio had created impossible walking conditions, as Heyward writes, “not because of the snow but because the calcium-chloride de-icing salts that were sprinkled on the concrete cut [Mark’s] feet.” He arrived in Florida late on the evening of December 17, 2017. “I woke up in the state of Florida near a giant wall,” he wrote on the morning after his arrival. “It was painted with fish. The sidewalk was warm. I looked up at the sun and smiled. It was toasting my face.”

During his last month on earth, Mark approached Barefoot Across America with renewed vigor. On Day 77, he stayed at the Sacred Water Camp in Suwannee Springs, Florida, where he participated in a protest with water protectors against the Sabal Trail Pipeline, which decimated orange orchards and former conservation land (sold to the Sabal Transmission Company for several million dollars). On Day 82, Mark’s friend Matt drove three hours to Madison, Florida, just to give him a hug. “I’m pretty sure if a friend randomly shows up in the middle of Florida to give you a hug then you are required to finish whatever journey you are on,” Mark reflected. On Days 88 and 94, Mark was profiled in the Tallahassee Democrat and the Jackson County Floridian, respectively.

At 1:15pm on January 21, 2017, Mark was struck and killed by the driver of an SUV while walking westward along the south shoulder of Highway 90 in Walton County, Florida. It was the 101st day of Mark’s journey, and it also happened to be the afternoon of the 2017 Women’s March, just one day after Donald Trump’s inauguration. Abiding by safety conventions, Mark wore a fluorescent orange vest and walked against traffic. In a police report, the SUV’s driver, who was traveling eastbound when she veered out of her lane, said she saw Mark before she hit him. He had walked more than 700 miles and was 33 years old.

Hours before his death, Mark posted a photograph to his blog. In it, his bare toes are framed below the word KILLED, spray painted in yellow atop the highway’s asphalt. In his blog entry’s accompanying video, Mark points the camera toward this word: KILLED. “The language of capitalism,” he remarks.

“If I die on this trip, it’s not going to be because I didn’t wear shoes,” Mark said in a video on November 26, 2016. “It’s going to be because an automobile kills me.”These days, writing this around the anniversary of Mark’s death, I keep returning to a black-and-white photograph of Dutch performance artist Bas Jan Ader walking on the berm of a highway in Los Angeles, California in 1973. Accompanied by lyrics from The Coaster’s “Searchin”—yeh I’ve been searchin’—the image is at once banal and evocative, and conjures the American fantasy of the highway of freedom and connection: the Beat romanticism of the road; the suburban imaginary of the road; the arteries of capitalist shipping required to fuel Amazon’s corporate death drive; the cross-country trip as coming-of-age rite; the United States’ “this land is my land, this land is your land” nonsense; Bob Dylan’s “let me walk down the highway with my brother in peace” American folk dream; the number of people who died by automobile in 2017; and the delusion of anyone thinking they can walk a mile in someone else’s shoes.

“If I die on this trip, it’s not going to be because I didn’t wear shoes,” Mark said in a video on November 26, 2016. “It’s going to be because an automobile kills me.”

*

Those unfamiliar with Mark may assume his writing lends itself to a deceptively bizarre read. On first encounter, one might think Mark’s work is weird for the sake of being weird, when in fact its weirdness (and sentient weirdening) is entangled with other weirdnesses: the weirdness of linguistically manipulative advertising and propaganda; the weirdness of the human brain’s non-sequiturs; the weirdness of human beings thinking thoughts all the time, ergo we cannot know anyone’s mind; the alienation of daily objects, events, and serendipities that are just a little bit off, and how these objects, events, and serendipities don’t quite belong either in the world or in the realm of language. Not to mention the weirdness of attempting to wield language that bears socioculturally-approved “sense” when lived experience is myriad, ineffable, synesthetic, senseless.

Mark’s shorter prose pieces often read like fables containing moral lessons geared toward CEOs, grown men with anger problems, megalomaniacs, and white supremacists. Critics sometimes describe Mark’s writing as childlike, which feels apt and aligned with our world’s political landscape: children are, after all, leading the global climate movement; and the bulk of our nation’s leaders fail to lead at all because their souls are possessed by unprocessed inner children. Mark was an only child whose writing is full of rage and sadness, but not grief, per se. Rather, his work is often euphoric, seriously playful, ecstatically joyful, egoless: a manic response to the pain of being alive in a world where everything is dying in front of our eyes.

Along with excerpts from his travel journals (I Am a Road and the Barefoot Across America blog), a novella (At Some Point in the Last Nine Billion Years), and “Yachts,” a short story about a penis that abandons its seven-week old infant body to tour South America and study postcolonial theory, The One on Earth contains Mark’s Personal Statements for Brown University’s MFA Literary Arts Program (“Dear Brown, It is important to know that I am not a joke. Instead of doing cocaine I have worked the last two years on my writing. I have started four novels and tossed them away when they were done. I feel like failure is a big part of my writing.”) and the Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University (“It is difficult for me to know what the fall of 2017 will bring. […] Maybe I will have a child at this point or maybe I will begin coaching middle school track”); cover letters addressed to future employers (“Would you be more or less likely to hire me if I told you one of my teeth is probably going to fall out unless I get dental coverage?”); prose miniatures about the Brown University MFA Literary Arts Program; a Tinder bio set in couplets entitled “Not Ted Cruz”; stock tips for unpublished authors trying to get rich; a fairy tale about Jonathan Franzen’s leg falling off; some facts about a self-immolating web content specialist; multi-step writing prompts; and poems rejected from A Public Space, Boston Review, and Beloit Poetry Journal. Apart from my aforementioned genealogy (which included Thich Nhat Hanh, Pee-Wee Herman, &c.), parts of Mark’s writing feel like a Frederick Wiseman documentary narrated by Werner Herzog; parts feel like Daniil Kharms walking around Wal-Mart after midnight; parts feel like Yorgos Lanthimos being commissioned to write a Little Golden Book; and parts feel like Lydia Davis thumbwrestling Donald Barthleme on Vine at TGI Friday’s.

Maybe Mark’s writing is absurd—a word so overused to describe literary (and all, really) art that it’s been neutralized—or maybe what’s actually absurd is the formality and desperation with which we prostrate ourselves before institutions, faux-democratic corporate apps, celebrities, and CEOs, plus all of our big and little addictions: from alcohol and drugs to sex and love, from social media dopamine hits to performance enhanced sports and the ways we “throw [our] money at each other.” Maybe what’s also absurd is that there exist famous writers whose famous books are written on famous computers made by a corporation named after a piece of fruit symbolizing original sin.

And although I can’t find a clear answer online about where these famous computers are grown, I often think about the time Mark stood in the Providence Place Mall’s Apple Store holding a sign that read SILENT HUNGER PROTEST, and also about how the only article Mark ever wrote for his undergraduate college’s newspaper almost got him expelled, so he started a zine called G.M.B.O. That zine was an act of journalism, of revolt—of participation in political community. It was, like the writing in this volume, an act of refusal. And I am thinking now about how refuse can become compost, and how compost can yield fruit, and also of the late poet C.D. Wright, who would have turned 71 today, January 6, 2020. Before her death, C.D. called Mark “an angel sent to earth to protect us.” She also wrote: “We must do something with our time on this small aleatory sphere for motives other than money. Power is not an acceptable surrogate.” The irony and grace of The One on Earth is that it won a prize.

*

As I think of Mark’s oeuvre and plastic detritus, my mind turns toward the great garbage patch of the soul. What if, instead of using the world to destroy ourselves, we responded to political crises by confronting our pain, meeting our shadows, and attending to our anxieties, to the sources of our suffering? James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Although Mark’s walks may be deemed risky as they put him in the line of danger, they were ultimately about aliveness, desire, intimacy with the earth and its elements, and a particular suspension of time.As I write this, I’m supposed to be considering how Mark’s work makes people face truth in a way that feels different from other political commentary. At once, a headline on NPR’s website appears: “U.S. Capitol in Chaos as Pro-Trump Extremists Breach Building.” White supremacist vigilantes—terrorists—are presently storming the US Capitol Building in a combination coup-superspreader event. They’re smashing windows, scaling walls while wearing American flag capes, wandering around the Senate floor in furry costumes, pulling papers from government officials’ desks, waving Confederate flags while chanting “1776.” Further images from the news reports are also rife with hatred: actual, functional gallows; pipe bombs and Molotov cocktails; and clusters of zip ties, presumably to take senators hostage. I study a photograph of a man pointing toward his dick while sitting at Nancy Pelosi’s desk, and a second photograph of a second man smiling and wearing a knit TRUMP cap adorned with a pom-pom while carrying Pelosi’s Speaker of the House podium.

My mind turns toward growing up in rural western Pennsylvania, where I encountered firsthand people who are lied to and brainwashed by rich megalomaniacs who gain from this, and who often hide behind ‘God,’ patriotism, and xenophobic fraternity. All of these forms of false inclusion stoke white rage, and trick people into feeling included while they are robbed. Then I think about Harmony Korine’s Gummo, and of my friends’ parents’ gun cabinets and their ancestors’ gun cabinets, and their ancestors’ ancestors’ gun cabinets. And then I remember this moment from Mark’s 37th day on the road in central Pennsylvania:

Halfway down the mountain I heard gun shots. At first I thought I was being shot at. The gun shots continued. A few hundred feet away I saw children playing in the yard.

14,000+ people were arrested during the Black Lives Matter protests following George Floyd’s death. As of my writing this, 13 white terrorists who participated in the Capitol insurrection have been arrested.

*

As the above events unfold, I reread a piece by Mark called “White people in blackface wearing kkk hoods under their hijabs while riding motorcycles.” This afternoon, it feels prescient, and like a prose capsule containing Mark’s rage at what people who look like him do, and fail to do. The text enacts a sort of Jenga’s ladder of whiteness, and points to white solipsism, wherein whiteness cannot see past itself, and paints everything white in its absence, and cannot serve to protect anything but itself:

After work, a white man named “Doug” liked to read magazines while eating pizza. Sometimes Doug read a magazine that talked about how all the dead white people in America got killed by other white people who would eventually get killed by even more white people. Doug was scared. He only worked with white people. Doug decided to wear a motorcycle helmet to work because he thought it would make him safe.

As a reader, I appreciate how “Doug” exists in quotation marks like an ontological curiosity—“who” “is” “Doug” “and” “why” “is” he” “so” “fucking” “afraid”?—and that the magazines “Doug” reads are unnamed. Like whiteness, I imagine these magazines are blank inside: sites of projection upon projection upon projection. Because “Doug” cannot tolerate his mind, “Doug” is scared.

In general, Mark aimed to comport himself as the opposite of “Doug,” not out of self-righteousness but rather with the optimism that others would follow suit. Doug is complacent and afraid, whereas Mark refused to turn away from fear. He did not flee his shadows: I think of the many videos in which he records his own shadow moving through space, or where a cell phone’s shadow cascades across his face. And he continuously worked on himself and analyzed his own mind—with which the health of the heart, after all, is intertwined. In particular, Mark’s walks across the country demonstrate his psychic aptitude for tolerating his own mind, confronting fear, and taking risks. “‘To risk one’s life’ is among the most beautiful expressions in our language,” Anne Dufourmantelle writes in In Praise of Risk, a book in which risk is defined as a decisive instinct, the opposite of complacency. “Risk […] opens an unknown space,” Dufourmantelle expounds. “How is it possible, as a living being, to think risk in terms of life rather than death? […] What if [risk] supposed a certain manner of being in the world, constructed by a horizon line?”

Although Mark’s walks may be deemed risky insofar as they put him in the line of danger, they were ultimately about aliveness, desire, intimacy with the earth and its elements, and a particular suspension of time. While his videos are numerically demarcated by days—Day 98, Day 99, Day 100—his walk was a continuous meditation, a poem written with two feet, and a path leading toward a utopia where, to quote his final entry, “one day everyone will be able to walk down the middle of the road free from all the violence this society has built.” Beyond his documentation of walking across America, so many of Mark’s videos—for example, his instructional videos (e.g., “How to be a poem writer”) and hilariously destabilizing phone calls to literary agents (“Hey, hello Claudia Ballard, this is Mark Baumer. […] You wouldn’t believe this, but I’m interested in joining the ranks of many published authors who think they’re going to become famous but actually just have middling success and eventually they become so discouraged that the written word is no longer an enjoyment for them”)—are about critically interrogating the comfort of privilege, and of unsettling people who feel complacently settled in who they think they are.

As someone deeply invested in practices that spelunk and sweep the unconscious—psychoanalysis, dream journaling, Zen meditation—I’m especially interested in Mark’s freely associative video diaries and journal entries, and his emphasis on unbridled language-making across media.

His language is alive; it is thinking his brain; it is his thinking-brain. He is speaking to the camera; he does not know what he is going to say; sometimes his eyes widen; sometimes he begins to cry; he lets us see him cry. On December 5, 2016, Mark is alone in a hotel room in Ohio, and he is grieving. He has just received the news that his friend, Nick Gomez-Hall, whom he was supposed to meet in California at the end of his trip, and with whom he had plans to go bowling, has died in the Oakland Ghost Ship Fire. Nick had been missing for one day. “I saw on the news that my friend Nick was officially one of the people who died in the Oakland fire,” Mark says. “Nick, I love you. I miss you. And it hurts that you’re gone.” On his blog, he writes: “Maybe the saddest and most beautiful thing about all this is the fact that the last message Nick sent me was, ‘I love you Mark.’”

There is pain in Mark’s speech, and in his writing, and this pain brings him—and we, his travel companions—closer to truth. And, like America, the unconscious wants truth. It needs it. Mark knew this: that only via truth will we continue to dream in hell.

*

missing

I don’t want / to look / at the last email / you wrote / because / I still hope / somehow / you will / someday / float / another one / into my bucket / once / you said / I want to create / vulnerable statements / that / connect with strangers / it hurts / to think / right now / but / I still / remember / the time / you asked / if I was / going through / the desert / because / you were / in the desert / and / maybe / we could both / be / in the desert / but / I never / made it / to the desert / before / you left / the desert

December 4, 2016

*

As a fellow only child who talked with Mark about only-childhood, I’ll now offer some thoughts which are only partially about only-childhood. “I wish I had written a book about the empty space where my brother was supposed to exist,” Mark wrote in the books keep getting worse and worse. Are only children gifted with a particular empty space, a lack from which they love? Mark was tall and vegan and straightedge—not because he was an only child—and a loyal, responsive friend who remembered other people’s birthdays, participated in numerous communities, and was talented at organically forming communities wherever he went. This was probably because he was an only child, and probably too because he was Mark, and also because he was a hard-worker who paid attention to details, who also happened to be exceptional at using the Internet. I especially loved emailing with Mark. He once sent me a Spartacus workout. And during his barefoot walk, we had a virtual dinner party. This was before COVID-19 made that a thing. He was staying in an Airbnb in Ohio, and I remember him eating a can of chickpeas.

Although the images of his feet posted to Instagram may suggest otherwise, Mark took care of his body and meditated daily and therefore did not exist at a distance from his mind. Maybe the blisters on his feet were extra eyes—the better with which to attend to the world’s pain, of which there is so much that the road glistens. His commitment to self-care helped him tend to others. For example, once, when I was giving a reading in Providence, Mark brought me a lemon: I was traveling and always drink lemon water in the morning, and I did not have a lemon with me. Mark somehow knew this. Today, whenever someone gives me a piece of fruit, I think of Mark. Searching my inbox for our correspondence, I realized I did not respond to an email from Mark sent on December 10, 2013 concerning the work of an author named Lee Paige. That email links to a 404 File Not Found page at BOMB. “I don’t know if you’ve heard of Lee Paige, but he went to the same MFA we did at the same time we did,” Mark wrote. “Pretty good writer.” Was Mark Lee Paige? I don’t know for sure, because I failed to respond. Mark always responded to emails; I wish I had written back.

*

On December 29, 2020, I received a card from Mark’s mom, Mary. She has been taking walks on the beach. My new thing is to pick up trash that is plastic on the beach, she writes. Every single time I walk the beach …

*

How much should your foreword emphasize Mark’s being gone, my friend Ian Hatcher, who also attended Brown’s MFA with Mark, asks me. As Ian talks, I type a list that may or may not be a poem:

50 novels—unreadable

The simplicity of a single person doing a thing

Walking across the country: impossibly large

Impossibility of holding all of it in the mind

“Rendering the impossible possible as work”

We live in a really dark children’s book

Mark knew this

His practice embodies the desire to begin again,

enacting a magic

Even if Mark had made it all the way across the

country, there would still be climate change

Jacques Derrida: “Such a caring for death, an awakening that keeps vigil over death, a conscience that looks death in the face, is another name for freedom.” Mark is still alive in the moment of a reader reading his work; The One on Earth is a living document.

*

TEN NOTES I TOOK WHILE WRITING THIS INTRODUCTION

1.

Ryan LaMothe: “Spaceship earth has already hit the iceberg of climate change, though there are no rescue ships deployed to save us.”

2.

There is a chart in front of me labeled Temperature Anomaly whose squiggle ascends and ascends as years pass

3.

Neoliberal capitalism

4.

As of October 2020, the Trump Administration has covertly signed away over 125 climate change protections

5.

Mark: “For one minute, be optimistic about the global failures of humanity’s lack of concern with their global failures, and then for the rest of your life live inside this optimism as you try to almost convince yourself that there is no need to worry about the continued existence of ”

6.

In a text message, Jess writes: “The one thing that ‘normal’ politicians hate the most is being made to look like weak The entirety of the Senate and House is bound together now in anger and humiliated hatred.”

7.

8.

If this page were a webpage, I would embed Johnnie Frierson’s “Miracles”

9.

…and Minor Threat’s “Straight Edge”

10.

The notes on what Mark made here in his time are endless.

*

In his practices as a writer, performance artist, and activist, Mark attempted to embody a central problem of our time: scale. His writing deals with immense problems, all of which are bound up with climate change: the greed of accumulated wealth and power, corporate evil, systemic injustice, and violence against human and nonhuman life. So too does Mark’s practice embody the impossibility of one person addressing those problems. Yet I trust the impossible is possible. As I write this, there are countless tabs open on my computer documenting Mark’s activism. And I can’t stop being haunted by a photograph from August 2018 in which Greta Thunberg wears a blue hoodie the color of Mark’s pullover during the Textron protest. It is the color of the abandoned sled and sky in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, and the color of the ocean sans man-made pollutants.

The introduction can end with infinity, I write in my notes. Because Mark’s work has to do with infinity: how we’re infinitely fucked, unbounded and complicit at the end of a world punctuated by Starbucks, Walmart, Taco Bell, KFC, Pizza Hut, and Wendy’s. “A cow looks at itself and thinks, ‘Oh well,’” Mark writes. Because despite there being no end to this world’s predictably boring evil, we’re together, whether we acknowledge it or not, and whether we like it or not—and not just with one another, but with the world itself. In 1927, Romain Rolland sent a letter to Sigmund Freud; in it, he referred to a mystical sense of oneness with the external world as the oceanic feeling. Not everyone can turn outward from narcissistic suffering and the ego’s iron grip to feel the world and that oceanic feeling, but Mark did.

Almost 100 years after Freud popularized Rolland’s concept in Civilization and Its Discontents, Mark narrates the oceanic feeling in I Am a Road:

I began to cry. The ocean just looked at me and shrugged as I limped towards it. When I reached the sand, my body no longer hurt because it was no longer required to be the body I had required myself to be. The spacesuit I had worn the entire trip was soiled with every mile I had traveled. I removed these stains and placed them in the body I had required myself to be. The spacesuit I had worn the entire trip was soiled with every mile I had traveled. I removed these stains and placed them in a trash barrel. Tears continued to leak from my brain. I no longer had to pretend I wasn’t human. The ocean barely acknowledged me as I stepped into it. I didn’t know what else to do so I just floated.

Walking across the country barefoot; walking across the country in shoes; hitchhiking across the country with a traveling companion; attempting to hitchhike from Providence, Rhode Island to Los Angeles, California for the annual AWP Conference; engaging in labor negotiations at work, winning contract negotiations, and becoming a union steward; publishing 50 novels in a year; eating pizza everyday for three months; teaching a creative writing workshop dedicated to “the art of subtle weirdness” with classes dedicated to attending other classes, writing failed novels, sharing silence, yelling, and celebrating everyone’s birthday; writing for eight hours a day. It is an insurmountable task, to introduce Mark Baumer, to scale down his oeuvre. I have no doubt he would have appreciated the task’s absurdity. And I have faith this is the first of many edited anthologies of his writing and cross-media artwork to come.

________________________________________________

Excerpted from The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer, edited by Blake Butler and Shane Jones, foreword by Claire Donato. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Fence Portal. Copyright © 2021 by Claire Donato.