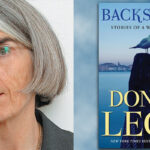

Remembering Alice Mayhew, Legendary Editor

Samuel Freedman on Working With One of the Greats

On a bookshelf alongside the dining-room table, I maintain a narcissistic shrine consisting of first-edition copies of my eight books. Four of them were published by Alice Mayhew, the legendary editor at Simon & Schuster who died earlier this week at the well-disguised age of 87. And those four volumes are the ones that Alice herself presented me, each fresh from the bindery, and each containing a personal note.

Over my quarter-century tenure with Alice, which ended in 2018, her congratulatory notes grew gradually more expansive, a sign of our deepening literary partnership. Tucked inside the cover of our final collaboration—Breaking the Line, which was about black college football and the Civil Rights Movement—she inscribed a note card this way:

“I am particularly proud to publish this book. It is brilliant and it adds to the world’s moral content. That is rare and thrilling.”

Those words say so much more about Alice than about me. You see, I was not one of the many stars in her firmament, the authors like Woodward and Bernstein, Doris Kearns Goodwin, David Maraniss, Taylor Branch, and Diane McWhorter, whose names deservedly adorn Alice’s obituaries. I never wrote the kind of Washington-politics books for which Alice is famous, indeed that she in some respects created.

But as the midlist author of a luminous editor, I can attest with a special credibility to Alice’s greatness—her ferocious intellect, tenacious devotion to her authors, attention to every kind of detail in the editorial process. The persistent critique of Alice was that she only cared about her best-selling, celebrity authors. As for the rest of her roster, supposedly she handed off their editing to her young assistants. Allegedly, she did not even read many of the books she published.

From my own experience, such a portrait of Alice completely distorts, maligns, and misrepresents her. Although several of my books for Alice won or were finalists for major awards, they cumulatively lost Simon & Schuster several hundred thousand dollars. Following my own peripatetic vision, I bounced from topic to topic, from political history to religion to sports and race.

Never once did Alice mention the commercial outcome of any book of mine; never once did she try to steer my ambitions onto some purportedly safer subject matter. In fact, the book of mine that we both thought might finally earn me a breakthrough readership was the one that received the most equivocal reviews and the poorest sales.

For Alice, of course, that world was publishing, and her record of excellence is self-evident, from Our Bodies, Our Selves through All the President’s Men to Parting the Waters and No Ordinary Time.Yet that book—Who She Was, about my mother’s upbringing in the Bronx during the Depression and World War II—was the one that Alice most viscerally embraced. Now that I have read the obituaries that fill in many gaps about her life, I can understand why. Alice was born in 1932, just eight years after my mother, and like her grew up in the struggling Bronx, pushing against the boundaries imposed by gender roles and traditional religion to burst into the wider world.

For Alice, of course, that world was publishing, and her record of excellence is self-evident, from Our Bodies, Our Selves through All the President’s Men to Parting the Waters and No Ordinary Time. When Alice first signed me up in 1993 for the book project that would become The Inheritance, a chronicle of how three working-class families evolved from New Deal Democrats to Reagan Republicans, I felt that the hand of heaven itself had plucked me to sit among the angels.

Instead, during my first lunch with Alice, I squirmed in my seat trying to keep up with the gusher that was her brain. Brusque, brilliant, profane, Alice could assay expertly on theater, opera, presidents, religion, higher education, and, of course, industry gossip. She was a jock, too, who started many days with a personal trainer and played tennis virtually her entire adult life. Her athleticism added to the coiled, taut, explosive quality of her presence.

When I am working on a book, I withdraw into it, easily going years without feeling any inclination to speak to an editor. With Alice, I discovered how much of her editing involved luring me out to lunches every three or six months—invariably at her favorite place, Michael’s, and always at the table reserved for her—and doing the conceptual framing of my book-in-progress.

Once she went to work on the final manuscript, or what I foolishly thought was final, she exerted her informed opinion over both meta issues (cutting three entire chapters from The Inheritance, markedly expanding the epilogue in Breaking the Line) and the most granular tweaks (how best to describe the way a battered briefcase looked).

The epitome of Alice’s righteous obsessiveness for me was the indignant phone call I received from her about the captions I had submitted for the photo insert in Breaking the Line. Didn’t I know every caption had to tell a story? And didn’t I know all the captions together had to add up to a larger story? I was in a cab on the way to Kennedy airport for a European vacation when I took that call, but you can be sure I rewrote those captions before takeoff.

I wish I had a happier ending to conclude these memories of Alice. It was my decision, not Alice’s, to part ways on my current book, about Hubert Humphrey and civil rights. In one respect, I have been proven right. For the only time in our relationship, our vision of a book had diverged so greatly that the difference could not be bridged. And, as it turned out, had I signed with Alice, my book and I would now be orphaned. But when my agent and I submitted that proposal to all the other major publishers, we learned the very hard way that loyalty of the Mayhew kind is a rare and vanishing resource.

Great works of nonfiction will continue to be written and published, but there will be no replacing the influence and integrity of Alice.