Rebecca Rukeyser on Sleaze, Male Rot, and Writing a Horny Novel

Tony Tulathimutte Talks to the Author of The Seaplane on Final Approach

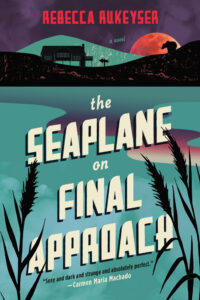

Rebecca Rukeyser has lived all over the fucking place—Istanbul, Busan, Berlin, Iowa City, Davis, Brooklyn. A season in Shanghai working for an ad agency that officially disavowed the existence of free will. And Kodiak, Alaska, where as a teenager she worked at a cannery; this inspired the setting of her moody, broody debut novel The Seaplane on Final Approach, about a woman named Mira looking back on a summer in her youth working at an Alaskan wilderness lodge.

I’ve been a fan of Rebecca’s work since we met in grad school, where she briefly thought I was her enemy, and if I had to put a theme to her work, it would be “sexy nausea,” the hot-faced convulsive kind. Like her two dads, Davids Cronenberg and Lynch, she’s always had a knack for details so disgusting they become attractions (I remember one story where a woman sailing to America watches leeches “flipping in a bowl of water”) but her real talent is much subtler: her ability to coax out the sinister and squeamish side of the seemingly ordinary through close inspection, like the phrase “apple-cheeked,” or Bill Hader’s face. (Those aren’t in the book, just ones she told me before.)

The Lavender Island Wilderness Lodge makes an ideal setting for these talents—a place that exists to introduce tourists to the majesty of Alaska’s wilderness, run by people whose idea of fun is hunting octopuses “by luring them out of their holes with syringes full of bleach.” Mira, our intrepid 18-year-old protagonist, observes the goings-on through a geostorm of hormones, finding sexy nausea in puffins, a piece of foil, the phone book, pie making, and four-door sedans.

As an 18-year-old myself, I was excited to ask Rebecca all sorts of questions about her book in the sultry and glovelike embrace of a Lit Hub article. This interview was for some reason conducted over email, even though at the time she was literally staying at my apartment.

*

Tony Tulathimutte: This is a book obsessed with “sleaze,” but the way Mira thinks of it seems to be different than the standard conception, which to me is like: old Times Square, cheap fake-wood-panel motels, Pete Doherty, excessive pomade and chest hair. It’s always been an urban phenomenon to me, now that I think about it. What was the idea behind choosing the setting of rural Alaska to play this theme out?

Rebecca Rukeyser: Sleaze is in the eye of the beholder! And I completely agree on the motels—easy-to-wipe-down laminate pine is definitively sleazy.

So the origins of sleaze in this novel was really an exercise in perversity. Seven years ago I had mono and just binged on Westerns. I was too sleepy to read anything quieter or less violent. So I went through, like, Shane and Butcher’s Crossing until I was too tired to read and then just lay around, thinking a ton about the genre.

And one defining feature of Westerns is that the protagonist is often this young guy obsessed with chasing after his idealistic-to-the-point-of-being-addled theories having to do with white American mythology. These theories are always about purity, either the purity of the land or the purity of the Pioneering Spirit or of Lonesome Soul Searching or what have you. I was getting kind of peevish through my mono and thought, well, someone should write something where the protagonist chases addled theories about something that’s the complete opposite of lofty purity. Sleaze.

So the origins of sleaze in this novel was really an exercise in perversity.And, as these things do, this dovetailed with biography. I spent a chunk of time working seasonally in Alaska—commercial salmon fishing, in a cannery, in a truckstop, in hospitality—and realized that the way Alaska sells itself as a tourist destination is really steeped in the ideas of the Western. Not only is the state motto The Last Frontier, but it plays up the angle of purity: pristine nature, idealized, uncompromising Alaskan spirit, where you can go to find the real (pure) you.

But at the same time, it’s a place that infamously attracts total weirdos with checkered pasts and asks no questions. There’s a reason the Breaking Bad sequel movie had Jesse Pinkman move to Homer. There’s a tremendous and tremendously fascinating gulf between the ad campaign of pure Alaskan nature experience and the ex-con who runs the kayak rental.

TT: Of course it’s hard to talk about purity without mentioning gender—I feel like Alaska and sleaze are both gendered concepts as well, in that Alaska is the state with the highest percentage of men and projects that image of calloused, sunburnt masculinity. (One character quotes the Alaskan proverb: “The odds are good, but the goods are odd.”) But the narrator Mira is an 18-year-old “nice girl from a nice home,” who spends the book fantasizing about her tattooed fisherman step-cousin who’s missing a front tooth. Do you think of this as an anti-Western? A Northwestern? Is the idea here to subvert the romance that comes with the genre, or just pervert it?

RR: Oh, for sure I’m more interested in perversion than subversion!

I don’t think of it as an anti-Western, because there are so many novels that better fit that particular bill, and actually subvert or upend the conventions of the genre and play more fully with breaking Western rules. I very much had Westerns on the brain when I started writing, but my intention was not to upend the conventions of the genre as much as work on distorting them, warping Western elements until they looked a little… off.

Like: homesteads feature heavily in Westerns as these ultimate safe, cozy spaces, where you can ride in out of the rain and get hot stew and blankets. I wanted to keep all of this—stew, blankets—but keep the action there in the homestead until the nicety of the situation became oppressive. Kind of like stretching out the telling of a joke until it stops being light and full of potential hilarity and becomes uncomfortable and full of potential—well, the hilarity stays but is joined by menace.

The Ed character was partially formed from the same impulse. Both Westerns and straight-up romance novels always have “rugged hot guy” with that calloused, sunburnt masculinity you mentioned. But you toggle rugged hot guy a little further into “rugged” and interesting questions arise: how rough can he get before he starts getting a little sinister? When does attraction start to contain a little revulsion?

I very much had Westerns on the brain when I started writing, but my intention was not to upend the conventions of the genre as much as work on distorting them, warping Western elements until they looked a little… off.Even his name is a hat-tip to that. Edward is a name steeped in rugged hot guy tradition, of hot that gets weird when you look at it too long. Edward Rochester in Jane Eyre is a hot busted drunk, Edward Cullen is a hot homicidal corpse, etc. But they’re granted salvation because of their immoderate, prolonged yearning. Enter Ed; enter Mira’s immoderate, prolonged yearning.

TT: So that actually puts your book in yet another genre, the capital-R Romantic novel. And it reminds me of the time we watched Barry and talked about how Bill Hader is on a spectrum of “hot decaying men” along with, I think, Willem DeFoe? You broke down this sort of taxonomy of “male rot,” what were those categories again?

RR: Ah damn, I should have written that down. I think we were talking about male actors that lean into their decay—that sort of make their actorly persona “I’m unravelling and/or rotting and here’s the physique to go along with it.” And my thought is there are two ways to telegraph rottenness: looking incredibly haggard and unkempt and just hung out to dry and, paradoxically, trying to look put together and, in failing, looking even more rotten.

The patron saint of the first school—full throttle haggard—is Steve Buscemi. He was just this absolute angel-faced baby and then one day someone decided: nope, it’s time for you to look like you sleep in your car and have nightmares every night. This ends up being surprisingly compelling in many instances.

An example of the second—trying to look fresh-faced and paradoxically looking even more rotten—is Stellan Skarsgård. There’s a real thwarted middle-manager vibe here, rage-eating a sub sandwich in his car. This is just straight-up terrifying.

TT: This sort of aesthetic connoisseurship is pretty characteristic of the book, actually—I feel like a lot of it involves Mira just staring and staring and staring at stuff in pure horniness, like even just Ed’s name in the phonebook, until out pops a transcendental hallucination or bizarre insight or recovered memory. And yet for all this buildup, nothing’s ever really consummated; the sex that occurs in the books happens offstage. I wondered at the narrative purpose of this lack of release, whether it had something to do with her reasons for being in Alaska. That declaration she makes toward the beginning, “My ferocity was leveled at becoming”—does she want to become more than she wants to come?

RR: Oh, huh. Not more; Mira doesn’t want anything more than she wants to come. She spends most of the novel working towards orgasm, either actively jerking off or, like you said, sort of insisting on projecting the erotic into things that aren’t necessarily hot (phone books) and spending time in a lustful fugue state.

But that’s not independent from her process of becoming, because what she doesn’t really have like Goal A) My Future and Goal B) My Sexual Fantasies. Instead she has a twofer. She has a watertight plan for how her life is going to be and it’s: okay, I’m going to go to Alaska and become Alaskan and live with Ed and it’s just going to be a nonstop sleaze-and-sex buffet, forever.

She approaches her future and her sexual fantasies in a way that is, for lack of a better word, pigheaded. It’s an act of will as well as horniness. She can have the life she wants if she wants it, goddamn it. She can look at whatever—a wall, a phone book, a scrap of foil—and turn something weighted with erotic potential. She’s under the impression that she can breathe and bend her entire life into whatever lewd balloon animal form she wants it to have.

There are few character traits that I enjoy more than dogged, but irrational horniness is right up there.

Unmet want only moves you so far forward and then has a tendency to keep you trapped.TT: Dramatizing a really specific mode of sexuality seems to be part of the book’s project, and I’m finding it hard to articulate what it is. It’s not an explicit book.

RR: Someone pointed out on Twitter recently that “horny” and “fucky” are different qualities; literature that is “horny” isn’t necessarily “fucky” and vice versa. Of course a book can be both horny and fucky, or neither.

I think my novel fits pretty neatly into the horny-but-not-fucky category. And that was intentional for a couple of reasons.

For one: when there’s the pressure exerted by un-fucky, unfucked horniness, the narrative warps in interesting ways, things get curtailed, things double back on themselves. Unmet want only moves you so far forward and then has a tendency to keep you trapped.

For two—and I think this gets back to what you were mentioning about it not being an explicit book—I wanted to stay in Mira’s head, at the base of this sheer unbroken wall of desire. She’s laser-focused on the narrative of her masturbatory fantasies, including those looping, inane preambles to sex—like the part in the porn where the plumber is actually trying to fix the faucet, or whatever. I wanted to stay there, zeroed in on what’s happening inside Mira’s head instead of zooming out slightly and detailing in an explicit way what she’s doing to her body, or having her register every sensation.

Part of that, I guess, was having her horniness be untethered to self-actualization, self-acceptance. There are so many men in novels that jerk off without finding themselves; far too often, women characters are going on these Hitachi-powered journeys of empowerment. It’s the same kind of infantilizing as articles that say “you should masturbate because it helps raise self esteem and lower cortisol,” or referring to female masturbation as, like, “rub a nub nub.”

There are so many men in novels that jerk off without finding themselves.TT: Jesus Christ, rub a nub nub? I know there aren’t many euphemisms for female masturbation and the ones I can think of are all quaint and horrible and never used in earnest. Dialing zero, flicking the bean, jilling off. Why is that?

RR: Because women masturbating—women desiring more broadly—still gets shuffled into the category of “the best” or “the worst.” A “radical act of literal self love” or “being a ruined woman.” There’s still not a whole lot of nuance, “because she was feeling thwarted and listless and also had just watched Secretary.”

I think all the good euphemisms men get exist because men masturbating is allowed to be everything: the best, the worst, sad, lonely, hopeful, romantic, sinister, lazy, passionate, silly, quaint, horrible, clownish. With that range, the euphemisms you get don’t all have to be cutesy. You can say “whacking it” and it sounds kind of menacing or you can say “pulling the pud” and it’s hilarious and brings to mind, like, pug dogs and English puddings.

I dunno, maybe this needs to be reverse engineered. Maybe more euphemistic variety is the first step. “She spent the evening furiously curing hysteria.”

TT: She spent the evening paddling the canoe. Taking fingerprints. Catching a Digglett.

RR: Yes. Damn. You missed your calling as an evil branding genius for—well, I’m not sure what brand this is. Scratching the turntable?

TT: Doubting the Thomas.

RR: I can’t visualize that one?

TT: Manually stimulating the clitoris to orgasm.

RR: Tony.

TT: Throwing the Heart of The Ocean into the North Atlantic.

RR: Gloria Stuart’s little “Eep!” noise.

TT: Last question, mostly for my own sake. What is the sleaziest place in the continental US, including all its territories, protectorates, and federal districts?

RR: The circular driveway outside the Plaza Hotel and Casino at the end of Fremont Street in Las Vegas.

_________________________________

The Seaplane on Final Approach by Rebecca Rukeyser is available from Doubleday