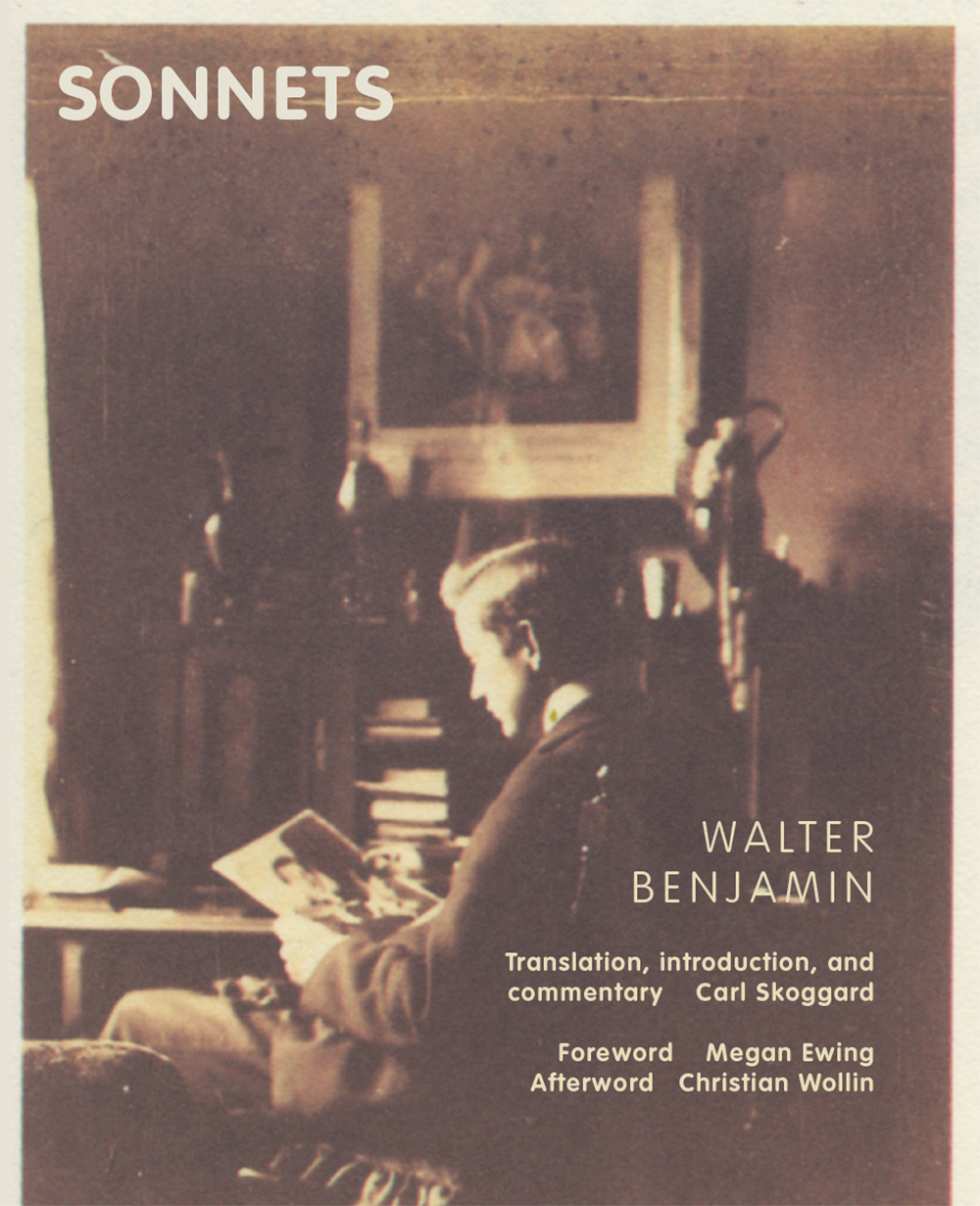

Read Early Sonnets By Walter Benjamin, for the First Time in English

Heartbroken, One of the Great Thinkers of the 20th Century Turned to Poetry

That Walter Benjamin wrote an extensive series of sonnets to mourn the death of Christoph Friedrich Heinle, a promising poet who took his own life at the age of 20, days after the First World War had begun, is not widely known. Benjamin worked on these sonnets for a long time, possibly a decade. Now and then he would read from them to his household circle; in 1923 he thought to send samples to Florens Christian Rang, a distinguished older man with whom he had come to be on excellent terms and who might have passed them on to a prospective publisher. But the poems appear to have stayed with Benjamin. They were among the writings he eventually entrusted to Georges Bataille in 1940 for safekeeping, when continuing in France was impossible. Publication would wait until 46 years after Benjamin’s death; the present translation makes them available to readers of English for the first time.

![]() Read sonnets 1, 34, and 45 below.

Read sonnets 1, 34, and 45 below.

![]()

Benjamin the writer of sonnets seems to raise a special problem for his admirers. Even today, the fact that they are the central undertaking of his early adult years has not registered in the literature. Perhaps this is because people cannot bring themselves to consider Benjamin as a poet, or cannot conceive of his having turned to the writing of poetry to confront crucial issues in his life. Defining Benjamin has never been easy. Indeed, during the years he was producing his sonnets, young Benjamin was also imagining that he would be the next to advance German metaphysics. As well, he saw himself becoming the leading critic of German literature. In the end, however, despite highly original contributions to both fields, Benjamin would not bequeath anything like a life’s work to either.

As Hannah Arendt pointed out in her seminal essay, whatever Benjamin left for posterity was altogether sui generis. Nothing he did resembled what had been written by others before him or was likely to be repeated, least of all by himself. Moreover, Benjamin was in everything he touched an amateur:

His erudition was great, but he was no scholar; his subject matter comprised texts and their interpretation, but he was no philologist; he was greatly attracted not by religion but by theology and the theological type of interpretation for which the text itself is sacred, but he was no theologian and not particularly interested in the Bible; he was a born writer, but his greatest ambition was to produce a work consisting entirely of quotations.

This list concludes with the observation that Benjamin “thought poetically, but he was neither a poet nor a philosopher.”

Certainly Benjamin’s sonnets are unlike any others. Arendt, a friend to Benjamin during his last Paris years, may not have known of them. Few people were ever informed of the project; fewer still were shown poems. During the years he was actively at work on the sonnets, only Gershom Scholem, who was his closest associate and heard Benjamin read some of them, was fully initiated and could sense their great importance for him. To a large extent, therefore, their limited reception must be laid at the door of Benjamin himself, always inclined to secrecy about what he cared for most. Subsequent to Benjamin’s death, those who had known him best simply assumed that certain sonnets dedicated to a deceased friend of his early youth were among his lost works. The sonnets would be rediscovered in Paris, in the Bibliothèque nationale, in 1981. But so far their unearthing has not granted them a firm place in anyone’s understanding of Benjamin and his work.

In turning to sonnets, Benjamin took care to heed traditional formal patterns. In his hands, however, respect for convention only contributes to an essential strangeness. The strangeness begins with the simple fact that he would spend years producing so many of them—73 in total—for a dead (male) friend. But in the desolation of the First World War, writing sonnets became for him a secret obsession. These were otherworldly sonnets in which Benjamin looks to a far-off constellation of unchanging metaphysical reality for consolation. They have nothing to do with the vicissitudes of a love relationship in the here and now, as Shakespeare’s do—though like his predecessor, Benjamin is a poet-lover seeking special favor. That favor will be rarified spiritual communion with the friend, achieved through the very process of mourning him. At the same time, Benjamin’s sonnets are his idiosyncratic response to the conflict around him, about which he was largely silent otherwise.

Apart from what one gleans from the poems, evidence of the relationship between Benjamin and “Fritz” Heinle comes chiefly from letters Benjamin penned during the spring and summer of 1913, and from the Berlin Chronicle, a memoir of his early years in Berlin written shortly before Benjamin left Germany for good—that is, nearly two decades after the events being recalled. The letters, filled with youthful élan, let us trace the beginnings of a powerful attraction of opposites between the twenty-year-old Benjamin and an unconstrained and impetuous Rhinelander not quite two years his junior. Their meeting took place in the picturesque subalpine town of Freiburg im Breisgau, where both had enrolled in the university. Within weeks they were hiking together in the surrounding mountains and drinking together in taverns. Benjamin’s missives, addressed to former schoolmates in Berlin, show that almost immediately he sought to have Heinle’s poetry published—efforts proving fruitless then and later. The most interesting of Benjamin’s comments indicate that he, Benjamin, so highly reserved and intensely intellectual, was falling under the sway of his new friend.

Heinle is first mentioned in a positively chatty communication dated 29 April 1913 which Benjamin addressed to Herbert Blumenthal (later Belmore):

And look at the sort of people I associate with! You will be hearing about this also from Sachs. There is Keller, who has the beginning of a new novel that is significant; he has a pretty girlfriend whom I often see. There is Heinle, a good young fellow. “Tipples and eats hearty and makes poems.” They are supposed to be very nice. I’ll soon be hearing a few. Forever dreaming and German. Not well-dressed.

Franz Sachs was another Berlin school friend. The letter continues: “Take note, I go around only with Christians here, and please tell me what that means.” Nearly all the letters surviving from this period of Benjamin’s life were addressed to Jewish peers from his own assimilated Berlin background.

The Freiburg letters routinely refer to Heinle. One to Sachs (4 June 1913) shows Benjamin already intent on having “odes” by Heinle published. Another to Blumenthal dated June 7 contains Heinle’s “latest”: Portrait. With six musical lines of rhyming iambic pentameter, the poem seizes on a moment of erotic surrender:

From yellow linen rises tan and clear

The slender neck upright.

Yet full aware

Of feasts bestowed down sinks the singéd pair

In handsome arcs to cambered pleasure.

Like dark grapes spring the pair of lips

With sudden ripeness to the heaving breast.

By July 3, Benjamin can speak of Heinle and himself to Blumenthal as a pair of friends detached from the rest:

Heinle has turned out to be the only student with whom I continue to be on truly personal terms. Keller is now neurasthenic… Lately I was witness to a frightfully embarrassing scene… The fact that Heinle and I had nothing whatsoever to do with it—but were seen by both parties as uninvolved, should provide you with the evidence of our defined and thoroughly isolated position.

The same letter lays bare the closeness which was developing between these two and how Benjamin nevertheless suffered from loneliness:

Recently I made the acquaintance of a female student from Essen, whose name is Benjamin. We took a walk on the Schönberg… one of the fairest peaks I know. I want to go there at night some time with Heinle. We talk of many things easily and gaily—each time when I think of this walk, it comes to me how greatly I lack for people here. Heinle is really the only one.

Some of the last mentions of Heinle from Freiburg are in his defense, against criticism that had been directed against both his prose and his poetry. Now Benjamin concedes that Heinle expresses himself from the heart rather than through ideas (letter to Sachs, July 11) and that a certain poem of his is “hard to understand and not perfect” (to Blumenthal, July 17). Most revealing is the confession to Blumenthal which follows: “Here [in Freiburg] we are perhaps more aggressive, more vehement, and less inclined to reflect (literally!). What I really mean is: he is so and I feel it after him, with him, and am often so myself.”

That autumn the young men migrated to Berlin to attend university there. But now enthusiasm for Heinle’s poetry is no longer a feature of Benjamin’s correspondence. Instead his references, for the most part in passing, have to do with their frenzied activities within the “youth culture movement,” or Jugendkulturbewegung. Already in Freiburg both had been active in this movement, through which university students were beginning to ask for more say in their education and development, and to advocate on behalf of others still younger than themselves.

The more radical students envisioned a fully autonomous youth culture which would usher in the regeneration of Wilhelmine society as a whole. And though it was always a tame affair (violence was never threatened), the Jugendkulturbewegung alarmed conservatives. Every month its journalistic organ, Der Anfang, issued a summons to youth: to create itself, to harness that yearning for an ideal which belonged to it alone—and to resist being molded for the existing order through the patriarchal family, schools and universities, and the church.

Along with his friend Heinle, Benjamin soon assumed a prominent role in the student leadership in Berlin. The Jugendkulturbewegung, however, was prey to infighting; and eventually Benjamin and Heinle, too, found themselves at odds. One of Benjamin’s letters of the time contains his gravely beautiful account of the quarrel which briefly interrupted their friendship:

Yesterday evening Heinle and I found ourselves together on the way to Bellevue station. We spoke only of meaningless things. Then all at once he said: “Actually, I should really have a great deal to say to you.” Whereupon I invited him to go right ahead, that it was high time. And since he really did want to tell me something, I was eager to hear it and at his urging went with him to his room.

At first we went over and over what had happened, trying to explain, and so forth. But soon we felt what it was about, and said as much: That it was very hard for the two of us to separate from each other. And I realized one thing that was the important aspect of this discussion, namely, that he knew perfectly well what he had done, or rather, it was no longer for him a matter of “knowing,” so definite and necessary did he really view our opposition to each other, just as I had expected he would. He placed himself over and against me in the name of Love, and I countered with the Symbol. You understand the simplicity and the richness of the friendship for us, how for us it contains both these things. The moment came when we confessed that we were up against fate: we said to each other that each could be in the other’s place.

With this discussion, which I am scarcely able to relay to you in this letter, we each withstood the sweetest temptation. He withstood the temptation of enmity, and offered me friendship, or at least brotherliness, from then on. I withstood by rejecting—you do see—what I could not accept.

Sometimes I have thought that we two, Heinle and I, understand each other the best among all the people we know. But this is not quite right. Rather: Even though we are each other, each must of necessity stay true to his own spirit [Geist].

The remainder of the letter confirms that tensions between the friends had grown out of differences within the youth culture movement. Yet the specifics of their quarrel are hard to discern. How it was resolved sounds cryptic, too, in Benjamin’s telling, found in his Berlin Chronicle (notice 12): “Even now I am able to recall the smile which made up for all the dreadfulness of the weeks of our separation, and with which he [Heinle] made what seemed an almost irrelevant mention of a magic formula, healing the injured party [Benjamin].”

Then, abruptly, war came and the “youth culture movement” was deprived of relevance. Most young men who were Benjamin’s age rushed to arms. But during the night of August 8, 1914, Fritz Heinle, deciding otherwise, ended his life. With him was his lover, Rika Seligson. The Berlin Chronicle relates that on the following morning Benjamin awoke to an express letter from his friend containing the words: “You will find us lying in the Heim.” The “Heim” was a meeting place for students belonging to the group led by Benjamin; here the two had used kitchen gas to asphyxiate themselves. Various local papers of the day were satisfied that the couple had been unhappy in love. Persons closest to them knew more.

The Berlin Chronicle also speaks of the confusion and excitement of the first days of the conflict. Benjamin and other members of his circle had “huddled together” in the Café des Westens on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm to choose which garrison they might apply to as a group. “My place, too, was among the surge of bodies then swelling in front of the garrison gates,” Benjamin would recall,

no matter how reserved my thinking, according to which one’s sole course could be to secure a place among friends in the unavoidable call-up. Admittedly this was only for two days: On the eighth the event intervened which caused this city and this war to sink from my sight for a long time.

In the aftermath of the suicides, rather than volunteer to become a soldier, Benjamin obtained the first of several military deferments. And he did not hesitate before resigning his post as student leader. In the summer of 1915 he left Berlin for Munich, where he no longer involved himself in politics of any sort and did not care to discuss the war, whether in correspondence or in conversation. Nor would he discuss the disappearance of his friend. In 1917 he decamped for Switzerland; not until 1920 did he return to live in Germany.

Sonnet 1

Disburden me of Time from which thou’rt vanished

And of thy presence free me from within

As in the twilight hours red roses free themselves

From all mere marriedness of things

The heartfelt homage and the bitter voice

I forego calmly and thy burning lips

And yet more burning brow enshaded purple

Just below the black gleam of thy hair

So may that image fail me too of praise

And ire which thou wouldst offer

Underway while very like a prince

Thou didst the banner bear its symbol to unriddle

Plant in me thy sacred Name instead

Name without image Amen without end.

Sonnet 34

I sat one night to ponder on myself

And round me thy sweet life did stir

The mirror of my mind glanced back

As hadst thou just looked out from in its depths

Then came the thought: Thou sucklest me

Into thy breath I shall my self surrender

For like grapes hanging are thy lips

Which have mute witness borne to inmost things

O friend thy presence has been wrested from me

Like one asleep whose hand looks for the wreath

In his own hair so in dark hours I for thee

Though once thy cloak did round me go

As were there dancing and from within the midnight throng

Thy look did snatch the breath out of my mouth.

Sonnet 45

My Soul why art thou always in search of the Beautiful one?

Long is he dead and the rotating globe so

Attends to its spinning that no one still misses the hero

My Soul why art thou always in search of the Beautiful one?

Why dost wake me O Lord with such weeping and groaning?

Ah I was looking to sleep and lamenting disfigures

My desolate state in which Desolate one thou dost share

Why dost wake me O Lord with such weeping and groaning?

And so one night I held in my heart a debate

Falling mute and ashamed I determined on silence

No longer my sorrow to show to my Soul

No more to wake her my griefs to assuage

Though see from her mouth sleeping she allowed to ascend

So many a sorrowful song Her tears flaring like candles.

__________________________________

From Sonnets, by Walter Benjamin, courtesy FENCE Books.

Carl Skoggard

Carl Skoggard is a writer and a translator.