Read 20 Famous Authors’ Very First Published Short Stories

From Jesmyn Ward to Mary Gaitskill to William Faulkner

Sometimes it feels as though our favorite writers burst from the womb fully-formed, slinging wisdom and polished drafts from the crib. But even the most legendary of writers had to start somewhere—and often that somewhere was in the under-read pages of a literary magazine. (Famous authors: they’re just like us!) In the interest of looking back to some very auspicious beginnings, below I have collected 20 famous authors’ first published stories, each of them available to read online, and presented here with their opening lines to pique your interest (or not, as the case may be). NB that I’ve discounted true juvenilia here, though some of these are indeed from their authors’ teen years. Some show only glimmers of future stardom—and some are, well, pretty fully-formed already.

Mary Gaitskill, “Something Better Than This“

Mary Gaitskill, “Something Better Than This“

originally published in Branching Out, 1978

It’s one of those raw, wrung out Yonge Street Saturday mornings. The smog-gray sky is just congealing into blue over the buildings and concrete. A dozen or so kids in denim are lollygagging outside Mr. Submarine sandwich plaza. They’re wearing T-shirts with messages like “Have a shitty day” emblazoned on them, and they all look bewildered. They aren’t the only people in the street. The old men in coats are shuffling along, mumbling in a phlegmy secret language and spitting all over the crusty sidewalk. Then there’s the woman in a short, pubis-gripping skirt and the occasional cop floating by in a yellow cruiser, eating a choco-cherry donut and beating out “Here Comes My Baby” on the dashboard.

Edith Wharton, “Mrs. Manstey’s View“

Edith Wharton, “Mrs. Manstey’s View“

originally published in Scribner’s Magazine, July 1891

The view from Mrs. Manstey’s window was not a striking one, but to her at least it was full of interest and beauty. Mrs. Manstey occupied the back room on the third floor of a New York boardinghouse, in a street where the ash-barrels lingered late on the sidewalk and the gaps in the pavement would have staggered a Quintus Curtius. She was the widow of a clerk in a large wholesale house, and his death had left her alone, for her only daughter had married in California, and could not afford the long journey to New York to see her mother. Mrs. Manstey, perhaps, might have joined her daughter in the West, but they had now been so many years apart that they had ceased to feel any need of each other’s society, and their intercourse had long been limited to the exchange of a few perfunctory letters, written with indifference by the daughter, and with difficulty by Mrs. Manstey, whose right hand was growing stiff with gout. Even had she felt a stronger desire for her daughter’s companionship, Mrs. Manstey’s increasing infirmity, which caused her to dread the three flights of stairs between her room and the street, would have given her pause on the eve of undertaking so long a journey; and without perhaps, formulating these reasons she had long since accepted as a matter of course her solitary life in New York.

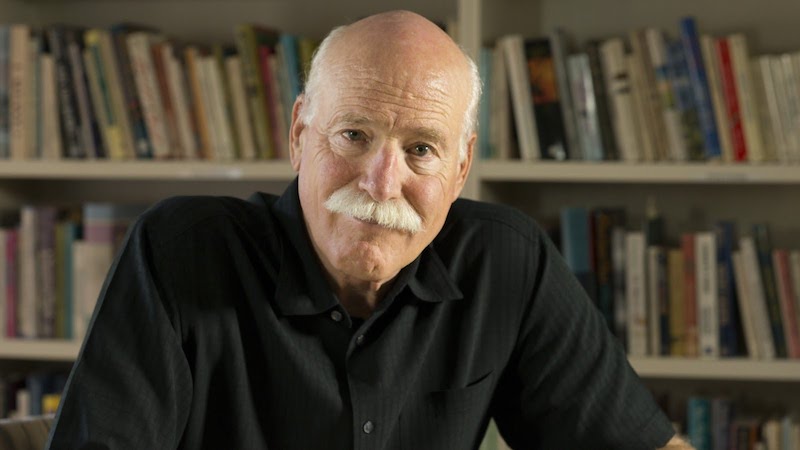

George Saunders, “A Lack of Order in the Floating Object Room“

George Saunders, “A Lack of Order in the Floating Object Room“

originally published in The Northwest Review, Volume 24, Number 2, 1986

It’s like this, and it is no dream: First off, a plastic palomino and its stiff-armed rider float above a toybox. The rider is a dyed Custer, and everything’s red. I mean boots and kerchief and holster and eyebrows even. He is one ruined and reduced cavalryman, he was poured and solidified with horribly bowed legs, simply because his only reason for existence is to straddle the palomino. Denied Comanches. But the horse and rider float and revolve anyway, on the lookout for marauders. They rotate at about a revolution a minute, as per specs. Also: a velour basketball, half the size of a real basketball, hangs mid-aired over a crib. In the closet, the arms of tiny jackets and sweaters wave and salute wildly. The threads of the carpet flatten out like grass under a helicopter, and then circular waves run outward from the middle of the room. When the waves die down, it’s just a regular carpet again. The whole cycle takes three and a half minutes. An empty rocking chair rocks faster than any mortal granny could.

Jesmyn Ward, “Cattle Haul“

Jesmyn Ward, “Cattle Haul“

originally published in A Public Space no. 5, 2008

It’s easier driving through the country, especially when you doing a cattle haul. Two lanes on one side and two lanes on the other. Switch lanes and pass. At night, like now, the signs sharp and clear. The trees like waves at the side of the road, all black and blue, coming in and going back out like a tide. Ain’t no lights to distract me, to crowd up around me. Just taillights, red lights, like ants, leading me in a line westward.

Part of me want to stop. Part of me want to pull over on the side of the road and turn the rig off and start walking back to where I come from; want to get out the rig and leave it all here in the dark. But I press the gas hard and daydream about flying past the flatlands, speeding to dry, parched Texas, and through the desert to Phoenix to drop these cattle off, but they got weigh stations and state troopers, and cars and rigs like bad potholes: they waiting just to slow you down and fuck you up. I see a deer by the side of the road, two of them, night-feeding by the pines. They don’t even flinch when I pass by.

Jack London, “A Thousand Deaths“

Jack London, “A Thousand Deaths“

originally published in The Black Cat, May 1899

I had been in the water about an hour, and cold, exhausted, with a terrible cramp in my right calf, it seemed as though my hour had come. Fruitlessly struggling against the strong ebb tide, I had beheld the maddening procession of the water-front lights slip by, but now a gave up attempting to breast the stream and contended myself with the bitter thoughts of a wasted career, now drawing to a close.

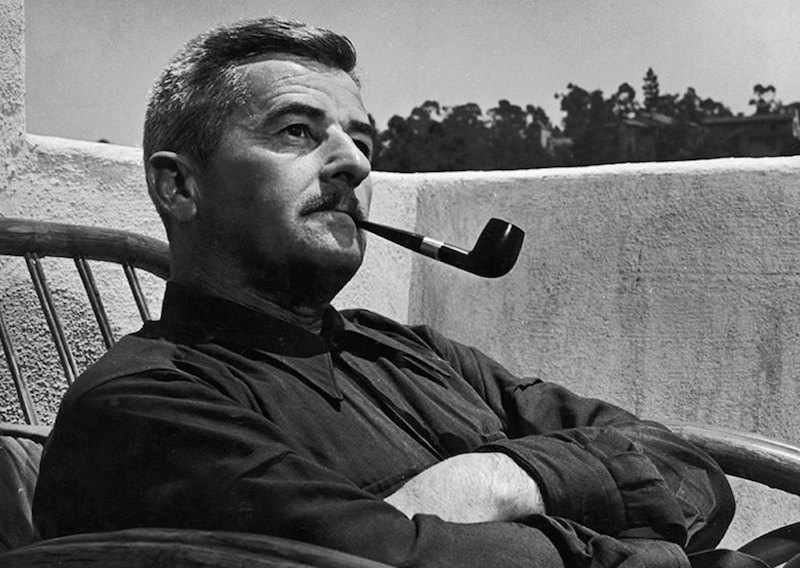

William Faulkner, “Landing in Luck“

William Faulkner, “Landing in Luck“

originally published in The Mississippian, November 26, 1919

The machine levelled off and settled on the aerodrome. It turned and taxied back and stopped, headed into the wind again, its engine running idle. The instructor in the forward cockpit faced about and raised his goggles.

“Fairish,” he said, “not so bad. How many hours have you had?”

Cadet Thompson, a “barracks ace,” who had just made a fairly creditable landing, assumed an expression of assured confidence.

“Seven hours and nine minutes, sir.”

“Think you can—hold that stick back, will you?—think you can take her round alone?”

“Yes, sir,” he answered as he had answered at least four times a day for the last three days, with the small remaining part of his unconquered optimism in his voice. The instructor climbed slowly out onto the lower wing, then to the ground, stretching his legs. He got a cigarette from his clothes after a fashion resembling sleight-of-hand.

John Cheever, “Expelled“

John Cheever, “Expelled“

originally published in The New Republic, October 1, 1930

It didn’t come all at once. It took a very long time. First I had a skirmish with the English department and then all the other departments. Pretty soon something had to be done. The first signs were cordialities on the part of the headmaster. He was never nice to anybody unless he was a football star, or hadn’t paid his tuition or was going to be expelled. That’s how I knew. He called me down to his office with the carved chairs arranged in a semicircle and the brocade curtains resting against the vacant windows. All about him were pictures of people who had got scholarships at Harvard. He asked me to sit down.

Kelly Link, “Water Off a Black Dog’s Back“

Kelly Link, “Water Off a Black Dog’s Back“

originally published in Century, 1995

Rachel Rook took Carroll home to meet her parents two months after she first slept with him. For a generous girl, a girl who took off her clothes with abandon, she was remarkably close-mouthed about some things. In two months Carroll had learned that her parents lived on a farm several miles outside of town; that they sold strawberries in summer, and Christmas trees in the winter. He knew that they never left the farm; instead, the world came to them in the shape of weekend picnickers and drive-by tourists.

“Do you think your parents will like me?” he said. He had spent the afternoon preparing for this visit as carefully as if he were preparing for an exam. He had gotten his hair cut, trimmed his nails, washed his neck and behind his ears. The outfit he had chosen, khaki pants and a blue button-down shirt — no tie — lay neatly folded on the bed. He stood before Rachel in his plain white underwear and white socks, gazing at her as if she were a mirror.

Anthony Marra, “Chechnya“

Anthony Marra, “Chechnya“

originally published in Narrative magazine, 2009

After her sister, Natasha, died, Sonja began sleeping in the hospital. She returned home to wash her clothes a few days a month, but those days became fewer and fewer. No reason to return, no need to wash her clothes. She only wears hospital scrubs anyway.

She wakes on a cot in the trauma unit. She sleeps there intentionally, in anticipation of the next critical patient. Some days, roused by the shuffle of footsteps, the cries of family members, she stands and a body takes her place on the cot and she works on resuscitation, knowing she is awake because she could dream nothing like this.

Carson McCullers, “Wunderkind“

Carson McCullers, “Wunderkind“

originally published in Story magazine, 1936

She came into the living room, her music satchel plopping against her winter-stockinged legs and her other arm weighted down with school books, and stood for a moment listening to the sounds from the studio, A soft procession of piano chords and the tuning of a violin. Then Mister Bilderbach called out to her in his chunky, guttural tones:

“That you, Bienchen?”

As she jerked off her mittens she saw that her fingers were twitching to the motions of the fugue she had practiced that morning. “Yes,” she answered. “It’s me.”

Alice Munro, “The Dimensions of a Shadow“

Alice Munro, “The Dimensions of a Shadow“

originally published in Folio, v.4.2, 1950

Miss Abelhart came out of the church alone. Her feet made quick, sharp, certain sounds on the cement steps—not the light tapping sounds pumps make, but harder, heavier claps. Miss Abelhart was wearing oxfords. She wore also a light tweed coat, a straight ugly coat, and an absurd little black hat. Most of her clothes were chosen for their ugliness or absurdity, and she wore them with a certain defiance, as though she proudly recognized in them a drabness closely akin to her own.

Zora Neale Hurston, “John Redding Goes to Sea“

Zora Neale Hurston, “John Redding Goes to Sea“

originally published in Stylus, May 1921

The villagers said that John Redding was a queer child. His mother thought he was too. She would shake her head sadly, and observe to John’s father: “Alf, it’s too bad our boy’s got a spell on ’im.”

The father always met this lament with indifference, if not impatience.

“Aw, woman, stop dat talk ’bout conjure. Tain’t so nohow. Ah doan want Jawn tuh git dat foolishness in him.”

“Cose you allus tries tuh know mo’ than me, but Ah ain’t so ign’rant. Ah knows a heap mahself. Many and many’s the people been drove outa their senses by conjuration, or rid tuh deat’ by witches.”

Truman Capote, “Miriam“

Truman Capote, “Miriam“

originally published in Mademoiselle, 1945

For several years, Mrs. H. T. Miller lived alone in a pleasant apartment (two rooms with kitchenette) in a remodeled brownstone near the East River. She was a widow: Mr. H. T. Miller had left a reasonable amount of insurance. Her interests were narrow, she had no friends to speak of, and she rarely journeyed farther than the corner grocery. The other people in the house never seemed to notice her: her clothes were matter-of-fact, her hair iron-gray, clipped and casually waved; she did not use cosmetics, her features were plain and inconspicuous, and on her last birthday she was sixty-one. Her activities were seldom spontaneous: she kept the two rooms immaculate, smoked an occasional cigarette, prepared her own meals and tended a canary.

Eudora Welty, “Death of a Traveling Salesman“

Eudora Welty, “Death of a Traveling Salesman“

originally published in Manuscript, 1936

R. J. Bowman, who for fourteen years had traveled for a shoe company through Mississippi, drove his Ford along a rutted dirt path. It was a long day! The time did not seem to clear the noon hurdle and settle into soft afternoon. The sun, keeping its strength here even in winter, stayed at the top of the sky, and every tie Bowman stuck his head out of the dusty car to stare up the road, it seemed to reach a long arm down and push against the top of his head, right through his hat—like the practical joke of an old drummer, long on the road. It made him feel all the more angry and helpless. He was feverish, and he was not quite sure of the way.

Flannery O’Connor, “The Geranium“

Flannery O’Connor, “The Geranium“

originally published in Accent, 1946

Old Dudley folded into the chair he was gradually molding to his own shape and looked out the window fifteen feet away into another window framed by blackened red brick. He was waiting for the geranium. They put it out every morning about ten and they took it in at five-thirty. Mrs. Carson back home had a geranium in her window. There were plenty of geraniums at home, better-looking geraniums. Ours are sho nuff geraniums, Old Dudley thought, not any er this pale pink business with green, paper bows. The geranium they would put in the window reminded him of the Grisby boy at home who had polio and had to be wheeled out every morning and left in the sun to blink. Lutisha could have taken that geranium and stuck it in the ground and had something worth looking at in a few weeks. Those people across the alley had no business with one. They set it out and let the hot sun bake it all day and they put it so near the ledge the wind could almost knock it over. They had no business with it, no business with it. It shouldn’t have been there. Old Dudley felt his throat knotting up. Lutish could root anything. Rabie too. His throat was drawn taut. He laid his head back and tried to clear his mind. There wasn’t much he could think of to think about that didn’t do his throat that way.

Imbolo Mbue, “Emke“

Imbolo Mbue, “Emke“

originally published in The Threepenny Review, Winter 2015.

It is a disease of the blood, the doctors told him.

He didn’t ask many questions—he knew about the disease more than some who came in to treat him. He knew that blood is the river of the body and with his being contaminated, his body might soon shrivel up and die like plants on a dried river bank. He knew this truth and yet he showed no great sorrow at the news, only a frail optimism. Bolow and I stayed by his side in those first days, watching as esteemed experts came in pairs and threes and sometimes enough to form a half moon around him. They asked him questions about his appetite, his sleep, his excrements. They read notes in his chart, listened to the beatings of his body, whispered to each other, and left the room with their heads down. The medicine, which the nurses put in through veins in his arm and back, made him drowsy but his sleep was light, ending when he awakened hot and sweaty from nightmares fueled by too many chemicals pumped into his body. After he had toweled off, he would tell us about the nightmares. In one, he was given a glass of blood by a hand without a body, and asked by a baby’s voice to drink it all in one sip. In another, he saw his head on a tray, laughing at him. Over the course of a few weeks, he became lean, then skeletal. His friends filed in and kept his spirits high and he kept theirs high too. When we left his presence we cried, for we saw on that bed a man whose mind and soul were well but whose body appeared to have lost half its contents.

Tobias Wolff, “Smokers“

Tobias Wolff, “Smokers“

originally published in The Atlantic, December 1976

I noticed Eugene before I actually met him. There was no way not to notice him. As our train was leaving New York, Eugene, moving from another coach into the one where I sat, managed to get himself jammed in the door between his two enormous suitcases. I watched as he struggled to free himself, fascinated by the hat he wore, a green Alpine hat with feathers stuck in the brim. I wondered if he hoped to reduce the absurdity of his situation by grinning as he did in every direction. Finally something gave and he shot into the coach like a pickle squirting out of a sandwich. I hoped he would not take the seat next to mine, but he did.

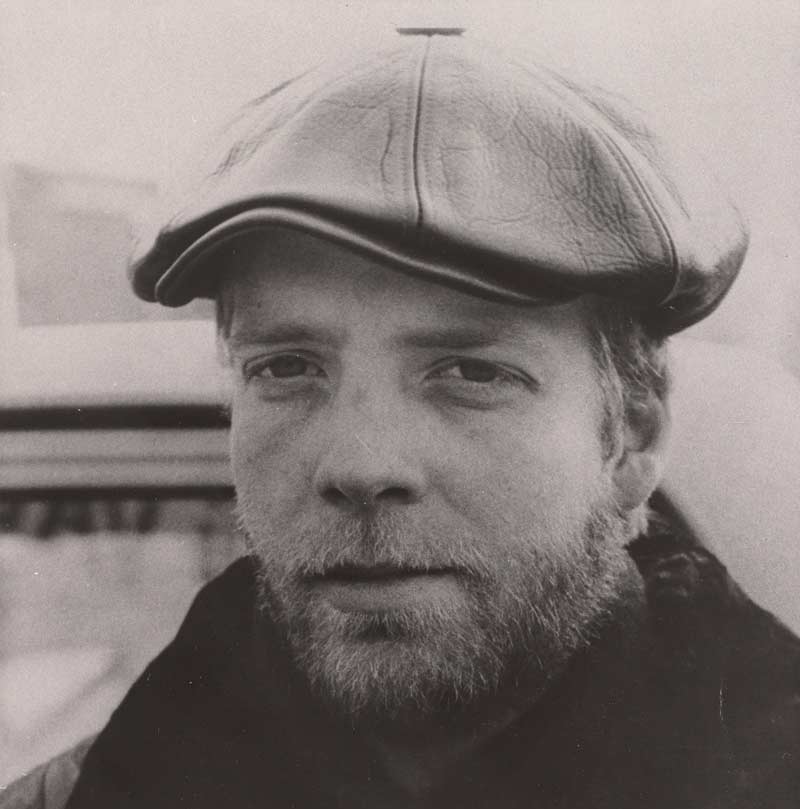

Breece D’J Pancake, “Trilobites“

Breece D’J Pancake, “Trilobites“

originally published in The Atlantic, December 1977

I open the truck’s door, step onto the brick side street. I look at Company Hill again, all sort of worn down and round. A long time ago it was real craggy, and stood like an island in the Teays River. It took over a million years to make that smooth little hill, and I’ve looked all over it for trilobites. I think how it has always been there and always will be, least for as long as it matters. The air is smoky with summertime. A bunch of starlings swim over me. I was born in this country and I have never very much wanted to leave. I remember Pop’s dead eyes looking at me. They were real dry, and that took something out of me. I shut the door, head for the café.

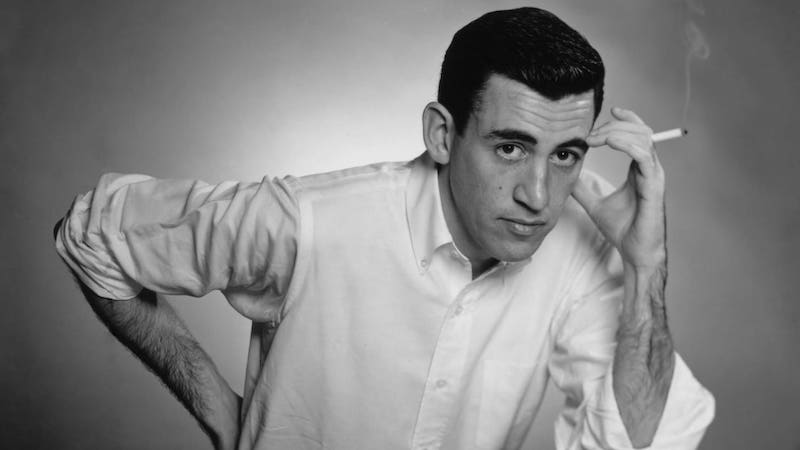

J.D. Salinger, “The Young Folks“

J.D. Salinger, “The Young Folks“

originally published in Story magazine, issue XVI, March-April 1940

About eleven o’clock, Lucille Henderson, observing that her party was soaring at the proper height, and just having been smiled at by Jack Delroy, forced herself to glance over in the direction of Edna Phillips, who since eight o’clock had been sitting in the big red chair, smoking cigarettes and yodeling hellos and wearing a very bright eye which young men were not bothering to catch. Edna’s direction still the same, Lucille Henderson sighed as heavily as her dress would allow, and then, knitting what there was of her brows, gazed about the room at the noisy young people she had invited to drink up her father’s scotch. Then abruptly, she swished to where William Jameson Junior sat, biting his fingernails and staring at the small blonde girl sitting on the floor with three young men from Rutgers.

Mavis Gallant, “Madeline’s Birthday“

Mavis Gallant, “Madeline’s Birthday“

originally published in The New Yorker, September 1, 1951

Mrs. Tracy adored the Connecticut house where she had spent all her summers. Her Husband, Edward, came out weekends. This summer she had two guests. One was Madeline, 17, daughter of an old friend. She was the child of divorced parents and an unhappy girl. Paul, the other guest, was a German boy, a little older, extremely shy and serious. Mr. Tracy felt that the gloomy atmosphere they caused was bad for their daughter, Allie, aged 6. It was Madeline’s birth day but she was in her usual bad temper. Mrs. Tracy tried to smooth things out as best she could so the day would be happy.