Read 13 of the Best Literary Interviews from Interview

RIP a Great American Magazine

This week, employees of Interview magazine, the legendary the arts and culture publication founded in 1969 by Andy Warhol, announced it would be folding and filing for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The magazine had only recently been hit with a lawsuit brought by former editorial director, Fabien Baron, and his wife Ludivine Poiblanc, and at least one employee told the New York Times that they had pretty much seen it coming—but many of the rest of us were shocked. For years, Interview has been a mainstay across art worlds and forms, from literature to visual arts to fashion, and readers—both celebrity and non—have been mourning its demise in recent days. To celebrate the life of the magazine, below I’ve collected a few of my favorite interviews with literary greats that have appeared in its pages in recent years.

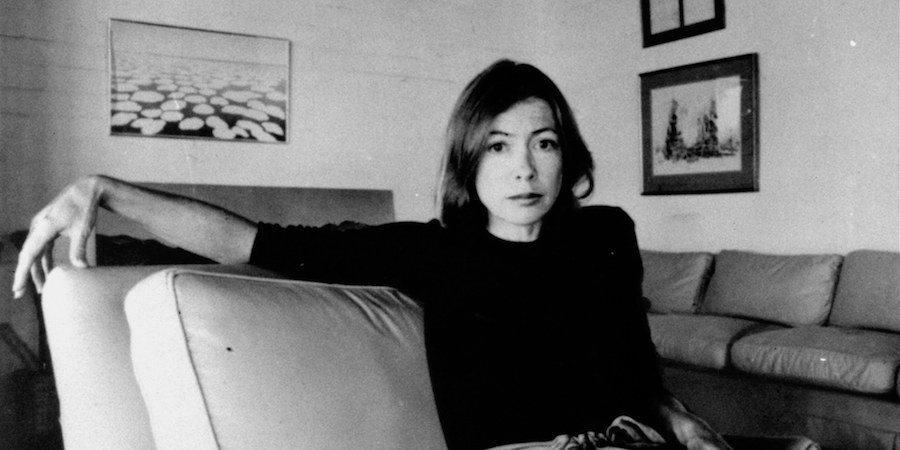

Joan Didion, interviewed by Martin Torgoff, 1983

Joan Didion, interviewed by Martin Torgoff, 1983

On A Book of Common Prayer and the situation in El Salvador:

It’s unrealistic to expect to export our values, our political abstracts. The abstracts that we live by don’t even apply. We’re seriously deluding ourselves by our present course. It has no possibility for a good outcome; it’s against our interests. We’re defeating our best interests there. . . Our best long-term interests are to have friends in our own hemisphere, to have the respect and support of other countries. What we seem to be doing is driving them away, one by one, isolating ourselves. We, in effect, are making ourselves a Fortress America—it’s not the Soviets doing it—it’s us. If you assume that the Soviet Union wants us isolated in our own hemisphere, wants us in effect to become a lone fortress, we are helping them in every possible way. That’s what I mean by self-defeating.

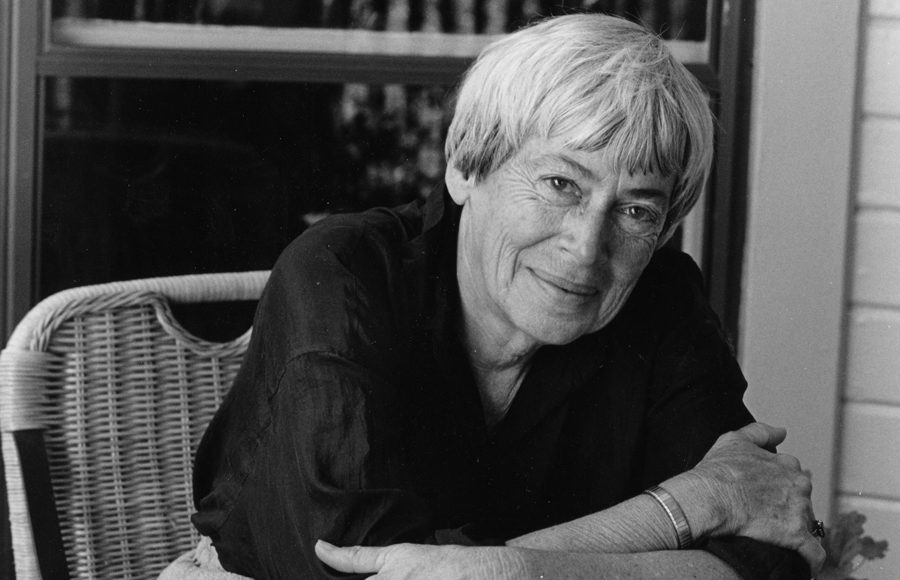

Ursula K. Le Guin, interviewed by Choire Sicha, 2015

Ursula K. Le Guin, interviewed by Choire Sicha, 2015

You want strong opinions? Anybody can write. You know, one of my daughters teaches writing at a community college. She teaches kids how to put sentences together, and then make the sentences hang together so that they can express themselves in writing as well as they do in speaking. Anybody with a normal IQ can manage that. But saying anybody can be a writer is kind of like saying anybody can compose a sonata. Oh, forget it! In any art, there is an initial gift that had to be there. I don’t know how big it has to be, but it’s got to be there.

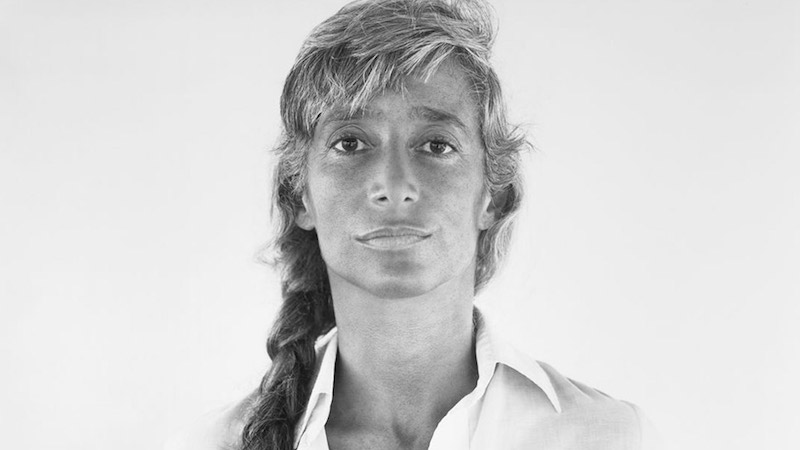

Chris Kraus, interviewed by Leslie Jamison, 2017

Chris Kraus, interviewed by Leslie Jamison, 2017

I guess I’m really committed to telling the truth in writing. It’s a corny idea, but I think that’s what writing does. It tells the truth about something. And that’s the pleasure, relief, of reading it. You realize, I’m not alone. But to tell the truth about something, you have to come up with the facts. Like a deposition. I love reading legal writing.

. . .

I started writing so late and put it off for so many years. When I finally started, I felt like I had nothing to lose and might just as well tell the truth. Do you feel when you’re working on something, that you’re kind of calibrating your whole self towards a point of being able to write it? The material stays in your body a long time before you start working. The novels I wrote took a long time, not because I was rewriting things, line by line, but because I had to find the right place to write from. As soon as you find that, you’re there.

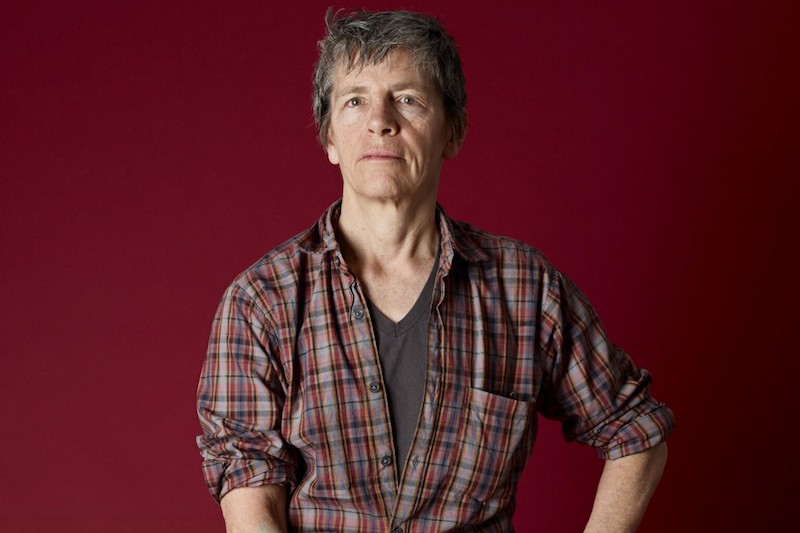

George Saunders, interviewed by Zadie Smith, 2017

George Saunders, interviewed by Zadie Smith, 2017

On Lincoln in the Bardo:

GS: From the beginning, I actually had it in mind not to write a novel. I’d kind of gotten past that point where I felt bad for never having written a novel, even to where I felt really good about it, like I was a real purist. And then this material was around and I approached it, but almost warning it, like, “Do not try to bloat up on me because we’re not doing that; we’re not writing a novel. We’re not going to suspend all the usual rules of composition that I have accrued over the years just to get past the 130-page mark.” There were several points where I would kind of turn to the book and say, “Get thee behind me.” I don’t think real novelists do that. But I make a distinction between prose that’s very efficiency-minded (like, the minimum I can get away with), versus loosening the screws and letting the words spill out beautifully and so on. I don’t really write beautifully naturally, unlike some people in this conversation. I don’t feel like I have the intelligence to really inhabit a consistently high level of prose. I have to really squeeze it to make it into something. It blew my mind, reading Swing Time, that I could take any sentence in the book, and it was one of the most beautiful sentences written in English, and you grafted all those sentences into this incredible, multi-continent, epic. Such a vast and expansive book. It made me a feel a little bit like when I used to read David [Foster] Wallace. Like, “I can’t play that game. I wish I could, but I can’t do it.”

ZS: The young people have a phrase for this now, which is “slay in your lane.” [both laugh] That’s a very important principle of writing. You have to work out what it is you can’t do, obscure it, and focus on what works.

Zadie Smith, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2012

Zadie Smith, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2012

On NW:

If I’m honest with you, I feel that this book is the first book that I’ve really written as an adult. For a lot of people this would be their first novel. I’m 36. It happens that I wrote three books as a very young person. I don’t think it’s uncommon. There are a lot of British writers who started young, from Dickens to Amis to McEwan. But they were much more sure of themselves as young writers than I was. Your mid-thirties is a good time because you know a fair amount, you have some self-control. I knew my own mind a bit more. And I stopped trying to please people.

. . .

I got a little tired of this idea of an authorial voice of complete knowledge or perfect wisdom. I got really tired of being in readings and having people much older than myself saying, “Oh, you’re so wise, you’re so full of wisdom.” But I don’t know anything! What you’re reading is an imitation of what wisdom sounds like. And so I got very tired of that voice, because it really is just a voice. There are other ways to demonstrate the fact that you’re pretty much put down midstream. It’s like you’re being thrown and you have to make it up as you go along. I read a lot of existentialism when I was writing this book, but it doesn’t have to be high theory. You know it yourself. You’re so profoundly inconsistent from one moment to another. The shock of your life, for instance, is to be shown a letter you wrote from five years ago. You usually can’t even recognize the voice. I wanted to express that feeling of self-alienation or the sense of not really having a self at all. For so many novels, it’s like they’ve taken characters and got them on a pin. The point is to make them squirm, to ridicule them, to judge them, and pronounce this final conclusion, which is usually a faux liberal “Ahh . . . But no one knows anything in the end.” Full of judgment, full of opinion, full of certainty, and I just found it quite suffocating.

Gabriella Demczuk

Gabriella Demczuk

Ta-Nehisi Coates, interviewed by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 2017

CNA: You write a lot about being defiant. You’ve said that you don’t have faith; instead you have defiance. But in the end, you realize that even defiance won’t save you. I think your writing is defiant, and you write about white people liking your writing. The people you wrote the truth about suddenly turned around and named you as a favorite writer. I wonder how you feel about that? You know how often people of color are accused of being sellouts.

TC: Sellout! Well, I think so much of writing is about how you deal with failure. I meet a lot of young people who have the talent and the work ethic to write. A lot of them are really intelligent and have succeeded for much of their lives. But writing is different: you have to fail in order to move forward. You can’t smart your way out of it. You can be smart as hell and it just doesn’t matter. You’re going to fail. Do you know what I mean?

CNA: Yup.

TC: I think that deters a lot of people. But even before I became a writer, I accepted the possibility of failure in my daily life. It was just the fact of my life: I could try to be a good person, but pretty much everything else that was going to happen to me out in the world was beyond my control. And it probably was not going to end too well. That was my thought. And even if that was a place I didn’t want to be, that was my home, that’s where I lived. Even after I started writing for The Atlantic, I remember just waiting for everything to go wrong at some point. And it didn’t. And it probably won’t. So what happened was, although I was very much prepared for failure, I was totally ill-prepared for success. I wasn’t prepared for masses of white people, as you say, to read my work. Now, if you write for The Atlantic, the majority of the people reading your work are going to be white. That wasn’t what I was shooting for when I set out to be a writer. When my first book [the 2008 memoir The Beautiful Struggle] came out, I drew 20 or 30 people at a reading in San Francisco, and I recall thinking, “This is awesome, this is perfect. I have a group of people who want to hear what I have to say.” Then, when Between the World and Me came out, I drew almost 3,000 people to a reading in Seattle, and that was not at all what I pictured. I know these are things that a lot of people would cut off their right arm to have, but I wasn’t prepared for it at all.

Tom McCarthy, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2012

Tom McCarthy, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2012

CB: I hope this doesn’t sound strange, but Remainder‘s obsessive reenactments, which involve even the smallest quotidian movements, reminded me almost of how fetishists treat sex. Now you do this to me, now I do that to you, now you put your foot here…there’s this over-rehearsed exercise to the act of sex.

TM: Oh, yeah. There’s a huge sexual element. Someone asked, “Why is there no sex in the book?” My answer is, “It’s all sex.” The whole thing is sex. I was looking at Sade when I was writing it. I read it when I was about 20, but I hadn’t reread it, and 120 Days of Sodom is all about reenactment. There are four libertines, four perverts, who are incredibly wealthy and they kidnap all these teenage kids. 11-, 12-, 14-year-old kids. And they take four high-class prostitutes with them to this castle, this room, and he meticulously describes the layout. It’s a room with four alcoves. And one libertine sits in each corner. The kids go on the floor, and a prostitute stands in the middle and starts telling stories. One time, she’s fucking these three guys, one time, blah blah blah. The rules are, at any point any of the four libertines can go, “stop, that bit is good, let’s do it.” They use the children as extras, and they reenact it. They also modulate it. They say, “It would be even better if, instead of four of us, there would be six,” almost like an algorithmic set of variations. So there’s this space within narrative, where you can move from being a passive listener to an active doer, or a re-enactive doer. And this is a move into violence. I think that logic is central to Remainder. It’s a sadomasochistic sex game all the way through.

Renata Adler, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2014

Renata Adler, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2014

RA: When Speedboat came out, I had just entered law school at Yale. I had meant to go to law school after college. And after the impeachment inquiry, I was interested in what evidence is to a lawyer as opposed to what it is to a journalist. I thought a journalist should know the way through that. I guess I didn’t know what was going to happen when Speedboat came out. I thought, I better be in law school, because who knows whether anyone will like it or not.

CB: Obviously, fiction writing is very different from journalism. But Speedboat is like your nonfiction, in that each sentence has so much in it. There’s no skimming or sweeping over the surface. Speedboat is a novel that demands constant focus.

RA: I didn’t know how else to get from here to there. It doesn’t really get you from here to there either, but it gets you from somewhere to somewhere. It just came out that way.

Lynne Tillman, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2014

Lynne Tillman, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2014

On women and essay writing:

Maybe I could say this, which is probably a gender-political statement. I think those women who get themselves to write essays, it’s not an easy thing to do because as women, you’re not encouraged to think; you’re encouraged to feel. This is a broad, broad statement. So I think those women who go out on a limb and publish essays are highly conscious of how they are writing their opinions. That’s an integral part of what they’re saying and how they’re going to say it because sitting on their shoulder is an albatross that’s been telling them, “We don’t really want to hear…” I’ll tell you something. When I finished American Genius, A Comedy, one of the editors who rejected it, the only female editor to whom it was given, said about the novel, “I don’t know what Lynne is trying to teach.” I believe it’s not something she would have written to a male novelist who already had four novels out and a few other books. So the idea a writer who is a woman has something to say or is even polemical or whatever—you’re in a tougher situation, and I think those of us who’ve jumped in there are really watching our P’s and Q’s very carefully. I don’t mean holding back. I mean the opposite: going for it. You’re not going to shut me up, and I’m going to say it as best I can.

Toni Morrison, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2012

Toni Morrison, interviewed by Christopher Bollen, 2012

In Home, I wrote from a man’s point of view. I had never really done that seriously until Song of Solomon. I thought, “What are they really like? What do they really think?” My father had died shortly before, and I remember saying, “I wonder what he knew.” And then I just felt relief, that, at some point, I would know, because I’d asked the right questions of him, and that it would come. And in fact it did. I’ll tell you what helped: black male writers write about what’s important to them or their lives, and what is important to them is the oppressor, the white man, because he’s the one making life complicated. Then I noticed that black women never do that. In the ’20s, they did, but I mean contemporary—and I wasn’t interested in it. Suddenly if you took the gaze of the white male—or even the white female, but certainly the male—out of the world, it was freedom! You could think anything, go anywhere, imagine anything . . . There was no longer the problem of looking through the master’s gaze. With that gaze, you’re always reacting, proving something. So not having to do that . . . I think one of the reasons I’m so thrilled with writing is because it is an act of reading for me at the same time, which is why my revisions are so sustained. Because I’m reading it. I’m there. Intimacy is extremely important to me and I want it to be extremely important to the readers, too.

Eileen Myles, interviewed by Adam Fitzgerald, 2015

Eileen Myles, interviewed by Adam Fitzgerald, 2015

When people decide to talk publicly about poetry as an art form and how it’s received, they often get very abject about it: “Nobody reads poetry,” and then a thousand people write back, “No, we read poetry.” There’s an abundance of this negative preaching to the choir, and it’s very similar to the experience I’m having. It’s like poor Eileen, you probably don’t know this person, but she’s really great, and now she has been rescued by the mainstream. People can’t let go of the unit of the poet or the unit of the privacy of their own reception, and that’s the thing that’s weird—the way I keep hearing about all these unknown years in the darkness I had with independent small presses, but no, that’s how poetry is known. It’s like forever—it’s many, many little rooms making a big room. That’s the nature of the art form, and that’s what’s happening for me now. It’s just the little room got big.

Hanya Yanagihara, interviewed by Adam Leith Gollner, 2013:

Hanya Yanagihara, interviewed by Adam Leith Gollner, 2013:

You know, I’ve never really understood the desire [for immortality] myself. I know you were raised without religion and so was I. The idea of both wanting to live forever in some form and wanting to stay young forever just sounds exhausting. It’s one of those desires that people think they want but when you actually stop to think about what it actually means, it’s really awful. One of the reasons that life is bearable is because it’s going to end soon. One of the main concerns of fiction is how do we make a life of 85 years or so meaningful. If you start asking how do we make life meaningful and life never ends, then you get into sort of these terrible sort of metaphysical quandaries and it gets really, really bleak looking.

Miranda July, interviewed by Carrie Brownstein, 2015

Miranda July, interviewed by Carrie Brownstein, 2015

On fantasy and gender in The First Bad Man:

Much of the book is about the fantasy world and about how gender is up for grabs in your own secret fantasy life. Like, people who would not be using the word gender or thinking about gayness or trans-ness may actually, without even thinking about it, be not their own gender in their inner world. I think that’s actually so normal, because female sexuality is sold to all of us. It doesn’t just reach the eyes of men. You might not care about the idea of boobs or jugs or whatever, but it could impact your inner sexual life. So I was trying to go as far as I could with exploring that, without ever using the politicizing words that we’re used to. I have a character who wouldn’t know or care about any of those words who is wildly exploring that.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.