Now, I do not believe that my children will pack up their little clothes and their small treasures in colored bandanas and set off, trudging sadly down the road out into the cold world—I do not really believe that my children will run away from home if Mommy is not up in time to give them breakfast, but this morning the house was suspiciously quiet, and when I cried out “Laurie?” and then “Jannie? Sally?” there was not even an echo to answer me. My husband stirred uneasily and I snarled at him, rolling out of bed and racing into the girls’ room, saying “Jannie? Sally?” in a voice which became more urgent as I perceived that they were not there, but that they had most certainly been there for some space of time after arising; the toys were out of the bookcase and a fort of some kind had been built with dresser drawers in one corner of the room; Jannie’s box of very small glass beads had been broken open and the beads scattered around thoughtfully near to the door so that, barefoot, I managed to step on several thousand.

As a last heartbreaking touch—a tender gesture for Mommy, no doubt, and probably performed just before the final exit into the world—both beds had been made, crookedly and with the sheets hanging, but still made, with the spreads put on. In Laurie’s room, The Boy’s Book of Baseball Stories lay open on the bed, and Barry, who after nearly nine vivid months of life had developed a kind of patient cynicism about his family, was lying in his crib talking to himself and playing agreeably with Laurie’s hairbrush. I absent-mindedly picked up Laurie’s pajamas, which were sprawled on the floor, and looked into them vaguely, saying “Laurie?” Since his dirty socks and dirty shirt and bathing trunksand riding boots were on the floor I could see no reason for hanging up his pajamas, and dropped them back onto the floor and said to Barry, “Where is Brother?” He stared at me, and then smiled.

Followed by Barry’s sudden wail, I went padding from step to step downstairs and into the kitchen, where I was suddenly made aware of my optimistic conclusion the night before that I would leave the dinner dishes and do them in the morning. “Laurie?” I said. “Jannie? Sally?” There were three cereal bowls on the table, two empty and one half empty, and, glancing at the cereal boxes where they sat high on the shelf, I reflected briefly on the magical capacities of children who are hungry and relieved of the pressing assistance of adults. I decided that I could not go out hunting for my children until I had clothes on, and went back upstairs to dress. I had brushed my teeth and combed my hair and was looking for a clean handkerchief when I heard the clear sweet voice of my long-lost daughter Sally. “Mommy?” she was saying in the kitchen, “Mommy has gone to Fornicalia to live. Where my grandma lives, grandma. Would you please like some breakfast?”

Concluding, and rightly, that she was talking to the milkman, who needed urgently to be told that he must leave three quarts of milk instead of five, and a dozen eggs, I went to the head of the stairs and shouted, “Sally? Tell him to leave eggs and three quarts. Then stay exactly where you are until I come down.”

I slammed the dresser drawer shut, hoping it would wake my husband, slid into my shoes, and raced downstairs to find Sally, who has a kind of literal mind, frozen halfway between the door and the table. “Can I move now?” she asked, as I came to a stop, “move?” There were five quarts of milk on the table, and three dozen eggs. “Sally,” I said helplessly, “where have you been?”

Sally, who was then almost four years old, has always been very pretty. Any time I am prepared to spend an hour or so working on her, she is very lovely indeed, although her general appearance is of a child barely kept in a state of minimum human cleanliness by the most stubborn determination. Her hair was not cut short until she was six, so that summer it was still long and curly; since this particular morning she had been on her own for several hours she was recognizable largely by the voice and by the horrible doll she was carrying. She had chosen to put on a sunsuit, which would have been perfectly reasonable if she had not put it on backward; her hair was not able entirely to conceal the condition of her face, and from where I stood it looked very much as though she had gotten a lollipop from somewhere, because there was a lollipop stick wound in one curl. “Where have you been?” I asked again.

“Out,” she said inconclusively. “I been visiting, visiting.” Her odd jangling manner of speech had never annoyed me more, and I said sharply, “Visiting where?”

She waved. “Around,” she said.

“Where is Jannie? Laurie?”

“Laurie is on his bike. Jannie got eaten by a bear, eaten.”

This was so close to my guilty expectations that I went nervously to the kitchen door and looked out; there were no bears but at least part of Sally’s general appearance was explained by the impressive line of mudpies on the back step. Following a reasonable train of thought, I asked, “Did you have breakfast?”

“I had it at Amy’s house, Amy’s.”

Amy’s mother was one of the sweetest people I had met that summer. Her children were always spotless, and they were fed at correct times in an immaculate kitchen. I had never heard Amy’s mother raise her voice to her children and she always seemed to have time to make her own clothes. “You would go to Amy’s,” I said.

“Well, I told Amy’s mother that I did not have any breakfast, breakfast, because my mommy did not wake up and give it to me, mommy. And Amy’s mother said I was a poor baby, baby, and she gave me cereal and fruit, cereal, and she said there, dear, and she gave me chocolate milk and I did remember to say thank you, remember.”

I made a mental note to stop over later and tell Amy’s mother laughingly that Sally had certainly fooled us, hadn’t she, because was right here making breakfast and Sally had just run out and I had spent hours looking for her and . . . “I told Amy’s mother you were gone away to Fornicalia,” Sally said, seating herself at the table before her half-finished bowl of cereal. “Laurie got me this cereal but he put on too much milk and I went to Amy’s.”

She seemed satisfied that she had given me a reasonable account of her morning, and I said “California” absently as I began to clear dishes out of the sink and stack them. “Hickory Dockery Dick,” Sally said musically. “Why did they come home wagging their tails behind them, tails?”

By half-past eleven I had coffee making and had located Jannie (breakfast at Laura’s house, scrambled eggs and orange juice and toast because Jannie’s mother was still asleep because Jannie’s mother had not come home until way, way late last night) and had had word of Laurie, who called to say that he was at the stables helping water the horses and would be back in a little while for lunch. “I see you finally got up,” he remarked over the phone. “Yeah,” I said.

I had fed Barry and put him in his playpen, and was feeling a little bit less like the delinquent mother whose children are found begging in the streets. Sally told me a long story about an elephant she and Amy had encountered, which asked them civilly the way to the zoo, zoo, and gave them each a piece of bubble gum, a delicacy ordinarily forbidden Sally, but I had to let her keep it because it was a present from an elephant. By the time my husband came stomping downstairs I was sitting at the kitchen table drinking coffee and smiling maternally at Sally; I gave my husband another smile of patient, tolerant understanding, and asked him sweetly if he would care for coffee? He nodded, and sat down at the table, but he jumped when I lifted the frying pan. “Eggs?” I asked him, and he shook his head no.

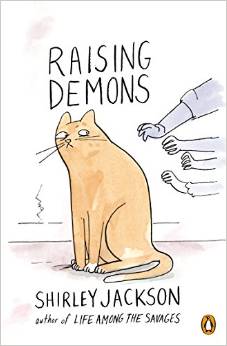

From RAISING DEMONS. Used with permission of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2015 by Laurence Hyman, Joanne Schnurer, Barry Hyman, Sarah Webster.