The richest stream of American punk rock is actually Mexican-American punk rock. It can be traced directly back to two self-taught wunderkinds whose lives collided: Jeffrey Lee Pierce, a second-generation Mexican (on his mother’s side) from El Monte in East LA, and Kid Congo Powers, with two Mexican parents, from seven miles east, in La Puente.

Their separate paths were parallel. As a teenager, Jeffrey Lee was the president of the Blondie fan club. Kid Congo Powers was the president of the Ramones fan club. They’d each gone alone to New York riding Greyhound, to check out the No Wave scene. Back at home in LA, Jeffrey Lee wrote for the music magazine Slash. Kid wrote the newsletter for legendary LA band the Screamers. These two kindred boys met outside a Hollywood punk club one night in 1979.

Kid was attracted to Jeffrey Lee’s look: white vinyl trench coat, white cowboy boots. They bonded over a shared hunger for wild notes of influence not to be found locally. Jeffrey Lee told Kid he was starting a band, and that Kid could be the singer. “I can’t sing,” Kid said. “Then you’ll play guitar,” Jeffrey Lee said. “I don’t play guitar,” Kid responded, apologetically. “I’ll teach you,” said Jeffrey Lee. He gave Kid a Bo Diddley record and a slide guitar, tuned to an open E, along with a cassette of mood music: Delta blues, gunfighter ballads, Ornette Colman, and what Jeffrey Lee summarized as “lowlife Amerika.”

They formed a band. Jeffrey Lee sang. He was a savant vocalist with a spine-tingling caterwaul. He looked, as he sang on “Love of Ivy,” like an Elvis from hell. Kid Congo, on slide guitar, wore a gold blazer from Lansky Brothers in Memphis, where Elvis himself had shopped.

I was twelve when the Gun Club’s first record, Fire of Love, was released, in 1981. I had an older brother and lived in a city (San Francisco) with a punk scene. I knew this music was cool, and this singer too, whose vibe was Robert Mitchum in Night of the Hunter: an evil preacher in black leather, but with hair bleached to look like Deborah Harry’s.

The first four Gun Club records still remind of me of adolescence, of the desire to break something, and/or be destroyed, a destruction that for a young person transmits as hope, because it is energy. Of all the Gun Club’s records, Mother Juno, released in 1987, when I was 18, shocks me most, with its beauty and depth. I listen to it still. It’s lush and dreamy, and it’s also hard. It’s rock and roll. I remember the day I bought it. I was in college and went to Rasputin Records on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, brought it back to my apartment and started playing it over and over, mostly the second side (this was the era of vinyl). Even the wine-fuchsia hue of the album sleeve envelopes me in feeling from that time. Not the context of the time (confusion, as a person with no idea why she was in college), but a feeling of wild possibility in the music itself, which obliterated context.

He was a savant vocalist with a spine-tingling caterwaul.The unique sound of Mother Juno among Gun Club records is partly to do with the fact that Robin Guthrie, of the Cocteau twins, produced it. It was recorded at Hansa Studios in Berlin. “We blew people’s minds,” Kid Congo later said about that record. They wanted a sound that linked back to their origins. East LA. Fierce music you’d hear from garages, while people worked on cars. By coincidence or not, Jeffrey Lee had stopped bleaching his hair, at that point. For the first time in his life as a musician, he looked Latino. Perhaps the secret power of Mother Juno is intertwined with a determination to transcend stereotyped ideas about who owns what culture, what music.

The “hit” from the album, “Breaking Hands,” has a jangly, life and death 4AD shimmer that floats around the edges of Kid Congo’s slide guitar like a moving gallery of luminous colors reflected from a mirrored ball. Jeffrey Lee’s voice is a yearning vibrato in a stripped-down atmosphere. The album has a grand and echoing but raw, bare sound. Hansa studios is an old ballroom. After I saw photographs of it—a cavernous room with an ornate ceiling, parquet floors and huge chandeliers—I heard that room in the album.

I realize, writing this, that I’ve been listening to the song “Breaking Hands” for 33 years and it never bores me. It never gets old. I love the whole record, but my two other obsessively repeated numbers are “Yellow Eyes,” which features guitar playing by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ Blixa Bargeld, and “Port of Souls.” I don’t know what to say about “Port of Souls” except it holds in it some secret that I’ve convinced myself has to do with me: a secret I possess, about me, and that is eternally kept from me. I listened to it repeatedly when I was writing my last novel, The Mars Room. I even thought about titling the novel “Port of Souls.” But the words alone are not enough. It is the music, the layered guitars and cool and mysterious feedback and Jeffrey Lee’s voice that transports. When I listen to the song now, I remember what I felt the first time I heard it. Which is to say, I remember what it felt like to want to exist only and totally in the present tense.

Jeffrey Lee Pierce died from drugs and alcohol in 1996, at age 37. For a while I held onto this dumb idea that he died on the fourth of July, as if to cure my disdain for patriotism by recuperating it with this sad date. But it isn’t true. Recently, I was talking to an old boyfriend about Jeffrey Lee, of having seen him play live in 1993, and how sad he seemed, how unhealthy he looked, in a too-small blazer, a Mao cap pulled down above his swollen face. This old boyfriend said, “Gosh, I didn’t even remember you were a Gun Club fan.” A few years ago, this ex-boyfriend had a serious motorcycle accident that affected his memory. So he’s excused. Otherwise he never would have forgotten such a thing.

________________________________________________

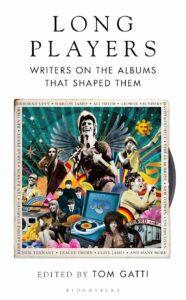

Excerpted from Long Players: Writers on the Albums that Shaped Them, edited by Tom Gatti. Copyright (c) 2021 by Rachel Kushner. Used with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. All rights reserved.