Getting to Know an Author Through Their Home

Amy Belding Brown on Visiting the Houses of Emily Dickinson, Louisa May Alcott, and More

I can’t remember not wanting to be a writer. By the time I was in third grade, I was thinking up stories instead of paying attention to my arithmetic lessons. When I was older I began to think about the people who wrote the stories I loved. I wondered how they lived and where they wrote. So maybe it was inevitable that, as an adult, I’d seek out the homes of writers whose books I loved. Since then I’ve become an enthusiast of house museums. Often humble as museums go, the best of them allow the public to glimpse what life must have been like for those who inhabited them. Thanks to the efforts of preservationists and devoted fans, these museums make fascinating destinations for anyone who loves reading.

Here are a few I’ve visited:

The Orchard House in Winter

The Orchard House in Winter

Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts. As a girl, I read and loved not only Little Women but all of Alcott’s children’s books. Twenty years ago I had the job opportunity of a writer’s lifetime and was employed there as a tour guide and educator. During that time I was writing my first historical novel, Mr. Emerson’s Wife, and the Concord characters became so real to me that I often felt I might bump into them in the next room or hear them knocking on the front door. Not as strange as it sounds, since the Emersons, Thoreaus and Hawthornes had all had socialized with the Alcott family in the rooms I dusted in the mornings before taking visitors through. Lidian Emerson, my protagonist, had attended Bronson’s School of Philosophy in the building (designed and built by Bronson) that still stands on the property. The sense of immediacy was palpable and the experience provided me with vivid, necessary details for my novel. Orchard House has a special place in my heart and of all the author homes I’ve visited, it remains my favorite. (But I admit I’m biased.)

The Homestead

The Homestead

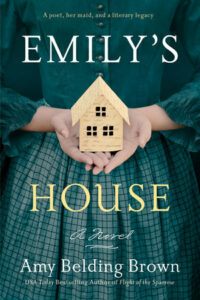

The Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts. I feel as if Emily Dickinson has always been in the backdrop of my life. I have many linkages to her, including through my family tree. My grandmother lived in nearby Northampton and when our family visited her, we often drove out to Amherst and passed the handsome brick home my parents identified as the famous poet’s home. In those days it wasn’t yet open to the public, and it was many years before I actually visited the house. The quiet elegance of its rooms left me with a contemplative feeling that drew me back to visit several times—and eventually inspired my latest novel, Emily’s House, in which the Homestead is almost a character itself. The museum is in the process of restoring the house to the way it looked when Dickinson lived and wrote there. They’ve recently reconstructed her beloved conservatory, and restored the wallpaper in her room. So it continues to be an exciting place to visit, and I hope to return often.

The Evergreens

The Evergreens

Next door The Evergreens, home to Emily’s older brother and her beloved sister-in-law Susan, is also open to the public. Emily spent many happy hours there before she became completely reclusive. The house never passed out of the family before becoming a museum, so most of the furniture and fixtures are original. The decor reflects Susan Dickinson’s taste and is notably more fashionable for its time than The Homestead.

The Mount in Lenox Massachusetts. In my twenties and thirties I read and loved all of Edith Wharton’s novels, but it wasn’t until many years later that I had the chance to visit the lovely estate in the Berkshire Hills where Wharton lived and wrote. While there I learned that Wharton was not only a writer but an interior decorator and amateur architect and that she actually designed The Mount. It’s a light-filled, spaciously elegant place, with striking formal gardens that should not be missed. I felt especially privileged walking into the room where she spent mornings writing in her bed.

School of Philosophy

School of Philosophy

Fruitlands in Harvard, Massachusetts. This is one of the many homes where Louisa May Alcott lived when she was a girl. This simple farmhouse represents a formative and possibly traumatic time in Alcott’s life, when her family participated in a communal experiment which nearly resulted in starvation. Though located in a beautiful setting, its stark furnishings and the unconventional living arrangements of its inhabitants, provide new insights into the experiences that shaped the young writer. (On a side note, it was in the Fruitlands gift shop where I first encountered Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative, the book that inspired my novel Flight of the Sparrow.)

The Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut. Samuel Clemens had this extraordinary 25-room house designed and built for him after he achieved broad popularity, and he later claimed that his years there were the happiest and most productive of his life. It’s probably the most dramatically luxurious home I’ve ever been in. With their mahogany woodwork and furnishings, many of the rooms are stunning in their extravagance. Especially memorable is the graceful beauty of the conservatory off the library, Twain’s massive “angel bed” and the billiard room at the top of the house, where Twain wrote. I could almost smell his cigar smoke when I stepped into the room.

Louisa May Alcott’s Desk

Louisa May Alcott’s Desk

The Wayside in Concord, Massachusetts. Sometimes called the Home of Authors, the Wayside was the name given to the house by Nathaniel Hawthorne and his wife, Sophia Peabody, when they bought it in 1852. Like many readers over the years, I was captivated by Hawthorne’s haunting The Scarlet Letter, and revisited it when researching Flight of the Sparrow. It’s a fascinating house, with lots of intriguing nooks and crannies, including a tower/cupola room which Hawthorne had built so he could lock himself away to write. The Wayside is located next door Orchard House and prior to the Hawthornes, the Alcotts had lived there for seven years. After Hawthorne’s death, the house passed to yet another writer— Harriet Lothrop, aka Margaret Sidney, author of The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew.

__________________________________

Emily’s House by Amy Belding Brown is available now from Berkley.