Queer Black Poets Since the Harlem Renaissance: A Reading List

From Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson to Juliana Huxtable

This Spring, Nepantla: An Anthology for Queer Poets of Color (Nightboat Books, May 2018) was released in collaboration with Lambda Literary. The anthology is the first of its kind in the English speaking world, and spans nearly 100 years of literary history. It pushes against the historical and biographical erasure of queer poets of color from too many literary classrooms.

Below is a timeline of contributions by queer and trans black poets since the Harlem Renaissance. This article is focused specifically on the literature of queer black poets because American racism was built from the start off of anti-blackness and anti-indigeneity. Many of these poets were not only visionary writers, but also freedom fighters, survivors, legends, and proof that the vital poetry of queer black artists has shaped the world of American letters. All are featured in the Nepantla anthology.

Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935)

Read “You! Inez!” by Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson

Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson lived very much in the recent memory of slavery’s aftermath. Born free in New Orleans, she was part of the first generation of black Americans not born into slavery in the South. Nelson was bisexual, mixed race, and wrote across multiple literary genres. At a time when very few Americans attended college, she graduated from Straight University in 1892. Her first book of poetry and short stories, Violets and Other Tales, was published when she was 20. Alice was briefly married to Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of the first prominent black poets recognized in American letters who received much critical attention in the late 19th and early 20th century. But Dunbar was abusive, and Nelson ultimately left. She is also the author of The Goodness of St. Rocque and Other Stories (1899) and was an influential figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967)

Read “Warning” by Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes is undoubtedly the most prominent poet in our cultural memory of the Harlem Renaissance, which is often thought of as the first big movement in black American poetry, though this is most definitely not where black literature begins in the U.S. Hughes was heavily influenced by jazz, and his literary influences included Walt Whitman and Paul Laurence Dunbar. During his lifetime, Hughes was also published as a novelist and playwright. His work has been translated into German, French, Spanish, Russian, Yiddish, Czech, and more. While his depictions of working class black life were heavily criticized during his lifetime, they ultimately ultimately broadened the subjects about which people could write, and how.

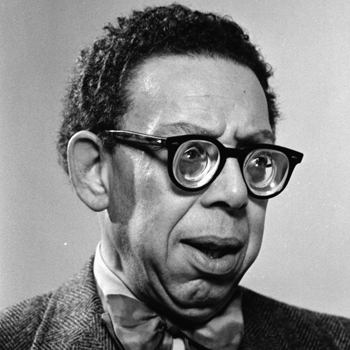

Robert Hayden (1913-1980)

Read “Those Winter Sundays” by Robert Hayden

From 1976 to 1978, Robert Hayden was the first black writer to serve as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, what is today called the Poet Laureate. Though Hayden was married, he privately struggled with his bisexuality. During the Black Arts Movement, Hayden was often criticized for wanting to be viewed as an American poet first, rather than a black poet, which cost him much popularity at the time. But Hayden’s poems were still very rooted in the black American experience, and he often wrote of black social figures like Malcom X and Harriet Tubman. As a child he lived through the Great Depression and had been bullied for his severe myopia; that experience is what ultimately led him inwards, towards poetry. In his poem “The Tattooed Man,” Hayden writes, “All art is pain. Suffered and outlived.”

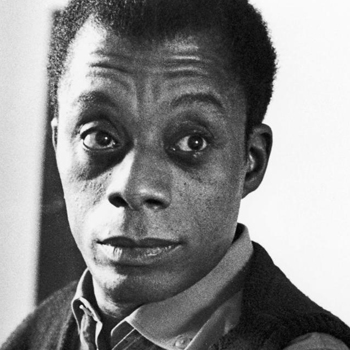

James Baldwin (1924-1987)

Read “Untitled” by James Baldwin

Baldwin was a brilliant prose writer, poet, and activist who lived between two great black literary movements: the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement. His 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room, about an affair between a bisexual American expat in Paris and an Italian man facing execution, was one of the first books to bring Baldwin into the literary spotlight. Baldwin was known for what Orde Coombs called in the New York Times Book Review “his insistence on removing, layer by layer, the hardened skin with which Americans shield themselves from their country.”

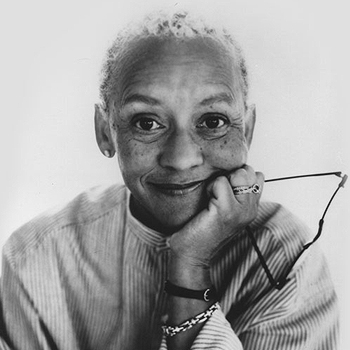

Audre Lorde (1934-1992)

Audre Lorde’s major works were largely published after the Civil Rights Era, though she published in journals throughout the 1960s and participated in both the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements. Her first book of poems, The First Cities, appeared in 1968. She is most notably the author of The Black Unicorn: Poems (1978), Zami: A New Spelling of my Name (1982), and Sister Outsider (1984). Her influence on black feminist and queer communities runs deep. Today, Audre Lorde quotes still fill t-shirts and signs at protests. In The Cancer Journal, she wrote, “When I dare to be powerful, to use my strength in the service of my vision, then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.”

Nikki Giovanni (1943- )

Read “BLK History Month” by Nikki Giovanni

Nikki Giovanni is a prominent figure of the Black Arts Movement. The poets of the Black Arts Movement were often very politically and rhetorically centered in their work. Giovanni now teaches at UVA and has been awarded over twenty honorary degrees from universities around the country, along with numerous literary awards. She is one of the most celebrated living poets in the United States. As a Publisher’s Weekly review of Giovanni’s collected poems put it, her “outspoken advocacy, her consciousness of roots in oral traditions, and her charismatic delivery place her among the forebearers of present-day slam and spoken-word scenes.”

Essex Hemphill (1957-1995)

Read “American Wedding” by Essex Hemphill

Hemphill was one of many people who died too soon in the midst of the AIDS crisis and at the peak of his career. A performer of spoken word poetry, he was a leader in Washington DC’s literary community. His book Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry (1992) won the National Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual New Author Award, and he also edited the anthology Brother to Brother: New Writing by Black Gay Men (1991), which won the Lambda Literary Award. He was known during his lifetime as a fierce political advocate for issues affecting the queer black community, including HIV/AIDS.

Carl Phillips (1959- )

Along with other black poets such as Major Jackson, John Keene, Tracy K. Smith, Natasha Trethewey, and Kevin Young, Carl Phillips was an important part of the Dark Room Collective. This collective formed after the funeral of James Baldwin in 1987, where two of its founders Thomas Sayers Ellis and Sharan Strange were moved to further cultivate black literary community. It began as an intergenerational reading series that hosted and cultivated the work of black poets of various aesthetic movements. Many people affiliated with the Dark Room Collective have become leaders of the poetry landscape. Phillips himself has authored 13 books of poetry and teaches at Washington University is Saint Louis. When he was a finalist for the 1998 National Book Award for Poetry, the judges’ citation read, “Carl Phillips’s passionate and lyrical poems read like prayers, with a prayer’s hesitations, its desire to be utterly accurate, its occasional flowing outbursts.”

Dawn Lundy Martin (1970- )

Read “The American middle class . . .” by Dawn Lundy Martin

Along with Ronaldo V. Wilson and Duriel E .Harris, Dawn Lundy Martin is part of the Black Took Collective, a group of queer black avant-garde poets throughout the United States who formed in 1999 at a Cave Canem Retreat. The group embraces hybrid forms, incorporating video and critical theory about race, gender, and sexuality into their poems. Martin is also the author of Life in a Box Is A Pretty Life, which came out with Nightboat Books; her most recent book is Good Stock, Strange Blood ( 2017). She currently teaches at the University of Pittsburgh where she co-founded, with poet Terrance Hayes, the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics. Fanny Howe described the poems in Martin’s Discipline as “dense and deep. They are necessary, and hot on the eye.”

Juliana Huxtable (1987- )

Read “Working” by Juliana Huxtable

Juliana Huxtable is a DJ, poet, artist, and performer. Her first book Mucus in My Pineal Gland delves into desire, technology, pop culture, queer/trans academic theory, obsessions with simulacra, and the fraught notion of reality or authenticity; the book was released in 2017 and nominated for a Lambda Literary Award. Huxtable’s work blurs the boundaries between the literary world and visual art world. Unafraid to throw out all the rules in the guidebook, Juliana will be one of the writers leading us into the future of queer and trans literature. In a review from Jacket2, Anne Lesley Selcer writes, “Mucus in my Pineal Gland takes on media and its constituting powers in our desires and ways of seeing and being.”

Danez Smith (1989- )

Read “dear white america” by Danez Smith

Danez Smith is author of the books [insert] boy (2014) and Don’t Call Us Dead (2017), which was shortlisted for the 2017 National Book Award in Poetry. Race, queerness, police violence, and HIV/AIDS are frequent themes in their work. They are the recipient of many awards, including the Poetry Foundation’s Ruth Lily and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship and an NEA grant. Smith is also one of the founders of the Dark Noise Collective, which was named after, and influenced by, the poets of the Dark Room Collective. The Dark Noise Collective is a multi-racial and multi-genre group of artists who believe in art as a site of radical truth telling. Smith and other members of the collective have a history rooted in the Spoken Word community. Fellow members such as Fatimah Asghar have successfully ventured into mediums like screenplay writing, while Jamila Woods has gained traction as a musician.