Protests, Poverty, Politics and Civil War: On Life Before the Beirut Explosion

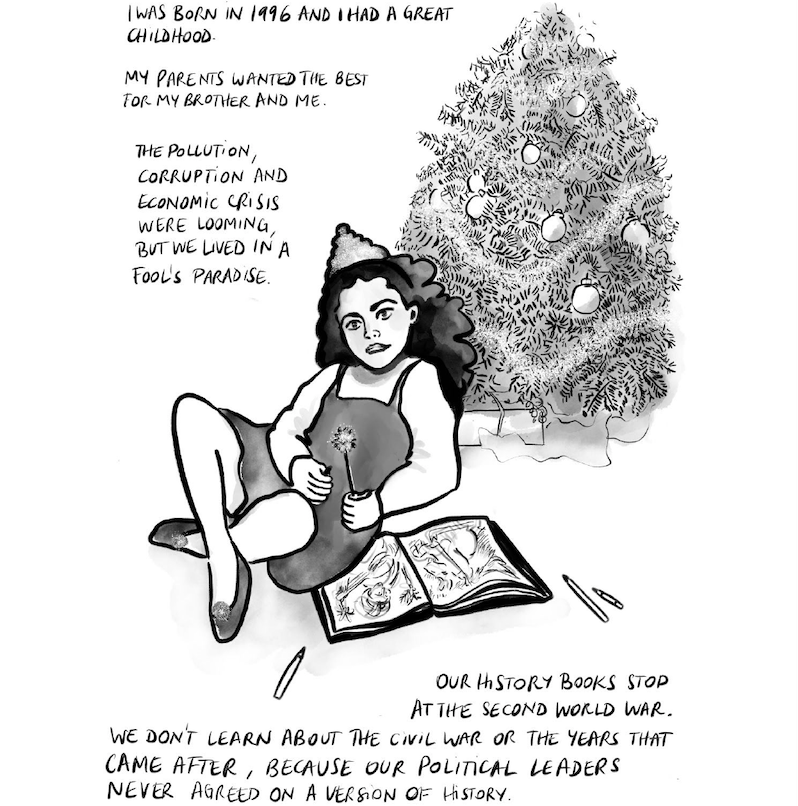

From the Graphic Novel Waiting for Normal

The following was commissioned by The Delacorte Review.

August 4, 2020

A bottle of water in my backpack, a cap on my head, and running shoes on, I set off to run some errands on this boiling August Tuesday in Beirut. Lebanon is now under a third lockdown this year. But a special lockdown: from Friday to Monday, the country is shut down, but on Tuesday and Wednesday businesses can operate normally.

On my to-do-list of this almost normal day, are all the chores I haven’t had a chance to do since I moved back from New York City two weeks ago. Getting some clothes altered by the seamstress, visiting the family, and getting a birthday gift to a friend. As I walk around the city, I daydream about how Beirut would feel like as another city. I could walk to a bus stop, or even bike around, I wouldn’t have to be stuck in traffic for an absurd amount of time to travel a ridiculously short distance. Maybe during this summer day I could sit on a park bench, enjoying the sight of all the children running around on the grass. And later in the week I would head out of Beirut, to one of our many public beaches that are rigorously cleaned by the government. Sounds normal, easy even.

A loud honk interrupts my day dream and I find myself back in a Beirut where cars park on sidewalks and pedestrians walk in the middle of the highway.

I complete my errands and arrive back home, exhausted from my morning walking. I’m supposed to meet a friend at 5:30 in Mar Mikhael, one of Beirut’s hippest neighborhoods where bars, restaurants and art galleries overlap. But at the last minute, he cancels to help out a friend. Maybe I’ll head to the gym then, before heading out to dinner.

I settle down to work at my desk. I have stories to write, and research to conduct. I think there are some peaches in the fridge so I get up and grab one. Today is the first day since I arrived back in Beirut where I’ve led somewhat of a routine. As I get up to grab something from the bookshelf I look at the peach on my desk. It starts moving.

Newly announced economic restrictions and a series of wildfires poorly managed by the government had pushed the country to the edge.

Now my desk is shaking. Is it an earthquake? It’s the first time I’ve felt an earthquake that strong in Lebanon. I hear a loud noise. Is my building collapsing? No, it sounds like a loud explosion or something falling. I look at the window to my right and I see some black residue, huge particles of dust floating in a heavy gray cloud.

What on earth is that?

And then the blast. The sound of glass shattered mixes with my mother’s screams. Did I scream too? My ear-drum feels like it’s exploded. A blinding flash appears before my eyes. A trick from my brain maybe? For a second, not even, for a millisecond, I think this is what movies describe as seeing your life flash before your eyes.

Tuesday October 22, 2019

My right wrist hurts. I know it’s because I’ve spent too much time on my phone the past week.

For the past four days Lebanon has witnessed an uprising unlike any in memory. Newly announced economic restrictions and a series of wildfires poorly managed by the government had pushed the country to the edge. Then the government tried to impose even more taxes, including on messaging services such as Whatsapp. This was too much. That night, the thawra, revolution in Arabic, was born.

I just learned that a protester died in Beirut. He is the second martyr of the thawra. I’ve spent the day on my phone. I am fuming at my government, angry that I’m so far away and cannot express my rage. I am angry that I have to go to work, take the bus, and be a civilized flat mate when all I want to do is scream at the top of my lungs that I am furious and fed up with the way this government has been treating my country for years.

I am envious of my friends who are on the streets.. I want to be there, to bang on pans, to dance in the streets I have worked so long and hard on making mine. I gave a lot of myself to adopt this city. And now that she awakens, I’m not there to celebrate it. I’m jealous of all the journalists covering the protests, the photographers immortalizing the protagonists of this movement, and the videographers recording each fire set alight, because they are lucky, they are there. But they weren’t there when we were only a dozen protesters outside the parliament a few years ago. I was.

Monday December 16

When planes approach Beirut you can usually see the whole coast through the windows on the left hand side. People look out and their excitement grows. But on my flight back to Beirut on this grim December Monday, my flight was silent as the coast appeared. Some people had their phones out. Others just looked out quietly. My heart tightened when I saw this oh so familiar sight. After months of looking at it through my screen, there it was. Lebanon. In all its splendor and misery. Birds migrate south during the cold months the same way Lebanese expatriates return to the motherland for the end of year holidays. A rite of passage for generations who have left Lebanon. But this year, the ritual was bittersweet. As of December, Lebanon is now the third most indebted country in the world, nearly a quarter of its population lives below the poverty line, and its national currency has so far lost twenty-five percent of its value.

In the tiny elevator on the way out, my mom confessed, “It breaks my heart to do this.”

It was not a warm welcome home. Nonetheless, my mother was at the arrivals gate to welcome me with arms wide open. On the ride home, I tried to catch glimpses, remnants of the protests, or some sign of revolution going on somewhere. It would have to wait.

On this winter day, Beirut seemed normal.

Thursday December 19

My mother asked me to go with her to the serraf, the money changer. The Lebanese Pound was fixed at 1500 to the US dollar in 1997, when both currencies became interchangeable. That was, until 2019. For the past few years, economists have warned of a collapse of the Lebanese Pound; the thawra was a result of this collapse and precipitated the inflation.

Banks applied draconian measures on its clients in the absence of an official response to stabilize the Pound. They limited and restricted the transfers outside the country, and imposed limits on clients’ weekly dollar withdrawals. Once the dollars were safely out of the accounts, many would exchange them for Lebanese Pounds.

We entered the money changer’s small cubicle whose blue walls and flickering fluorescent lights triggered my anxiety. The serraf’’s phone rang: “Today, it’s 2,050 Lebanese lira. What will it be tomorrow I don’t know,” he replied, sighting. With a nod of the head, he called my mom and me up to the counter. Buried under wads of money, he pulled out a calculator, a pen, and finally a notebook, angrily flipping through its pages to note down his transactions of the day. Needless to say, he was on edge.

In the tiny elevator on the way out, my mom confessed, “It breaks my heart to do this.”

My mom was in her early twenties when the civil war began.. Her generation had seen the exchange rate fluctuate, and finally stabilize. Did they think they had reached a point of stability? Did they ever expect that thirty years after what was believed to be the end of the civil war they would be miserable again? With a growing number of Lebanese citizens living in poverty basic necessities such as food and diapers became inaccessible.

At 6 PM that same day, the president, Michel Aoun, appointed a new prime minister, Hassan Diab, and charged him with forming a new government. Some believed that by appointing a new prime minister the president was trying to calm down and clear away protesters. But the people remained furious. By this point, they had been on the streets for two months.

I was supposed to head over to the airport with my mother to pick up my brother, who was also coming back for the winter holidays. “Go ahead,” I told her. “I’m going to the protests.” I didn’t know what to expect. I was excited, of course, I had been waiting to get to the streets since that first night of October 17 when I would watch videos of the protests on loop.

A small gathering of around a hundred people met in downtown Beirut, where the protests usually took place, nothing compared to the millions of two months ago, but my first protest nonetheless.

Fatigue was starting to show, as fewer people were on the streets, and you could feel the fragmentation amongst the protesters. Some wanted to give Hassan Diab a chance, while others were not prepared to compromise on their demands: They first wanted the dissolution of the corrupt government and the formation of a new technocratic one. Five people blocked the street in front of the entrance to the parliament building. A few minutes later, another group joined them. Some chanted, others beat on pans, and a few held hastily written banners.

Months of anticipation, of reading and scrolling and wanting so much to be back and on the streets with everyone. But change takes time, and does not happen linearly. So it was that when I finally joined the thawra, everybody else was exhausted.

Saturday December 21

A Saturday night at home in Beirut and one of my brother’s friends was talking about the company he works for, and how they let go many employees. Another friend jumped in to say that salaries were cut at his company to make sure no one got laid off..

Lebanon had almost reached rock bottom, we thought. But something new has emerged: a movement. We now felt responsible for each other. Whoever could lend a hand, spare time volunteering, or provide a meal to those in need, would bend over backwards to help out. A warm but scary feeling.

The fire I had been waiting for so long has finally started. But it had not waited for me.

Lebanon has always been known for its hospitality, its people’s warmth. Foreigners would leave the country talking about how they were offered food and coffee each time they walked into someone’s house, which is undeniably true. But never had Lebanese been so keen on being out on the streets. Not only to fight and protest, but also to help in a makeshift kitchen open and free to all, to receive and distribute donations across the country, and to clean the streets at dawn from the trash protesters left behind at night.

If I were to oversimplify it, the revolution was against the government, the banks, and the corrupt elite. Lebanese needed to hate the same enemy to come together and forget their differences. NGOs and grassroot civil movements flourished from this movement. The regime hasn’t been overthrown yet; poverty and hunger are far from being eradicated. But a spark was ignited, a small fire had been lit.

The fire I had been waiting for so long has finally started. But it had not waited for me.

Sunday December 22

Today was my first time at a real protest. Or so I thought.

As I started exploring the main square where the protesters gathered, I saw the various landmarks that I had seen over the past few months through my social media feeds: the man selling corn from his cart; the wooden fist that was burned down and rebuilt as a sign of resilience; the people banging on metal fences. It almost looked like a tourist attraction.

I felt confused, numb. I was walking aimlessly, with my huge camera flash, like an elephant in a porcelain shop, uncomfortable, trying to find my place in this play where all the roles had already been assigned.

For years I had waited, waited, and waited to see Beirut like this. When everyone else was leaving, I stayed and fought in the hopes of seeing this country stand up for itself. Eventually, I thought I would give the rest of the world a chance. Eventually, I left, too.

But the guilt of leaving followed me to the streets of New York, to my various apartments across Brooklyn, to the houses I called home. Lebanon crawled back to me, through my phone, the news, my dreams and nightmares. I felt that I failed in my mission of making this country better. Then came the thawra and I was left to watch from a great distance all those people and flags, those candles and burning tires, the teargas and tears.

Yet now here I was, back in Lebanon. Or what remained of it. I was finally standing here, where my heart had been for months. But my heart did not feel at home.

The thawra had not waited for me, as I hoped it would. The thawra had a life of its own, a life to which I would have to learn to adapt.

Tuesday December 24

Walking around downtown where the demonstrations took place, I noticed that protesters camping out in tents were worried. A storm was supposed to hit Lebanon that night, and some tents had already been destroyed by the wind.

As I walked towards the tents, I saw a man sunbathing on an office chair outside his tent. “Can I take a picture of you?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said, “go ahead.”

Next thing I knew I was sitting on the fake grass next to him, asking about his opinion on the thawra and what not.

“I don’t have any hope left in it,” said Mohammad, who was 29. “The people are tired. They’re not standing together anymore.”

Akkar has been particularly affected by the economic crisis, with sixty percent of its population living in poverty.

A little boy emerged from the tent behind him, holding a yellow coffee cup. “I still have hope in the thawra!” said the boy whose name was Hammoudi. He and his family were from Akkar, the Northern-most region of Lebanon. Hammoudi used to go to school before the start of the thawra, but since it began he has been camping downtown with his family. Two little girls with matching pink long sleeve shirts and long copper hair arrived, screaming and squealing. They were Hammoudi’s younger sisters, Suzi and Salma. Suzi, the eldest sister, roller bladed her way toward us, while Salma hurried behind with a bag of chips in her hands.

Salma started feeding me chips. “Take some,” she insisted. “They’re really good!” Here I was on a windy Christmas day, sharing chips with this eight year old girl who had been sleeping in a tent for months.

Akkar is about three hours from Beirut, and shares a border with Syria. Along with Tripoli, the capital of the North Governorate—which was also dubbed the bride of the thawra for its peoples’ fury and involvement in the protests—Akkar has been particularly affected by the economic crisis, with sixty percent of its population living in poverty.

“I have faith in the thawra too,” Salma explained. “I’m going to stand for my country, alongside my brothers and sisters.”

Mohammad, Hammoudi, Salma, Sussi and I walked around downtown. Mohammad gave me a tour of the area. “Over here are the tents from this region of Lebanon, and over there, the hotspot of the protests, where everything happened the first two weeks.”

Beirut has always been a city of contradiction, but since the start of the thawra, they grew wider. Tonight, I dressed up in a nice sparkly suit for Christmas Eve dinner with my family. This was the first year my uncle didn’t put up a Christmas tree. Fairy lights and copper Christmas balls didn’t fit the mood. The dinner went smoothly, until the topic of politics and banks came up. Everyone shared their opinion—rather loudly—over turkey, wine, and a yule log.

A Christmas like no other.

Thursday December 26

I joined a protest in front of the Lebanese Central Bank. A rather thin one. Two months ago, hundreds of protesters gathered calling for an investigation of politicians’ bank accounts. Today around fifty people were there.

Before October, the only other other protest comparable was in 2005, after the assasination of then-prime minister Rafik Hariri, when people revolted against the heavy political Syrian presence. For fifteen years some rallies had taken place, but nothing on this scale. I attended a few, hoping they would grow into something bigger, into the thawra. But they all eventually died out.

This time, it was different. In October, some came by foot, others by bus. Some camped and spent the night. Public spaces that were once haunted and deserted now hosted shows and talks. The protests started peacefully, with smiles that accompanied the anger and with chants of rage. Sure, there were burning tires, shattered storefronts, and blasphemies graffitied up on the walls, but aren’t these part of a revolution? Eventually, the government pulled out teargas and water cannons. Protesters answered with rocks.

Today, a flag or two were raised, and some slogans chanted, but the crowd eventually dispersed.

Friday, December 27 and Saturday, December 28

Nightlife has always been important for Beirut. We may not have electricity 24 hours a day, running water, and garbage is scattered on the streets. But we have some of the best clubs in the world.

I went out to three different clubs, all of them packed. Hours stuck in the queues, and the clubs, although full, still welcomed people in. No one could move, let alone dance together. The intoxicating smell of cigarettes, the drinks spilled on the beautiful sequin dresses some girls twirled in, and the loud beat of the bass made this chaotic time in Lebanon feel almost normal. Another weekend in Beirut, the nightlife capital of the Middle East.

Clubbing became a therapy for Lebanon toward the end of the civil war. Today Lebanese went clubbing to escape reality, forget about the banks, and live something of a normal life. But what is normal in this country anymore? Has anything ever been normal?

Economic and sectarian segregation grew wider while the nightlife flourished. The youth kept leaving the country as opportunities grew scarcer, but more night clubs kept mushrooming across the city. International artists would praise Beirut for its diversity and historical richness, while its own population felt uncomfortable with its own history. Was there ever a norm in Lebanon? Or have we grown used to our lack of constant? Will we—or can we—have the strength to build a new constant?

It felt refreshing to be out on the streets that night, natural, the way cities should be.

Maybe Lebanon is more dynamic in the clubs than on the streets.

Tuesday December 31

While some of my friends chose to spend New Year’s Eve in the mountains, I decided to spend it in the city alongside other protesters who celebrated. “All the expats want to go to the streets because you guys just got here,” said a friend who had joined the protests at the outset. “But we have been here for three months fighting, and tonight is the only break we get.”

At 11:50, I was downtown with some friends ready to celebrate the New Year. I had never seen downtown so full of people, life, and lights. There were street performers, food and alcohol stands, and people dancing and laughing all around the square. It was the first time I had seen the square so lively. People demand public spaces. Parks. Places to go on Sunday and spend some family time, without paying an entrance fee.

Less than thirteen percent of Beirut’s urban spaces are open to the public. Where do people spend the nine months when the sun shines bright? Out of 220 kilometers of Mediteranean seaside, only twenty percent remains accessible to the public; the remaining eighty percent are privately owned or inaccessible by foot.

On this 31st of December 2019, I spent my first New Year’s Eve in a public space in Lebanon. Golden confetti was fired at midnight and music blasted. It felt refreshing to be out on the streets that night, natural, the way cities should be. There was nowhere else I wanted to be.

Nowhere in the world, besides Beirut.

____________________________________

From Waiting for Normal by Tamara Saade, text (follow her work on Instagram and Twitter) and Eléonore Hamelin, illustrations (follow her on Instagram and here and on the web). Excerpted with the permission of Delacorte Review. Copyright © 2020 by Tamara Saade and Eléonore Hamelin.

Tamara Saade and Eléonore "Léo" Hamelin

Born and raised in Lebanon, Tamara Saade (text) is a multimedia journalist. Through photography, writing, videography, and social media coverage, she has been focusing on human rights reporting, especially in Lebanon and in the US. She is now based in Beirut, working as a freelance reporter and photographer for national and international outlets. Eléonore "Léo" Hamelin (illustrations) is a documentary filmmaker, journalist and illustrator based in New York. Most of her work tells personal and intimate stories in the voice of her main character—like her last documentary Quiet No More: The Struggle of Reverend Sharon Risher, published in the New Yorker and an official selection at DocNYC. Léo also teaches Video Journalism at the Columbia School of Journalism. She is French and grew up around the world.