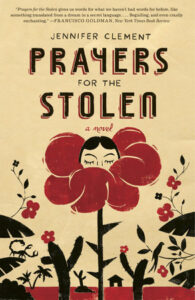

Prayers for the Stolen: How Two Artists Portray the Violence of Human Trafficking in Mexico

Jennifer Clement on Her 2014 Novel and Tatiana Huezo's New Film Adaptation

At the Cannes Film Festival in July, Tatiana Huezo premiered the feature film Prayers for the Stolen, loosely based on my novel of the same name. Also known as Noche de Fuego, Tatiana’s movie—now streaming on Netflix—has garnered many accolades and is Mexico’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Tatiana takes part one of my three-part book and creates a complete world, keeping the story in the rural community and creating a new ending, while my narrative branches off to Acapulco and Santa Martha Acatitla, Mexico City’s women’s prison.

In 2014, after ten years of interviewing women in Mexico, many of whom were the wives and girlfriends of drug traffickers, I published Prayers for the Stolen, which deals with the stealing and trafficking of girls in the state of Guerrero. Guerrero is a prominent area of Mexico for the cultivation of poppies that are processed into heroin for US drug consumption, and where thousands of poor, marginalized, and often indigenous Mexicans are employed. A woman who had left Guerrero to work in Mexico City told me how the women in her community dug holes in the ground where they could hide their daughters while men drove around the countryside looking for girls to steal. It was this information that led to the book: I imagined a rabbit warren of little girls and the act of being buried alive at age six or seven.

While both Tatiana and I have chosen to bring light to the violence inflicted on women and girls in Mexico, we’ve diverged from the popular genre of narco cinema and literature, which tend to be male-driven stories about Mexican drug culture, with graphic violence as a primary part of the aesthetic. This narrative approach has a long history: since the Mexican Revolution at the beginning of the 20th century, violence-as-spectacle was reproduced in photographic postcards and illustrated newspapers; today, it appears in cheap magazines and some tabloids.

It is important to note that documentary film and investigative journalism that delve into these topics have been profoundly important for understanding our time. In fact, Prayers for the Stolen is Tatiana’s first feature film; her most recent and highly acclaimed documentary Tempestad centers on human trafficking in Mexico.

“For me, it was important to build real female characters, full of chiaroscuro.”

In our requiems for Mexico, Tatiana and I have each used artistic elements to describe the most violent events without showing violence. In my case, I wanted to enter this world through metaphor and symbolism. For example, when a character in the book describes a gang rape after she is stolen and returns, she says, “What can I tell you, I was a plastic water bottle everyone took a swig of.”

Similarly, Tatiana also chooses not to depict graphic violence. “Indeed there is a criminal and violent environment, where female characters are exposed to brutality, but I was not interested in victimizing them; that is deeply boring in a movie, and that’s not life,” she says. “For me, it was important to build real female characters, full of chiaroscuro. I think that real contemporary Mexico is harsher than the one reflected in the film. For many years now, our country has been marked by looting, violence, and impunity, and has revealed, among many other things, the collusion between authorities and organized crime.”

My novel is written from the perspective of a young girl, Ladydi, which allowed me to keep the innocence and enchantment of a childlike gaze, and it became a foil against the violence of the environment. When my protagonist sees her friend who has been covered with cigarette burns, she imagines her companion has walked through the Milky Way and that her skin has been turned into a constellation of stars.

Tatiana, whose film is portrayed through the eyes of three young girls, speaks to this also, explaining that she wanted to “…see the world through the eyes of a child—try to understand how that gaze is transformed and eroded when we begin to grow up.” She helps to achieve this effect by placing the hand-held camera at the girls’ eye level—her camerawork the equivalent of my novel’s POV. “Childhood is an ‘island’ where magic resides, and where dark, foreboding echoes of violence lurk,” she says. “Magic begins to evaporate into reality as the border between childhood and adulthood is blurred, and the characters become more exposed and alone. This is a story that invokes the resistance of children and honest gaze in the face of a violent reality.”

In my book and Tatiana Huezo’s film, we’ve both tried through our art to dignify the lives of those whose dignity has been stolen. While neither of us believe our work will change the culture of violence in Mexico, we do believe our approach can awaken, give hope, and build knowledge.

And yet, while girls are trafficked every day, we know art is not enough.

_______________________________________

Jennifer Clement’s Prayers for the Stolen is published by Hogarth Press.

Jennifer Clement

Jennifer Clement is the author of multiple books, including Widow Basquiat and Gun Love. She was awarded the NEA Fellowship for Literature and the Sara Curry Humanitarian Award for Prayers for the Stolen. The President Emerita of PEN International, she currently lives in Mexico City.