Postcards to a Younger, Much Better Novelist

Derek Palacio Shares Early Correspondence with his wife, Claire Vaye Watkins

Not long ago I had a dream that my debut novel, The Mortifications, was reviewed in The New York Times. The review was both good and bad. There was no author mugshot (bad?) but there was a large color photo of the book (good). The review was published somewhere in the middle of the Books Section (not necessarily bad, but not as amazing as gracing the cover), but it was long, spanning, I think, at least three pages (good). I didn’t know who the critic was, though I had a sense in my dream that he was a scholar, because he referenced a number of other books I had never heard of, books that sounded important, beautiful, and (the really bad part) so much better than mine. In fact, the review did not mention my book at all, but only discussed those other books, which, after waking, meant the dream was not a dream, but a nightmare.

As I write this, I haven’t yet told my wife, the writer Claire Vaye Watkins, about this dream, though in the dream itself we read the piece together, repeatedly, as if the only way to make the review better was to keep experiencing it. In the dream she was reassuring and fortifying and encouraging and generally wonderful. In the end, she did manage to make me feel better, such that when I woke from the dream, somewhere around 2:30 in the morning, I didn’t panic, and I thought to myself, That could have been much worse. Which is perhaps why I haven’t mentioned the dream to her yet; it seems she’s already done the work to calm me down. I shouldn’t bother her twice about the same thing.

In his Letters to a Young Poet, Rainer Maria Rilke—before commenting a word on the young man’s work—tells Franz Xaver Kappus, “You are looking outside, and that is what you should most avoid right now. No one can advise or help you—no one.” First things first: we’re all alone.

The first two years of our courtship, Claire and I lived in Columbus, Ohio. She was finishing her MFA work and then writing her first novel while on a generous fellowship from the university. I was just starting my master’s degree. But then, during the spring of 2011, she got her first tenure-track job at a small university in central Pennsylvania. By midsummer, she had packed up and moved, and our relationship was suddenly long-distance. I had one year left of graduate school, and I was doing my best to write a decent thesis, at the time a short story collection. I should mention that she took that job because that university in Pennsylvania was, of all the schools that offered her a position, the closest to Ohio. We could still see each other on weekends just by getting in the car. She did that for me and for us. Still, for a year we were apart, or each of us alone.

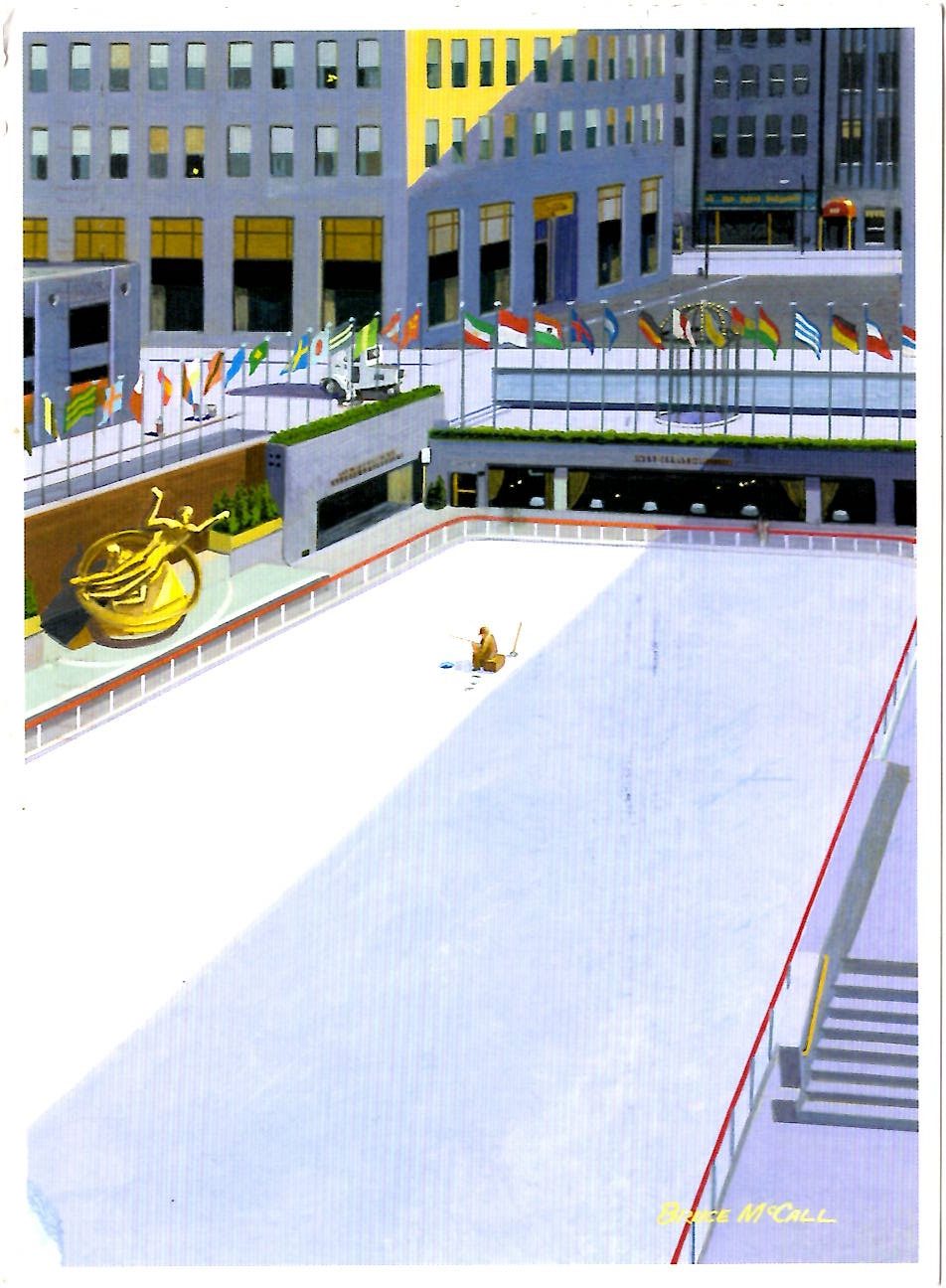

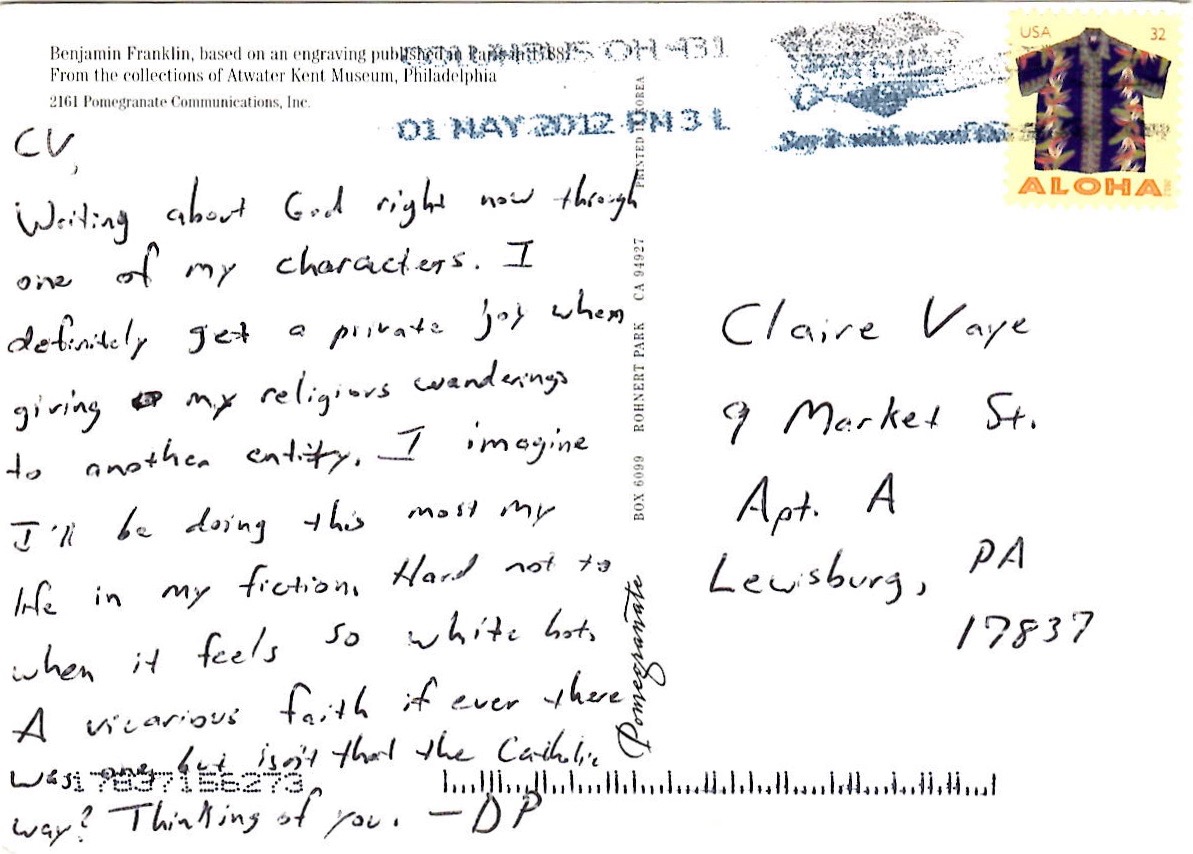

I would have liked to have done something grand to have thanked her for accepting that job. I would have liked to have taken her to Iceland as a surprise, to have bought her a new car, or sent her flowers every day for a year. Instead, I sent her postcards. It was a meager but continuous gift. I tried to send one per day for an entire year, but in the end I only managed 149 total postcards, which is sadly less than half my goal. I don’t think she holds it against me. She has kept every single postcard.

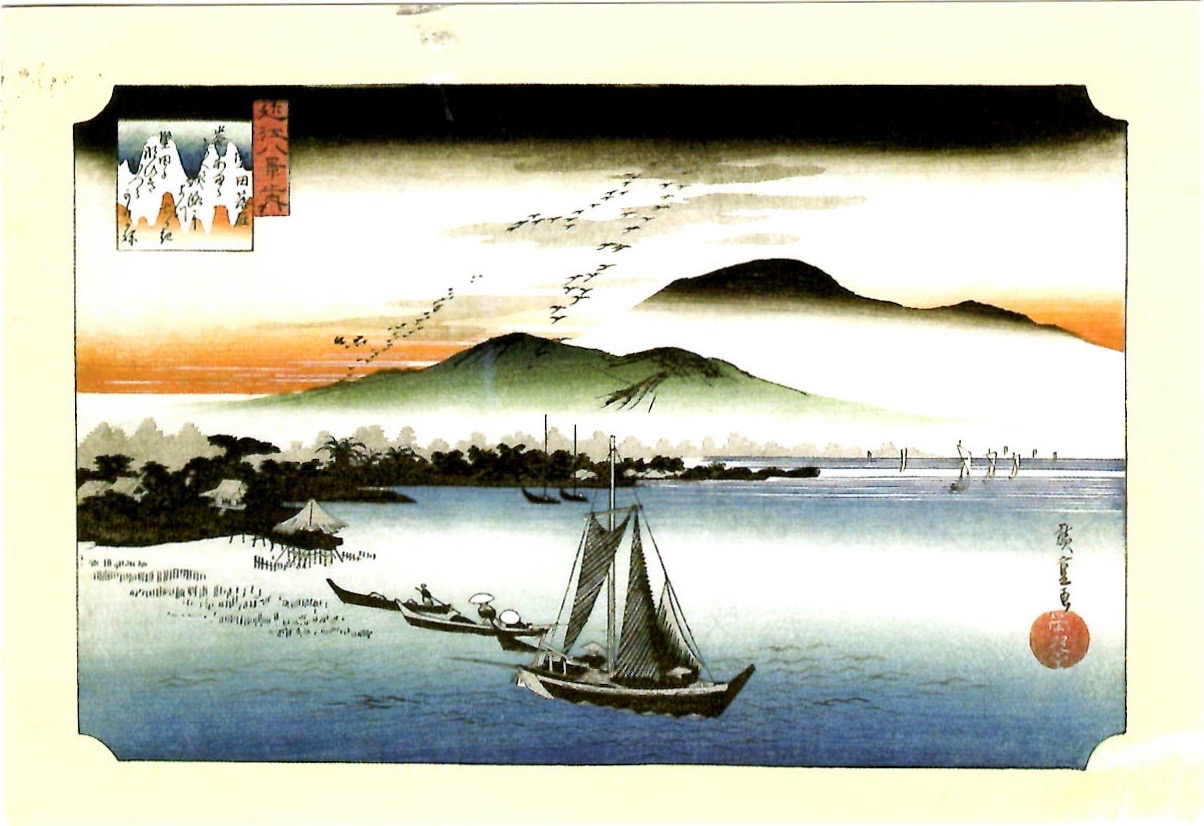

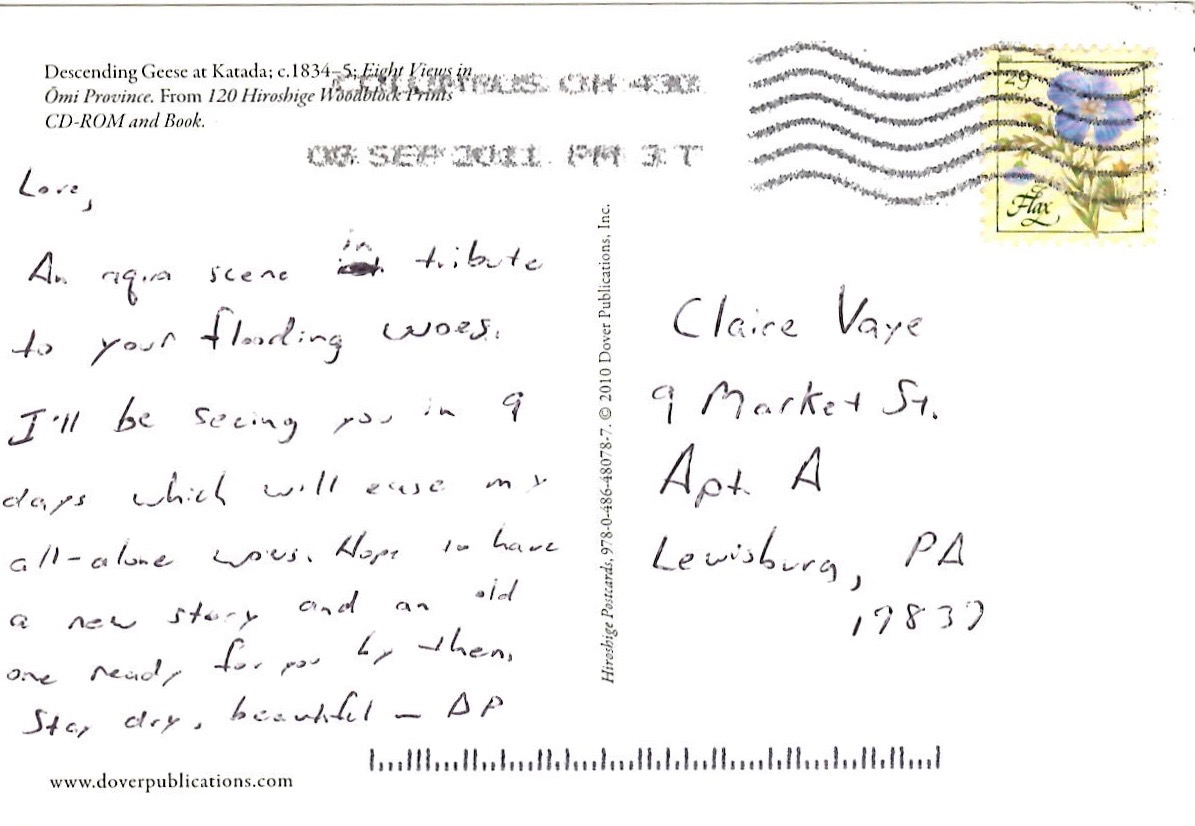

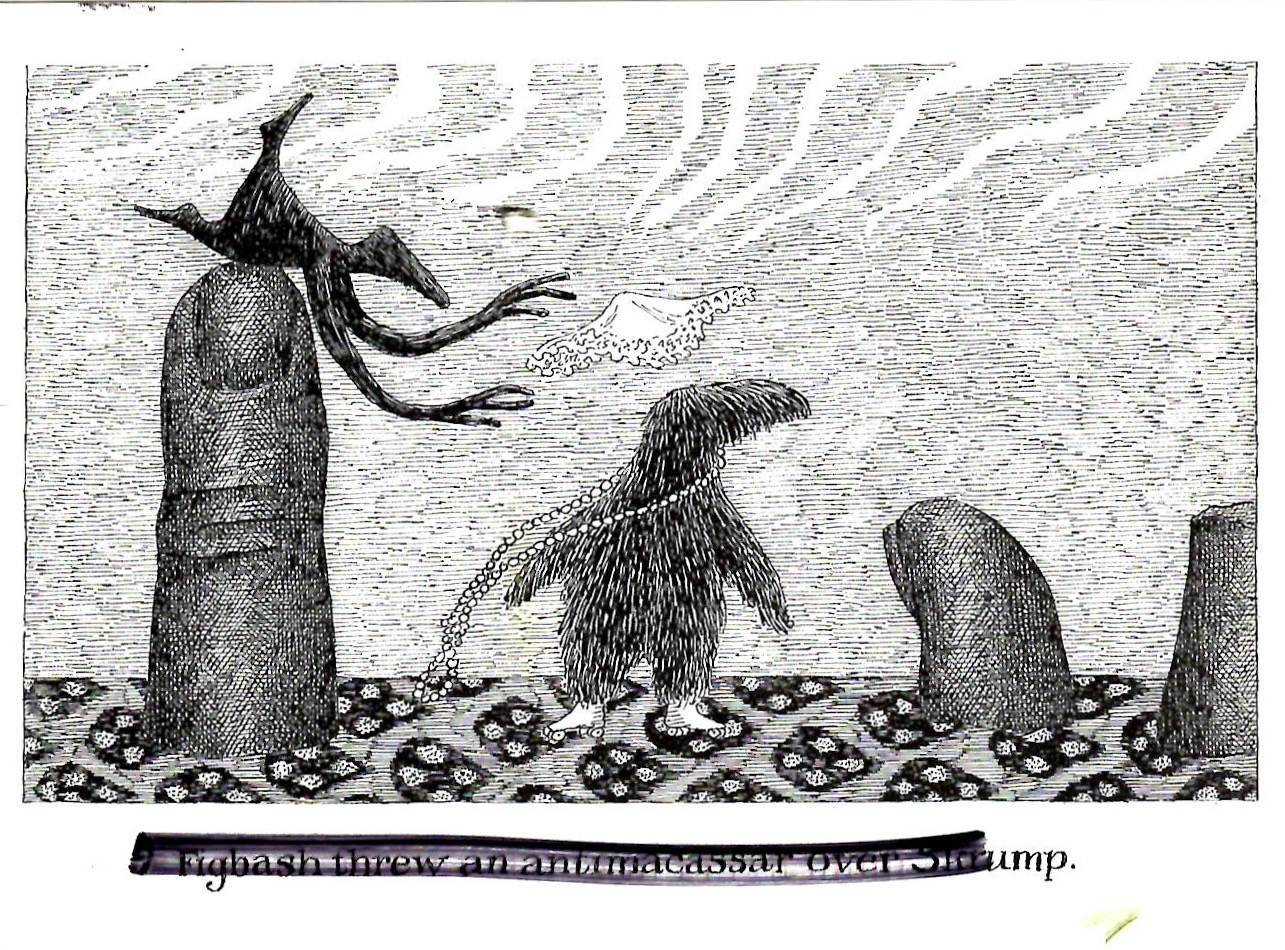

Here is the first, from August 2011, a month or so after Claire left Columbus:

My favorite thing about Rilke’s Letters is that the collection is a one-sided conversation. We never see or read a word from Franz’s catalyzing missives, which I imagine were sincere but also aching in their juvenility. Franz was reaching for Rilke, and grasping upwards requires stretching oneself, arms overhead, torso bared, the soft meat between the ribs exposed. In this early postcard I am reaching for Claire, who, because we often talked over the phone about the contents of my postcards at night, did not write back. It is my landscape analogy that aches. It wants for a natural shaping, for complimentary positions. At the very least it suggests the kind of questions that can become dire over distance: How long will this last? Can we do this? Are we meant to do this? Ordinary questions. Rilke wrote, “Things tremble.”

Something else aches in that first postcard: the beginnings of my novel, which at the time was barely a long story. I can feel even now, even in the brief line about Cuban hills, how fragile the whole thing used to be, how it was, back then, just a possibility. I am casting for plot points that do not yet exist, circling destinations on a blank map. How long will this last? Can I do this?

These things I am talking about are not the same, but they happened at the same time. They grew alongside each other. In my mind and in my memory, I have a hard time pulling them apart. Rilke writes, “…and more unsayable than all other things are works of art, those mysterious existences, whose life endures beside our own small, transitory life.” I cannot un-feel the ways in which writing this novel and our relationship have touched one another.

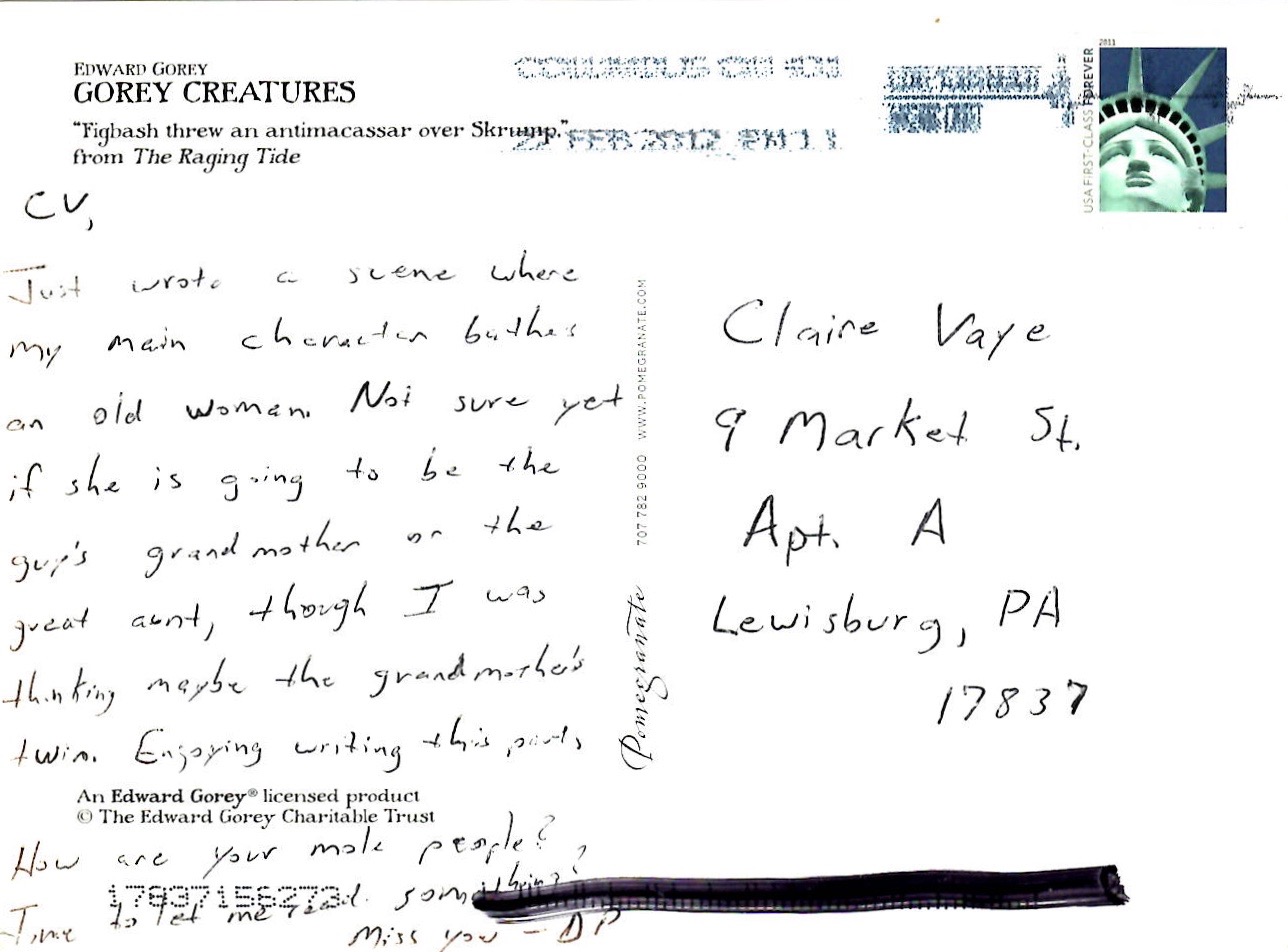

The woman I’m referring to in the Montana postcard is Soledad, the mother character in my novel. The scene I am telling Claire about takes place at the Grand Canyon. Soledad’s lover, Henri, has taken her west to escape, for a time, some of their family troubles back east, namely a daughter who has been accused of murder. While there, Soledad witnesses the owl’s triumph, a moment in the novel that would, eventually, lead to other revelations. It’s a scene in the desert that would become significant. Rilke writes, “There, something of your own is trying to become word and melody.”

Claire and I have visited the American West at least once a year since we got together. Often we go to Nevada, to the Mojave Desert outside of Las Vegas or to the city of Reno. The former is the place of her upbringing, and we go there almost as pilgrims (though she would never say it this way, atheist that she is). We go there to pay respects to the ashes of her parents, which are scattered in a garden outside of her childhood home, which sits just across the Nevada-California border in Tecopa. I grew up Catholic, and despite my poor attendance at weekly Mass, I am still in many ways “of the faith.” I know well the story of Christ’s seclusion, his forty days and forty nights, which means the desert is sacred to both Claire and I. Last year we took our daughter to that desert for the very first time. We showed her the garden, and we introduced her to Claire’s parents. I held her in my arms as Claire stood next me, which meant I was surrounded by this family—parents, daughter, granddaughter—which was also, somehow suddenly, my family. I understood, more so than ever before, that I would spend the rest of my life visiting the Mojave. I realized that from Las Vegas I could drive to Claire’s childhood home—which sits at the end of a dirt road in a town that is not a town but a “census-designated place”—without needing to look at a map.

Everything I wrote in the summer of 2011—what would end up being the first sixty pages of the novel—felt like a detour at the time. The only thing I knew when I started is that the son, Ulises, was going to leave Cuba by the end of the second page, and that by the last page I wanted him returned. I thought, at best, I would need eighty pages in all, maybe a hundred. I thought, at best, it would be a novella. But by the end of August, the manuscript had ballooned. The plot had gotten too complex. I didn’t know what to do with it.

No postcard from September through December mentions the novella/novel-to-be. During that time, I wrote to Claire of other things, other stories. But mostly I counted the days.

Rilke writes, “Everything is gestation and then birthing. To let each impression and embryo of feeling come to completion, entirely in itself, in the dark, in the unsayable, the unconscious, beyond the reach of one’s understanding, and with deep humility and patience to wait for the hour when a new clarity is born…”

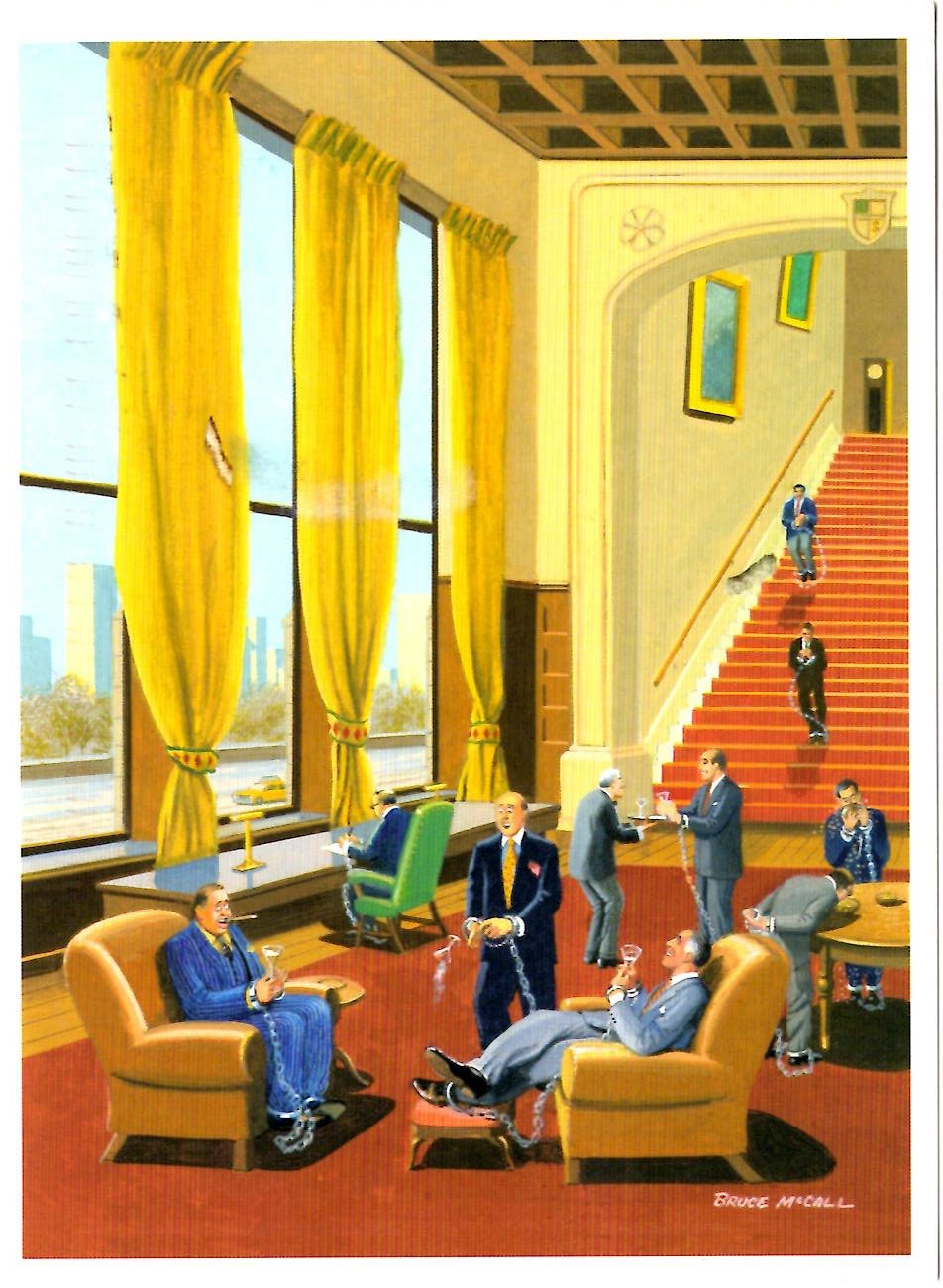

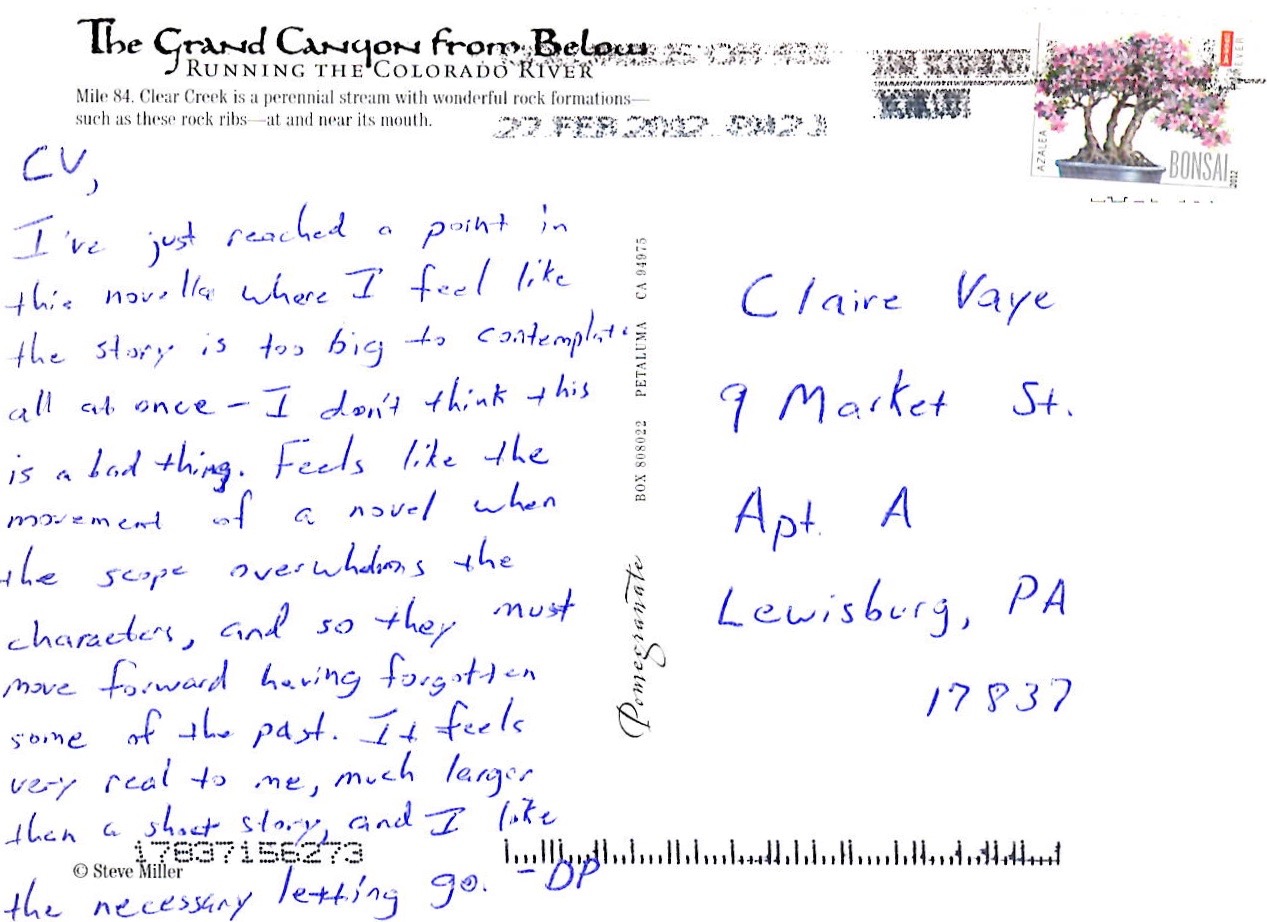

By January of 2012, I had finished every other story for my thesis collection. The only work that remained incomplete was the novella, the same sixty pages from the August before. I didn’t know this at the time, but those sixty pages would, eventually, only amount to a third of the first draft, which meant the thesis, in page numbers, was only half done. For Claire and I, January was also the halfway point in our year apart. We would return to each other in five months. Reentering the novella, I began to write about Ulises’s return to Cuba.

In the novel Ulises meets a young woman, Inez, while passing through Havana in search of his missing sister. As they talk, he discovers that Inez has also left her home, and that she, for her own reasons, also has trouble going back. Once, before we were dating, Claire and I met for drinks at a bar in Columbus. She asked me something—I don’t remember what—but it prompted me to tell her about a young woman I’d started seeing in my last year of college. The woman and I dated after graduation, until we hit some troubles, which led to a year of uncertainty, which only ended when the young woman died one night suddenly in her sleep. When I finished, Claire told me about a young man she had dated while in college. He had problems of his own—drugs and alcohol, a reckless side—and Claire told me how he died one night in a car crash.

In the novel Ulises meets a young woman, Inez, while passing through Havana in search of his missing sister. As they talk, he discovers that Inez has also left her home, and that she, for her own reasons, also has trouble going back. Once, before we were dating, Claire and I met for drinks at a bar in Columbus. She asked me something—I don’t remember what—but it prompted me to tell her about a young woman I’d started seeing in my last year of college. The woman and I dated after graduation, until we hit some troubles, which led to a year of uncertainty, which only ended when the young woman died one night suddenly in her sleep. When I finished, Claire told me about a young man she had dated while in college. He had problems of his own—drugs and alcohol, a reckless side—and Claire told me how he died one night in a car crash.

One of the most difficult scenes to write in the novel—a scene that was hard to tell—was the moment when Ulises is finally reunited with his father Uxbal, a man he blames for much, if not all of the family’s dysfunction. The reunion happens in the hills of the Sierra Maestra where Uxbal is hiding from the government as a failed counterrevolutionary.

In the end, I did check out some Conrad. I reread Heart of Darkness, and I looked to the moment in the book when readers first meet Kurtz. It’s a marvelous scene, full of tension because of the long wait, which is how I felt about Ulises reuniting with Uxbal, a father he’s not seen for years. In my novel I wanted Uxbal to feel as strange and intangible as Kurtz, so I said of him what Conrad said of Kurtz: I wrote that Uxbal’s voice was like “a vapor exhaled from the earth.”

After reading Kappus’s poems, Rilke told the young poet that his “verses have no style of their own.”

But Rilke also told Kappus that “what words point to is so very delicate.” In this postcard I am pointing to my novel via Conrad’s. I am telling Claire that I want my novel to be literature, like Conrad’s. I want to her to read it—the first time I have said so—and I want her to think it literature, which is no small thing.

Delfín is Ulises great-aunt on his father’s side, and in the novel she speaks a dialect of Spanish Ulises can’t fully understand. There is a language barrier, as there was between my grandmother and me: I could not speak Spanish, and she did not speak English. When Ulises finds Delfín living in his childhood home in Buey Arriba, this causes some confusion, and the old woman mistakes him for his father, despite the illogicality of Ulises’s youth. Because they can’t talk, most of their interactions are physical, which is how Ulises ends up bathing Delfín, a moment of intimacy I had not planned for, but discovered in the writing.

For Christmas that year we were apart, Claire and I went to New Mexico to see her family. We rented a house in Taos, near the Rio Grande Gorge and just west of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. On Christmas morning—and despite her nonbelief—Claire offered to attend Mass with me. I did not then and do not now go often to Mass, but I enjoy going to services in new churches. Because the space, the pews, the congregation, the priest and the light are all different, I feel a lovely disconnect. Even though I know the Word and the Nicene Creed and the Our Father, I have to pay a little closer attention. My ear picks up on the nuances of the priest’s foreign cadence, and my eyes wander during Communion, mapping the unfamiliar constellation of Eucharistic ministers. I was even luckier that day because the Mass was told in both Spanish and English, two of the many languages of Taos, and there were parts of the sacrament that I did not, therefore, understand. The estrangement I found beautiful and holy, and for once the ceremony was entirely new, mystical, like something other. I told Claire this afterwards, and she said it had been her favorite Mass as well for the same reason. She disliked any sort of dogma, but the Spanish meant she did not have to listen to it. In this way, we had heard the same things, sat in the same skirt of light pooling from the stained-glass windows. Rilke writes, “We must accept our reality as vastly as we possibly can; everything, even the unprecedented, must be possible within it.”

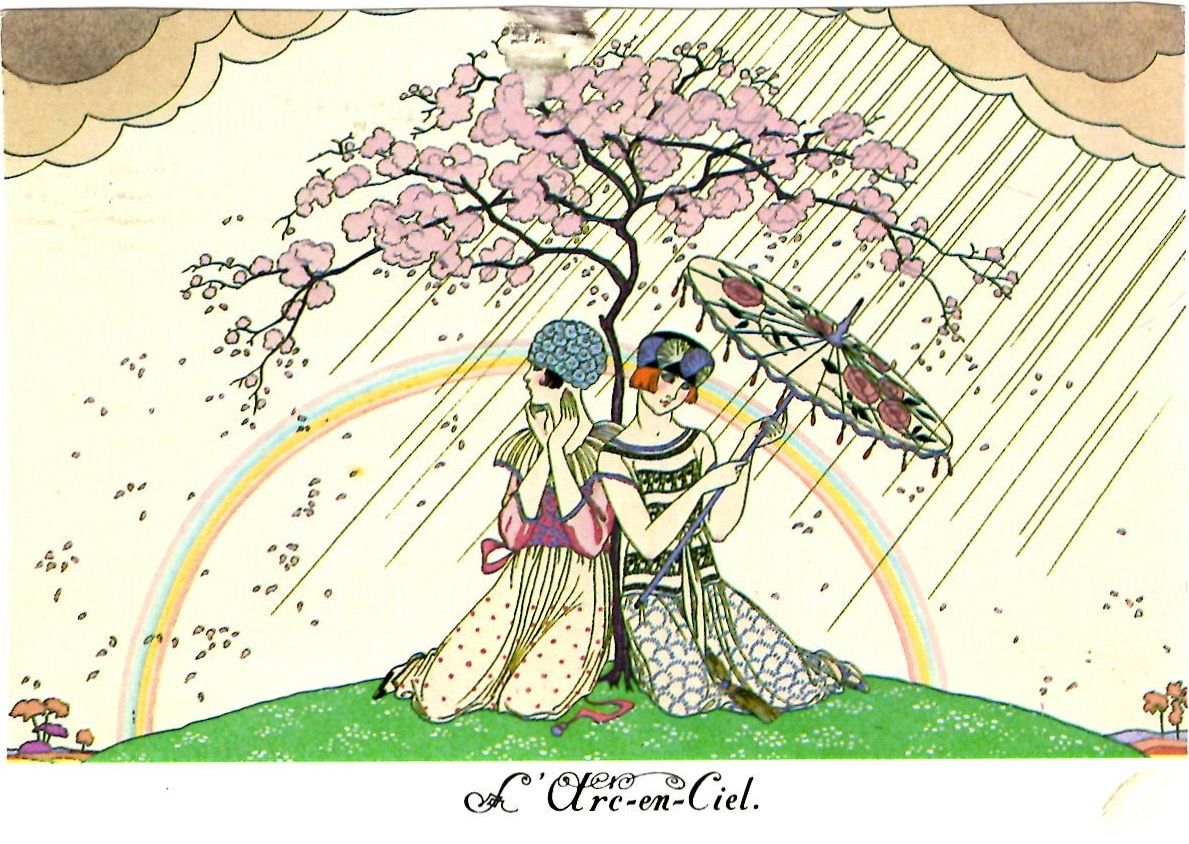

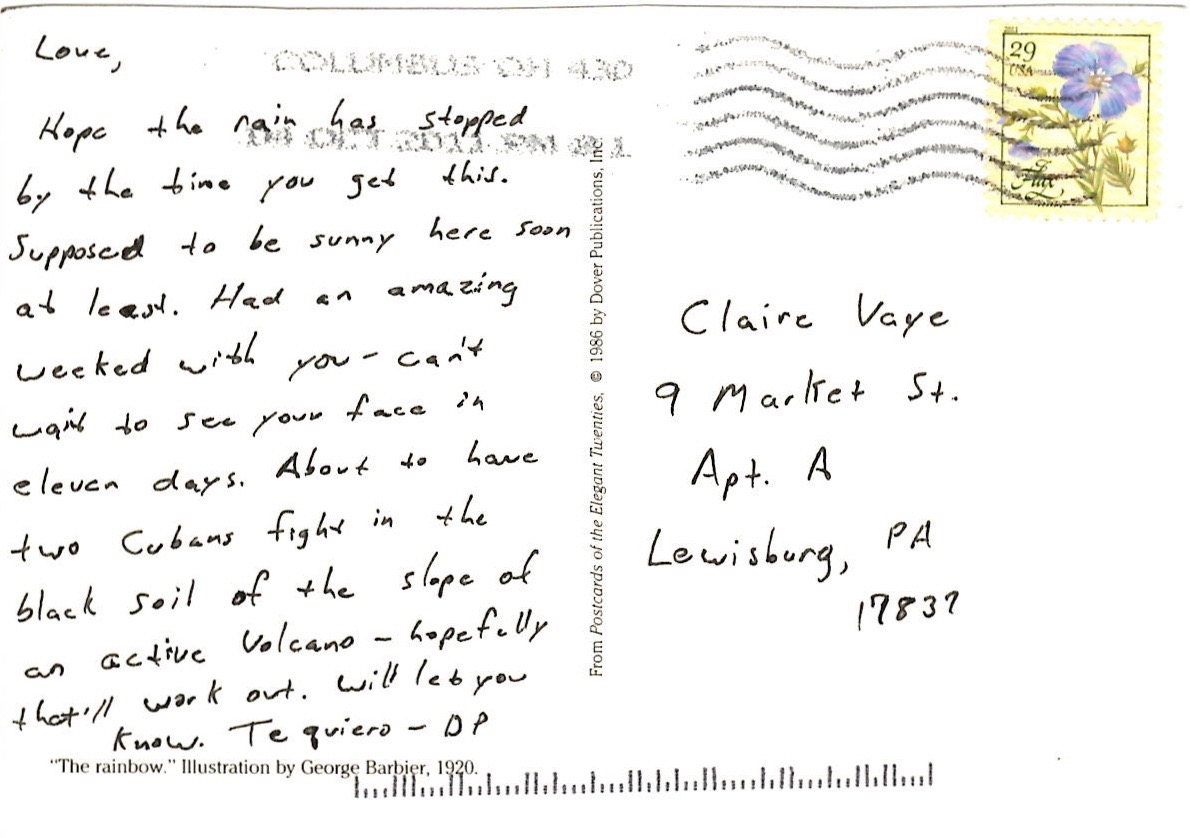

Later, the writing on the postcards begins to swell. There doesn’t seem to be enough space for everything I’m trying to say, especially if those things seem large, unsayable, and beyond the scope of what I had imagined, or thought could happen.

I didn’t accidentally write a novel, but nor did I write the novella thinking it would become a novel. A story I thought would finish one book became its own, though it took me another three years to reach that point. It demanded more of me, a greater commitment (“Every intensification is good, if it is in in your entire blood”). Rilke’s first bit of advice to Kappus is a question: “ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write… if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple ‘I must,’ then build your life in accordance with this necessity.” I imagine this built life might include someone whose presence makes your writing better, both consciously and unconsciously, such that even postcards start to brim with “more of you than you have ever been, even in your best hours…”

I have stolen words from Rilke before. The Mortifications begins with an epigraph from his only novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. It reads, “I have an interior that I never knew of. Everything passes into it now. I don’t know what happens there.” I chose it because I thought it suggested something of my characters’ struggles. It was a nod to the mysterious processes by which they make sense of their lives. It said something about them.

People often ask Claire and I, what’s it like being married to another writer? The question, regardless of tone, always wants to provoke. It suggests two people could not possibly do the same thing without the stirrings of rivalry. I usually laugh at the question, and then tout the benefits of being married to a brilliant author and an exceptional literary critic, a person who will generously read drafts and help me hold my work to the highest standards. A person whose advice I seek and writing I aspire to. A person who can talk me down from unsettling dreams. I also tell others that our love is, of course, not dependent on our work or what we do on the page. We have both of us, at different points, confessed that we might not always write. Yet while that may be true, it is also true that the writing is elemental to our connection. There has never been a relationship without the writing. In all likelihood, there may not be this first novel without our relationship.

Rilke writes, “For one human being to love another human being: that is perhaps the most difficult task that has been entrusted to us, the ultimate task, the final test and proof, the work for which all other work is preparation.”

Derek Palacio

Derek Palacio received his MFA in Creative Writing from the Ohio State University. His short story “Sugarcane” appeared in The O. Henry Prize Stories 2013, and his novella How to Shake the Other Man was published by Nouvella Books. He lives and teaches in Ann Arbor, MI, is the co-director, with Claire Vaye Watkins, of the Mojave School, and serves as a faculty member of the Institute of American Indian Arts MFA program. His novel The Mortifications is out now.