Porochista Khakpour on Learning to Own the Discomfort of the Body

"To Find a Home in My Body is to Tell a Story That Doesn’t Exist"

I have never been comfortable in my own body. Rather, I’ve felt my whole life that I was born in the wrong body. A slight woman, femme in appearance, olive skin that has varied from dark to light, thick black curly hair, large eyes, hands and feet too big, of somewhat more than average height and somewhat less than average weight—I’ve tried my whole life to understand what it is that seems off to me. It’s deeper than gender and sexuality, more complicated than just surface appearances. Sometimes the dysmorphia I experience in my body feels purely psychological and other times it feels like something weirder. As a child, I thought of myself as a ghost, an essence at best who’d entered some incorrect form. As I grew older, I accepted it as “otherness,” a feature of Americanness even. But every room I walk into I still quickly assign myself to outsider status, though it seems not everyone can see this. Many have in fact called my looks conventional, normal, even “good.” I’ve accepted it while also feeling like I’ve deceived them.

I’ve looked for answers from my first few years on this earth, early PTSD upon PTSD, marked by revolution and then war and then refugee years, a person without a home. Could that have caused it? Was displacement of the body literally causing a feeling of displacement in the body?

Only decades later did I confront something that may have been there the whole time: illness, or some failure of the physical body due to something outside of me, that I did not create, that my parents did not create. Illness taught me that something was wrong, more wrong than being born or living in the wrong place. My body never felt at ease; it was perhaps battling something before I knew it was. It was trying to get me out of something I could not imagine.

At some point, with chronic illness and disability, I grew to feel at home. My body was wrong, and through data, we could prove that.

Because my illness at this stage has no cure, I can forever own this discomfort of the body. I can always say this was all a mistake. To find a home in my body is to tell a story that doesn’t exist. I am a foreigner, but in ways that go much deeper than I thought, under the epidermis and into the blood cells. I have started to consider that I will never be at home, perhaps not even in death.

*

The one thing I do know: I have been sick my whole life. I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t in some sort of physical pain or mental pain, but usually both.

“My body never felt at ease; it was perhaps battling something before I knew it was. It was trying to get me out of something I could not imagine.”

I was born in Tehran in 1978, infant of the Islamic Revolution and toddler of the Iran-Iraq War. Like many Iranians of their educated, progressive, Western-friendly upper class, my parents did not last there. My first memories are of pure anxiety, buses and trains and planes with my two parents, who I was cognizant were just two clueless beings—a 26-year-old, a 33-year-old, both often in a panic, occasionally in tears. Furiously I told stories to distract them, books the only toys we could fit into our two suitcases. Whenever I could, I took pen to paper and drew images and had my father dictate my narrative. It was not much, but it was something; storytelling from my early childhood was a way to survive things. Meanwhile I tried to ignore everything in the air—hot air balloons, helicopters, later fireworks and light displays—that resembled air raids and bomb sirens. I knew to hide my trauma, at least until we found a home.

This isn’t your home, my father would say when we got to the US. We’ll be going home again one day soon.

He said that for three decades. Now in the fourth, he likely still says it.

Years later several doctors, and also my own parents after they’d read some study, told me that if a child is exposed to significant trauma in the first three years of their life, they could have significant psychological repercussions later in life. PTSD. The brain of a child develops at high speeds, those first few years a time of rapid development. And as their brain develops, so do their emotions.

No one who knows this study has ever let me forget this fact.

Like most Iranians we ended up in Tehrangeles—almost. The portmanteau referred to the enclave in the West Side of Los Angeles that had become home to an Iranian diaspora, mostly refugees on political asylum like us, but also many other wealthy Iranians who simply felt at home in the Southern California of luxury and hedonism, far before a siege on their homeland would force them out. But while we’d spend weekends there at various kebab houses, driving around Rodeo Drive and gaping at rich Iranians flaunting their nose jobs and carrying designer shopping bags, and going on long rides to see their McMansions, we never lived there. We were 45 minutes southeast, inland in the East Side suburbs, from Alhambra and Monty Park to eventually South Pasadena. My parents were no longer crying at least.

__________________________________

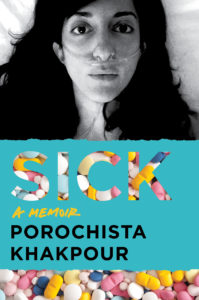

From Sick. Used with permission of Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2018 by Porochista Khakpour.

Porochista Khakpour

Porochista Khakpour is an Iranian American novelist, essayist, and journalist. She is the critically acclaimed author of Sons and Other Flammable Objects, The Last Illusion, Sick: A Memoir, and most recently, Brown Album: Essays on Exile and Identity.