1

He went out in the morning to look at a painting. It was early, so he had set his alarm, but he didn’t even need it—ten minutes before it was supposed to ring, his eyes came open, both at once. Was that usually the way? Did some people open one eye and then, after a while, the other? How many people woke but kept their eyes closed, trying to stay inside the cylinder of sleep? These were all good questions, but he needed to be out of the house to see the painting.

2

Most days he collected the newspaper and began his day by reading it in the chair beside his bed. This was a holdover from the days when he had been married, and when something about the presence of his wife in the bed—her beauty, mainly, which was far greater as she slept than when she was awake—had stung him. He had needed to be out of that bed, on his feet, brushing teeth, checking his reflection in the mirror, performing various ablutions and eliminations, and finally going for the paper, which allowed him to settle into the activities of the broader world. Only then could he return to his wife and wake her, an act that shifted her face from the supreme beauty of its sleeping state into the more complex, not entirely lovely aspect it possessed when awake. She knew he was disappointed seeing her awake. It must have been obvious from his expression. In the face of that knowledge he burrowed into the newspaper even more aggressively. His wife had laughed harshly at his attempts to escape. “Are you trying to read under the words?” she had said, and then said that she was going to order a needlepoint sampler with that question on it. That was her ironic way of dismissing one of her own questions or remarks, though, in fact, it was a strategy for suggesting that the question or remark had been particularly profound. She devoutly believed that many of the things she said deserved to be framed and hung on the wall.

3

In the past the newspaper was central to his morning ritual. But there was no more wife whose sleeping face was too beautiful for him to look upon—she had left him and moved far away—and at any rate today was a special day. Today was the day he was going to see the painting. For a moment he was not sure how he would adjust his ritual without destroying it, but then inspiration struck. He knew what he would do. He would bring the newspaper in from the front lawn, but he would not read it.

4

He stood outside checking the sky. Light was beginning to come into it, and when he saw that it was clear—not quite blue yet but the color of a bruise healing—he decided to walk into town. As he went back inside, he bent to collect the paper and saw the top headline, something about the murder of a young man down at the waterfront. He wished he hadn’t looked. The young man had the same name as a man he had once known, though it could not have been the same man. The man he had known was older than him, and was long dead. That man had been a professor of his in college. He had introduced him to another man, a lawyer who had given him his first job, and that lawyer had in turn introduced him to the man who had gotten him interested in art. This third man was the uncle of the woman who had become his wife. He thought of this third man as his mentor. This was many years ago, in another city.

5

The other city had a world-renowned museum. He had visited it only twice, once with the man who had been introduced to him by the man—his mentor—who had been introduced to him by the professor, and once on his own. The second visit was the one that had truly hooked him. He had stood in front of a canvas that was bright orange at the top and dark brown at the bottom and all gradations going downward. He had imagined that the orange was life and that the brown was death, and that the canvas was a kind of clock that showed the passage of time. He tried to locate himself on the canvas. Back then, he had been nearer to the orange.

6

He dressed, remembering the woman who had been with him a few evenings before. She was a lawyer from the office down the hall from his own law office. “We have lots in common,” she said, though this was not in fact the case. She specialized in taxes. His rm specialized in rules governing the sale and purchase of commodities. She was short and brunette. He was tall and had been blond when his hair was present, though now it was mostly gone, down to a hint at each temple. She was a woman. He was a man. Maybe that was what she meant. He had taken her to dinner twice at the same excellent seafood place (portions the proper size, price expensive but not too expensive), and the third time she had nodded as he asked but then said she was in the mood to eat something else, and that she would be over at his place after work. It had taken him longer than it should have to see how forward she was being. It had taken him until he nodded, told her he would see her around seven, walked back to his desk, and started reviewing a case that revolved around the question of interstate commerce. Then it hit him and he blushed crimson.

7

She had been at his house at seven. She had been undressed by seven-ten, had him in the same vulnerable state by seven-fifteen, and had put him through his paces until nine o’clock, at which point they had ordered pizza and eaten it while they watched a true-crime television show. The episode they watched also concerned the waterfront. “I don’t like it when people talk about violence,” she said. He had agreed but she had stopped him. “I don’t know if you know what I mean,” she said.

“I mean that I don’t like it because I think that violence can be a great and positive thing if used correctly. A show of force, even rough, even cruel, can be compelling.” She was being forward again. Suddenly it was eleven o’clock, post-paces again. They slept perpendicular to each other.

8

The morning he woke up with the woman he noticed her beauty while sleeping paled to her beauty while awake. It was her eyes that were lively and sharp. He woke her quickly. She made use of him one more time before work. That morning his ablutions and eliminations were automatic to the point of belonging not to him exactly but to the boilerplate of the universe. Now, days later, he remembered them. He even remembered his wife. That meant the presence of the woman was beginning to fade.

9

Valuable time was being chewed up by the jaws of idle thought. Would this sentence have made a good needlepoint sampler? He hardly had time to think about it. He hurried on the rest of his clothes and made for the door. He had to walk fast if he was going to make it. He had seen the painting before, but not in person, which meant he had not seen it at all. That was one thing that his mentor had told him many years ago. A painting was not simply an image. A painting was a thing. When it was reproduced in a newspaper or magazine, it received a push toward death—a small push, a weak push, but still a push. It was fixed by the impersonal eye of the camera, and as such was memorialized. When a painting was viewed in person, it exploded outward from its square on the wall, in color, in texture, in size, even in smell (though, the man said, the smell of a painting operated on a viewer at a not entirely conscious level). In person a painting grabbed you by the lapels. In a newspaper or a magazine, it meekly offered you its lapels to grab.

10

He had seen this painting in the newspaper the previous day—that newspaper he had collected in the early morning hours and brought back to the kitchen table where his female visitor was already sitting. She had read the front section while he had taken the rest. She had clucked her tongue at the events of the world and he had solaced himself with sports scores, the prices of stocks, the funny pages, and finally with various beautiful pictures: of dancers, of new buildings in the downtown, and finally of the painting. It was a painting of a large face, and in each eye of the face there was a large reflection of a large building, and each window of the building was itself a kind of painting. All manner of things were happening in those windows.

11

The article in the newspaper had not just shown the painting. It had discussed it at some length. His mentor, who had not been thrilled about the way newspapers and magazines showed paintings, had been more sanguine about the way newspapers and magazines discussed them. “The medium is language,” his mentor had said, and stopped, and shook his head, as if coming free from a deep sleep. After a few long seconds, he had resumed speaking. “The medium is language even when language is not the medium.” He went on to explain what he meant: that man was capable of many different acts of construction or arrangement or organization, as were other animals, but that what made them creative acts, in the commonly understood sense, is that they could be ascribed meaning through language. His mentor’s disquisition lasted for nearly five solid minutes but what remained behind was mainly that initial aphorism, a perfect sampler.

12

The discussion of the painting in the newspaper had gone on at length as well, and had one point that shone brighter than the rest: in this case, it was the insight that the painting was best viewed early in the morning. It was being exhibited in the lobby of an office building a few blocks away from his own office. It had been commissioned for that space. But, as the article said, while it improved and energized that space at all times of the day, it pulsed with its truest energy in the hour after dawn. It was something about the colors and the composition, something about the size and the shape. It was something about everything about the painting. “It can be seen, and appreciated, at any hour,” the article said, “but if seen during the first hours of the day, it may save your life.”

13

He walked to town, wondering when next a woman would come to his house, and whether it would be the same woman from last time, and if so, if the same things would happen, and if not, what other things would happen. As he went, he tried to remember the image of the painting from the newspaper, and in particular what he thought he had seen in the windows in the building in the painting, or rather what he had imagined he had seen there, which was the same as what he believed happened in the city over the course of any several days: several births and several deaths, several acts of love and several acts of violence, a few moments of spectacularly byzantine perversion that resulted in peak experiences of passion for all involved (one character he imagined was brought to such a state of carnal excitation that she found herself temporarily unable to recall any of the seven continents, and panicked until one began to take shape in her mind, the big one in the middle, where all life had begun, she almost had the name, it was a song, Africa), a few murders, a man alone, a man back from a walk.

14

He came into town about twenty minutes past dawn and went straight to the building where the painting was being exhibited. It was being exhibited in the lobby. The lobby was locked. He knocked on the glass door. A man in a uniform was sitting in a chair reading the newspaper, his feet up on the desk beside a bank of monitors that showed empty rooms and hallways. The man in the uniform stood, walked to within three feet of the door, stopped, and pointed at a framed sign on the wall outside the glass that displayed the building’s hours of business. Then he went back to his chair and his newspaper.

15

He kept knocking but now the man in the uniform did not answer. He pressed his face to the glass and squinted at the painting. He could not quite see it. He saw the outlines of the face but none of its features. The eventful windows in the building in the painting, so wonderfully rendered even in the picture in the paper, were at a difficult angle, and weakened to dull gray rectangles. He waited for a brainstorm that would help him salvage the day but no inspiration came to him. He was marooned in the sad facts of the morning, which was that he had gone out to look at a painting. It was early, so he had set his alarm, but he hadn’t even needed it. And now he was not able to see that painting. He was suddenly exhausted. He was closer to the brown. He did not love the woman who had come to his home, though she had put him through his paces. He still loved the woman who had been his wife, though she had been more beautiful asleep than awake and had left him at any rate. He closed his eyes. Did some people close one eye and then, after a while, the other? How many people closed their eyes and imagined they were no longer in the world? These were all painful questions, and he stood in the space outside the glass and waited for time to pass and the building to open so he could have a lesser look at the painting he had been led to believe might save his life.

__________________________________

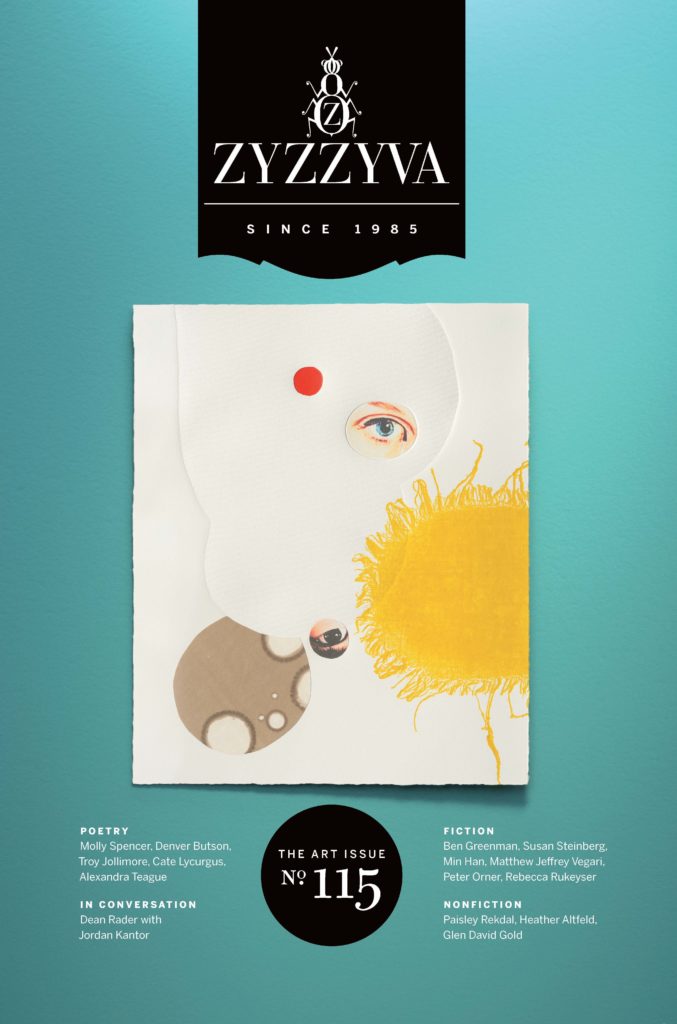

First appeared in ZYZZYVA No. 115 Spring 2019. Used with permission of ZYZZYVA. Copyright © 2019 by Ben Greenman.