How a Single Violent Crime Tells the Story of U.S.-Japan Relations in Okinawa

On the Long Shadow of American Empire

On the evening of April 28th, 2016, Rina Shimabukuro put on her red sneakers and black parka to go out for a walk. Twenty years old, Rina was an office worker with long, dark hair and girlish bangs. She stood about five feet tall, and when she smiled, she showed off a set of straight teeth. One childhood classmate characterized her as friendly and good-natured, a girl who had been quiet in the classroom but broke out her singing and dancing skills when hanging out with friends.

Around 8 pm, Rina texted her boyfriend that she was going walking and left the apartment they shared in Uruma City, on Okinawa’s central east coast. A river ran through the area where she walked. One side was both commercial and residential, filled with apartment buildings, restaurants, fishing shops, a Don Quixote mega-store crammed with discount household goods. The other side was more industrial, with warehouses and smokestacks, recycling centers and shipping companies. The roads were wide and cut by medians, where trash got caught in the weeds. A new-looking paved path ran alongside the overgrown river. A sign there warned walkers to pick up after their dogs, and a small pavilion offered a place to sit in the shade. The ground was littered with cigarette butts and bottle caps, and stray cats hissed from the underbrush.

A few hours after Rina went out, her messaging app showed she had read a text from her boyfriend. She didn’t respond. She didn’t come home. She didn’t have her wallet. The next morning, her boyfriend reported her missing.

Over the next few weeks, Rina’s friends posted about her disappearance on social media, and people speculated about what had happened. Some thought she had been abducted by a religious cult. Others suspected the boyfriend, who was Okinawan too. Meanwhile, the police worked the case. They circulated a missing-person flyer. They used GPS data to track her cell phone to its last location, the industrial zone near the river. They surveyed security footage of the area, combing through the hundreds of cars caught on camera. The breakthrough came when they brought in the owner of a red SUV for questioning.

Kenneth Franklin Gadson was 32, an African American ex-marine who had been stationed on the island for a few years. The marine corps had sent him back to the United States in 2011, and after his honorable discharge he returned to Okinawa in 2014. He found a job on Kadena Air Base, working as a civilian contractor at a company that provided internet and cable TV to the U.S. bases. He married a local woman (who was “kind and very good looking,” according to a neighbor) and adopted her last name, Shinzato. They had a baby and moved in with her parents a half hour’s drive south of Uruma, in a small seaside town. “It looked like he was living a normal life,” another neighbor said. But under police questioning, Gadson confessed that he had spotted a girl walking, pulled over, and assaulted her. He led them to her body in the woods.

*

When I traveled to Okinawa the next year, people were still talking about the murder. Gadson had confessed, but the grisly details of that night were still emerging, and his trial loomed. In the absence of facts and closure, rumors spread. Rina Shimabukuro and Kenneth Gadson were secretly dating, some locals told me; it wasn’t a random crime. She was pregnant with his child. She was pregnant with his child, and his wife had found out, and his wife was the one who killed her. Gadson had just disposed of the body, then taken the hit for his wife. The people who told me these stories tended to support the U.S. military presence on their island. Some seemed confident in their version (everyone in Uruma City knows the truth). Others were more uncertain (that’s just what I heard) or indignant at the local media for distorting the truth (fake news). Anti-base activists, on the other hand, blamed the U.S. military for starting any rumors about a romance (propaganda).

I believed the news and didn’t think the rumors were true, but I wanted to know why Rina’s relationship to her killer mattered so much to so many people. So what if she had been dating the man? He killed her and dumped her body in the woods. Her dating him didn’t lessen that crime. But to many people, it did.

NO RAPE NO BASE read the sticker at her memorial. NO RAPE NO BASE read the signs at many anti-base demonstrations. NO RAPE NO BASE read the sticker that appeared on an electric pole near the Uruma City home of an Okinawan woman I knew. Arisa was married to an American ex-serviceman who worked on base, and they had two young kids. “What does rape mean?” her eight-year-old son asked when he saw the sticker. Arisa was horrified, feeling like someone had put it there for her family, making some nauseating commentary about her husband. She avoided her son’s question, but he kept asking. Her husband tried to scrape off the sticker, but someone put up another one.

I became interested in Rina’s story because it, like too many others before hers, came to mean much more than the crime itself. It came to mean something about the U.S.–Japan security alliance. In Okinawa, where there’s a long-simmering tension over the U.S. military presence, stories about locals and Americans become allegories, and there’s a war of stories going on. The pro-base side circulates videos of belligerent demonstrators outside the base gates to show the protest movement is driven by discrimination and hate. A video of marines cleaning up a local beach or visiting an Okinawan senior citizens’ home means the U.S. military presence is altruistic.

“If you get the community relations right, the politics fall in place,” Robert Eldridge, a former military public affairs official, said in the wake of Rina’s death. Eldridge called for more publicity of servicemen in Okinawa doing “good things.” What he didn’t say was that he also believed in publicity of Okinawan activists doing “bad things;” Eldridge reportedly had been fired from his position with the marines for leaking a tape of a prominent activist illegally stepping on base before being arrested. The tape ended up in the hands of Japanese neo-nationalists, the far right.

For anti-base activists, the most powerful story is a rape. A rape of an Okinawan woman or girl by a U.S. serviceman snaps people awake in ways a helicopter crash, chemical spill, bar-room brawl, or threatened coral reef can’t. A rape captures the imagination of the public and media because it’s a story in our bones—a metaphor we understand right away, without explanation. We’re used to anthropomorphizing geography in this sexualized, feminized way. We talk about virgin land, Mother Earth, the rape of Nanking. When a U.S. serviceman rapes a woman in Okinawa, Okinawa becomes the innocent girl—kidnapped, beaten, held down, and violated by a thug United States. Tokyo is the pimp who enabled the abuse, having let the thug in. Soon, no one is talking about the real victim or what happened; they’re using the rape as the special anti-base weapon that it is.

In Okinawa, where there’s a long-simmering tension over the U.S. military presence, stories about locals and Americans become allegories, and there’s a war of stories going on.A rape has the power to assemble world leaders, spark mass protests, and shape global affairs. In 1995, the gang rape of a 12-year-old Okinawan girl brought out more than 90 thousand people in protest. The swelling of public anger was so great that leaders agreed to close Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, dubbed “the most dangerous base in the world” because the homes, schools, and shops of Okinawa’s Ginowan City push against its fences, in the path of the aircraft that take off and land there, day and night. The catch was that in return for Futenma’s closure the U.S. military would build a new, bigger base on Oura Bay in the island’s north. In 2017, when I returned to Okinawa, protest over this new base was raging, and activists were in need of new ammunition. Maybe what happened to Rina Shimabukuro could make a difference. It all depended on the details of her story.

Because the 1995 rape was so brutal, the victim so young (and a schoolgirl, the epitome of innocence and titillation in the Japanese imagination), that incident made the biggest political impact. Even a murder didn’t trump it; there aren’t any NO MURDER NO BASE stickers. For instance, a few months before the 1995 rape, a U.S. serviceman on Okinawa beat his Japanese girlfriend to death with a hammer. “He hit her head more than twenty times or something,” veteran journalist Chiyomi Sumida told me. “It was such a vicious murder.” But she said hardly any reporters attended the trial. The woman’s death didn’t mobilize tens of thousands of people. The woman’s death isn’t in Okinawa history books and museums. The woman was dating the soldier, and she was from mainland Japan. She wasn’t a good symbol.

Sumida explained the general attitude toward cases like that: “If you don’t want to get involved with trouble, then stay away from” U.S. soldiers. If you date an American and something terrible befalls you, “you asked for it.” She said the media plays into this victim-blaming. “There’s always a big, clear line,” Sumida said. “If you are dating the person, and you get raped or injured, you don’t get much sympathy from the public.” That was why she thought people—she didn’t know who—started “groundless rumors” online about Rina Shimabukuro dating Kenneth Gadson. If Rina was raped before she was murdered, people suggested—if she really was just walking down the street (but why was she out alone after dark?) and was randomly nabbed and assaulted—the incident was proof that the bases should close. But if she was having sex with the guy by choice, if she chose to interact with him, and he ended up killing her, her story wasn’t a condemnation of the bases. It couldn’t be used as a metaphor to represent the entire situation.

I started gathering my own stories of people in Okinawa because I was tired of hearing these crude dichotomies, wielded for political use. The pure, innocent victim and the slut who asked for it. The faultless activist and the rabid protester. The demonic American soldier and his savior counterpart. They’re all caricatures, and if we’re using them to understand the larger political, sociohistorical situation—the U.S. military in Okinawa, and by extension the U.S.–Japan security alliance and America’s system of overseas basing—we’re not getting anywhere. Dichotomies like these disempower and silence the real people involved with the bases, the full cast of characters who often inhabit ambiguous spaces.

As an allegory, a story like Rina’s is incomplete. Her death is tragic and disturbing and representative of the widespread U.S. military violence against local women that stretches back to the American invasion. It taps into deep emotions concerning Japan and the United States that many Okinawans feel. But as a metaphor for the entire story of Okinawa and the U.S. military, it leaves out much of the vast, complicated reality.

What I found, as I traveled the island, is that most locals don’t have a simple victim relationship with the U.S. military. Instead, since the end of World War II, Okinawan people have been actively engaging with the U.S. military empire, whether helping to enable or disable it. Local men and women—more often women, because of the predominantly male nature of the military—seek out relationships with the bases and their inhabitants, relationships that are often symbiotic, even if they’re problematic. Many locals’ motives center on love or money, but Okinawans also find community and new identities in the base world.

As for the bases, connections with local people help the military installations run smoothly, boost the emotional health and built-up masculinity of soldiers, and make the bases harder to close. The bases may have arrived by force, but they have stayed because of the complex relationships formed with people living outside the fences. The truth is that when Okinawans choose not to cooperate, when they decide to challenge the U.S. military presence, their actions have the power to rattle the whole system.

During my stays in Okinawa, I spent time with locals, mainly women who live around the bases, in the contact zone. These are women who date and marry U.S. soldiers, who work on and around the bases, who have fathers or husbands in the military, who fight against the military. Even if not as obviously as the 1995 rape victim or Rina, these everyday women are players in the larger geopolitical game, influencing, challenging, and smoothing the way for the U.S.–Japan security alliance. Their stories reveal how deeply American bases abroad affect local communities, importing American ideas of race, transforming off-base cultures, shaping people’s identities. Unlike the popular victim narratives, their stories paint a nuanced portrait of the U.S. military presence in Okinawa—how it persists, how it should change, and what life is like at the edges of the American empire, in all its darkness and glory.

__________________________________

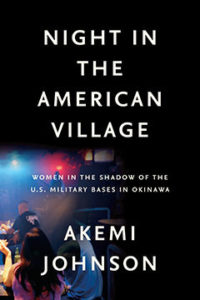

From Night in the American Village: Women in the Shadow of the U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa. Used with the permission of the publisher, The New Press. Copyright © 2019 by Akemi Johnson.