Please Stop Asking How I Wound Up in Fargo

Jung Yun on Answering the Same Questions for 25 Years

In 1996, Joel and Ethan Coen released Fargo, a black comedy about a kidnapping in the American heartland that would later go on to win seven Academy Awards. Until its release, my hometown had been a quiet, anonymous place to grow up. Few people I met on the East Coast had ever visited Fargo, let alone the state of North Dakota. Even fewer seemed interested in learning more. But then the film came out, and everything changed.

People who had seen the movie always started out wanting to know the same things: what did I think of it? (not much), and is it really that cold up there? (yes). Sometimes, in an attempt to be funny, they asked these questions in the exaggerated “Norwegian nice” accent made famous by the movie, punctuated with its dontchas and y’knooows.

A year after the movie came out, I was interviewing for a job in New York with a man whose office had a sweeping view of Central Park. When he asked where I grew up and I told him, he looked at me curiously.

“You mean like the movie?”

I was 25 years old and desperate for this man to like me, to hire me for a job that felt so far removed from the yellow and white–striped trailer that had been my family’s first home in Fargo. My resume was sitting on the table between us, detailing the education my parents had paid dearly for so I could one day sit in a tony office like his. But instead, we were talking about a movie that made Upper Midwesterners out to be a punchline, albeit ironically.

“You know that wasn’t even about Fargo,” I said casually, trying to ward off one of the common misconceptions about the movie, which had actually been set and filmed in Minnesota.

Until its release, my hometown had been a quiet, anonymous place to grow up.“I hated that movie,” he said.

“You did?”

He nodded. “You know that scene when the woman was blindfolded and trying to run away?”

I remembered it vividly—poor Jean Lundegard, barefoot in the snow outside the kidnappers’ hideout, yelping like a wounded animal in her purple cardigan and pink sweatpants.

“She was scared, and the kidnappers were just laughing at her.” He shook his head. “Everyone in the theater was laughing too. I didn’t see what was so funny about that.”

I paused, not certain if I should reciprocate and tell him what I hated about the movie—how it kept coming up in conversation, how its moment in the zeitgeist simply wouldn’t fade, how opening the door to one innocent question always seemed to invite more invasive ones: So how in the world did you end up in Fargo? Were you adopted or something? Not many Asians in North Dakota, are there? It always seemed especially cruel to me that when the only Asian American character in the film dissolved into a puddle of tears about his crushing loneliness, the combination of the actor’s exaggerated awkwardness and Minnesotan accent earned belly laughs throughout the theater.

So how in the world did you end up in Fargo? Were you adopted or something?With its snowy landscapes and pale, dough-faced actors, Fargo captured the whiteness of the area I grew up in, stamped it with the name of my hometown because the actual town where it was set—Brainerd, Minnesota—didn’t sound right to the Coens, and then spun it all into wide release. In doing so, it took a place that few people had ever heard of and turned it into a place that many wanted to know more about. With the loss of anonymity came questions that confirmed something I’d always suspected but never understood with such clarity: that my non-white presence in Fargo was strange and unexpected, something people wanted to puzzle over and interrogate.

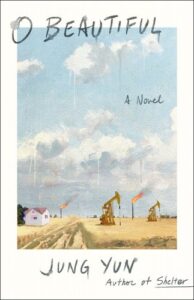

Scrutiny as a state of being is one of the topics that I chose to explore in my second novel, O Beautiful, about a biracial Korean American journalist who returns to her home state of North Dakota during the height of the oil boom, only to find it transformed by tens of thousands of oil workers (mostly men). The main character struggles with the weight of the male gaze and the skepticism of long-time residents who have always treated her like an outsider, all while chasing the story of a lifetime that unexpectedly connects to her own past.

“I didn’t like that movie either,” I finally said.

I remember looking at the view of the park again, wondering what more I’d have to say to finally change the subject.

Thankfully, I didn’t have to. The man moved on without asking the usual follow-up questions, the kind that implied that some people belong in certain parts of the country and other people didn’t.

I got the job, by the way. And 25 years after the film’s release, I still get the questions.

__________________________________

Jung Yun’s latest novel, O Beautiful, is available now from St. Martin’s Press.