Philip Roth was America’s most revered novelist of the postwar period and living proof of the idea that American novelists are most vivid when they write of place. Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1933 to a homemaker and an insurance salesman, and he returned over and over again to this period in his writing, from his National Book Award-winning debut, Goodbye, Columbus (1959), to Patrimony (1991), a memoir of his father, and American Pastoral (1997), a Pulitzer Prize-winning tale of the generational conflicts that churned within families and communities during the countercultural revolution of the 60s. Roth’s breakthrough, Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), the mock confession to an analyst of a sex-obsessed young Jewish man, made him wealthy, a luminary, and a lightning rod for feminists. Roth continued publishing through the haze of this notoriety, and in 1979 introduced his most beloved alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, with the perfect novel The Ghost Writer. Zuckerman narrates or plays a part in eight other Roth novels, from the postmodernist dazzler The Counterlife (1986) to the elegiac Exit Ghost (2007).

Like Don DeLillo and Saul Bellow, Roth dedicated his seventies to developing a late style, which he carried into four novella-length fictions that focus on mortality, morality, and the persistence of desire in spite of both. During this period, he began speaking more publicly about his work. In 2012, as the Library of America neared the end of publishing his books in uniform editions, Roth announced his retirement from writing and said he would not give another interview.

![]()

May 2006

No American novelist knows his craft better than Philip Roth. But in the past decade, as he turned out a series of strikingly vital novels about American history and became, at 70, a bestseller all over again, Roth apprenticed himself to a form new to him: the eulogy. “It’s not a genre I wanted to master,” says the writer, dressed in a black sweater and blue Oxford shirt, at the Manhattan offices of his literary agent. “I’ve attended funerals of, let’s say, four close friends, one of whom was a writer.” He wasn’t prepared for any.

“The plan goes like this,” he explains. “Your grandparents die. And then in time your parents die. The truly startling thing is that your friends start to die. That’s not in the plan.” Roth says this experience prompted him to write Everyman. The action opens at the funeral of its unnamed hero and then backtracks to give us the man’s life story. In many ways, Everyman is not a typical Roth character. He works in advertising and remains a faithful father and husband for long stretches of time. “I wanted a man who was in the mainstream,” says Roth. “So [this guy] attempts to lead a life within the conventions, and the conventions fail him, as they do conventionally.”

Over time, as his body breaks down, Roth’s character leaves his marriage, falls out with his brother, and ultimately quits his job in advertising to spend his retirement painting. All the while his body clock is ticking away. In fact, the novel, which Roth once called The Medical History, could be read like a fleshed-out physician’s chart. “As people advance in age,” says Roth, who turned 73 in March, “their biography narrows down to their medical biography. They spend time in the care of doctors and hospitals and pharmacies, and eventually, as happens here, they become almost identical to their medical biography.”

“Your grandparents die. And then in time your parents die. The truly startling thing is that your friends start to die. That’s not in the plan.”In numbers alone, Roth has hit upon a winning conceit. The population of America is getting older, and questions of health—and mortality—are on their minds. Jerome Groopman, a medical columnist for The New Yorker and a professor at Harvard Medical School, says Roth “clearly did his homework when it came to many of the clinical aspects.” Several operating scenes are described in detail, as are the technicalities of procedures. But Groopman believes there’s much more to the novel than that. “The meat of the book, the heart of it, is the story of this man and the human condition, and the mistakes we make through life—how these then come back and are shown to fail to protect us from the fear and loneliness of facing mortality.”

In this fashion, the novel draws upon the 15th-century morality play Everyman, in which a vigorous young man meets Death upon the road. “Everyman then utters what is perhaps as strong as any line written between the death of Chaucer and the birth of Shakespeare,” says Roth, savoring the language. “Oh, Death, thou comest when I had thee least in mind.” Roth’s hero has a series of these moments. In his childhood, he nearly dies from a burst appendix. In his youth, he has an epiphany while standing on the beach. “The profusion of stars told him unambiguously that he was doomed to die,” reads one passage.

Roth has written of mortality before. He addressed the topic with pathos in his National Book Critics Circle Award–winning memoir Patrimony, and with hysterical humor in his novel Sabbath’s Theater, which won him a second National Book Award. The last line of that book read: “How could he leave? How could he go? Everything he hated was here.” Everyman, however, has none of these hyperbolic flourishes. “It’s extremely dark,” says the poet Mark Strand, a friend of Roth’s for more than forty years, “and really unalleviated by the usual high jinks and humor that Roth is able to inject into novels.”

It will be interesting to see whether Roth’s readers will follow him into this dark territory. His previous novel, The Plot Against America, reportedly sold ten times as many copies in hardcover as the books that preceded it. Grateful but chagrined, Roth refuses to let this fact buoy him. “Well, it doesn’t change my opinion of the cultural facts,” he says. “If it’s this book or Joan Didion’s book that strikes the fancy of people, it doesn’t change the fact that reading is not a source of sustenance or pleasure for a group that used to read for both.”

Roth’s writing method has not changed in decades. “I write the piece from beginning to end,” he says, explaining how he works, “in drafts, enlarging it from within, which means I tend not to work by adding on. I have the story, and what I find I need to develop is stuff within the story that gives it the punch, that thickens the interest.”

When Roth reaches a point where he can do no more work, he takes the manuscript to a select group of early readers. “And then I’ll go and sit down with them for three or four hours, however long it takes, and listen to what they have to say. For much of it I don’t say anything. Whatever they say is useful. Because what I’m getting is somebody else’s language about my book. That’s what’s useful. What they do is break the book open, they shatter it, and I can go back in for one last attack.”

The novelist Paul Theroux, who read the book “in one sitting” and then again “with even more pleasure and admiration,” says that Roth’s careful consideration of his story’s effect shines through. “Something I admire greatly is Roth’s apparent casualness—in reality his effects are carefully built up.” In this case, Roth’s ability to work without his usual stunts is what makes the novel so impressive to Theroux. “Its power arises from . . . its persuasive detail, its fully realized and recognizable people, their weaknesses especially.”

In the past, Roth has written autobiographically enough that it is tempting to confuse him with his characters—and their weaknesses. During the 60s, when Portnoy’s Complaint was racking up half a million copies in sales, even Jacqueline Susann, author of Valley of the Dolls, joked she would like to meet him but wasn’t sure she’d like to shake his hand. Everyman has its share of Roth moments—Everyman is remarkably virile into his seventies, for example—but they tend to be of a tender biographical note. The opening scene alludes to the funeral of Roth’s close friend and literary mentor, Saul Bellow. Later, after several operations, Roth’s character calls his friends who are ill themselves to say goodbye.

Finally, the character visits the grave of his parents and meets the man who probably dug their grave. “That is almost certainly based on Roth’s experience,” says Strand. “Nothing is lost on Philip; whatever he can use, he’ll use.”

Still, it would be a mistake to think that Roth is contemplating the end with shaky hands. In person, the novelist appears fit and hale, arriving at the interview with a duffel bag like a man who has just returned from the gym. His gaze is powerful and intense. Death does not frighten him. The book “wasn’t on my mind because of my own death, which I don’t think is—I hope isn’t—imminent,” he says, laughing. Even when Roth had open-heart surgery in 1988, he didn’t think twice about the end. “Well, I never believed I would expire. I was pretty sure these guys knew what they were doing, that they would fix me up, and they did.”

“He’s had physical setbacks,” Strand says, “but he began much stronger and more athletic than the rest of us. When I met him he was a terrific baseball player: He could hit the ball a mile. And intellectually, he’s one of the most alert people I’ve ever met. He serves up stories that are just mesmerizing and hilarious.”

“When I was a kid,” says Roth, “because my father was in the insurance business, he had actuarial booklets, and I knew women lived to be 63, men to be 61. Now I think it’s 73. It hasn’t changed dramatically when you think of all the medical progress of the postwar era.”

Groopman sees a certain sad truth in this. “There is a very prevalent illusion with all the technology we have . . . there is this sense that we should have control over our clinical outcome.” But, as Roth’s hero finds out, as we all do, that’s not the case.

“The contract is a bad contract and we all have to sign it,” Roth quips grimly. In nineteenth-century fiction like Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, awareness of life’s end sent characters reaching to God. Not for Roth’s Everyman. Or for its creator: “Nothing will force my hand,” he says.

![]()

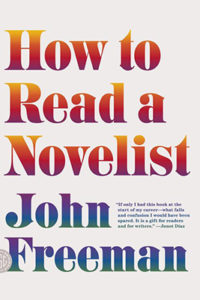

From How to Read a Novelist. Used with permission of FSG Originals. Copyright © 2013 by John Freeman.