Personal Loss and Public Grief in the Aftermath of the Las Vegas Shooting

John Branch on the Way We Move On Even As We Mourn

I was on the sideline of a soccer field two Saturdays ago, watching my 12-year-old daughter and her Novato teammates. I don’t remember much about that game, but Novato won, and one of the goals was scored by the smallest girl on the team, a quick and feisty forward who wears a long ponytail and jersey number 8. We whooped and cheered her name. I found out later that her parents weren’t there that afternoon. They were in Las Vegas for a getaway weekend.

About 36 hours later, I was on my way to Las Vegas myself, rushing to join my New York Times colleagues to cover the latest mass shooting, maybe bigger than them all. I hadn’t covered one of them since 1999, when I was in the wrong place at the right time and rushed into the aftermath of Columbine.

A colleague of mine and I checked into a massive suite at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, 11 floors directly below that of the shooter. It had the same view of the concert ground across the Strip, where investigators in the daylight were picking through the carnage of the night before. That was about when my wife sent me a text. That little soccer player’s mom was at the concert the night before, she said. She’s missing.

But Stacee Etcheber was not my story. The gunman was. I spent a week mostly about one hundred feet below where the shooter committed mass murder, trying to solve the mystery of what he’d done. I talked to people, followed every lead and wrote stories. It’s what reporters do. It was a news story, as horrific as they come, and we’re trained to keep our emotional distance from the things that we cover.

Late that night, I stood in front of the window, just like the one that a madman broke eleven floors above and used as a perch to shoot hundreds of people he did not know. The body count was on its way to 58. I thought about home.

Stacee’s family soon announced that she had died. My wife and I didn’t really know Stacee much—obviously not well enough to notice that she was not among the few dozen people at a rec-level girls’ soccer game. But some of our closest friends were dear friends of hers, and our town is small enough that there was probably no more than two degrees of separation to the family.

One of the goals was scored by the smallest girl on the team, a quick and feisty forward who wears a long ponytail and jersey number 8.My family was among the hundreds of people, friends and strangers, who crowded onto the grounds of an elementary school and held candles aloft during the vigil. My daughter was one of the dozens of kids who solemnly held roses in her honor, and she hugged her classmate and teammate when it ended. She and a couple of friends made a cake and delivered it to the Etchebers’ house the next day.

Orange was Stacee’s favorite color, and on Friday, after people bought as much orange ribbon as they could find at all the local craft stores, an army tied ribbons all around town, from the trees on downtown’s Grant Avenue to the posts in front of Pioneer Park. My wife and her friends tied them around the trees in front of the middle school where Stacee’s daughter goes to school, along with mine.

I missed it all. I was as close to the site of the shooting as you could get, and yet felt fully disconnected from the effect of the tragedy. One night I walked to the memorial that sprang up in the median of South Las Vegas Boulevard, the kind of now familiar post-shooting memorial that I saw at Columbine almost two decades before, with balloons and flowers and candles. I found a photo of Stacee that had been placed in the middle of it all, and took a picture and sent it home.

In Las Vegas, Stacee was just one in a crowd, part of a list. But she and her family were all anyone talked or thought about back in Novato, and that is where I got my news. I heard that Stacee’s husband, a San Francisco police officer, was running with Stacee through the barrage of gunfire when he stopped to help someone; he told his wife to go on and never saw her alive again. I heard that television news trucks were parked in front of the house. I heard stories of friends pulling over in their cars to cry at the weight and nearness of it all. There were beautiful and crushingly sad Facebook posts in Stacee’s honor, the kind you see after every tragedy, except these were written by people I knew well.

I heard my wife, who grew up in a nearby town, tell me that she had never been more proud to call Novato home.

I checked out of that Mandalay Bay suite on Saturday morning, excused from reporting duties, and flew home in the hopes of making my daughter’s soccer game. I found the red rose from the vigil, starting to fade and wilt, in a vase on the kitchen counter. When we got to the game, we and the other parents were somewhat surprised to see Stacee’s husband and extended family there, too. Warming up with the girls was number 8, with her long ponytail.

We all wore orange ribbons, attached by safety pins, including the girls on both teams. The Novato team wore orange armbands with the initials “S.E.” Before kickoff, both squads came across the field to the spectator side and lined up in straight lines. Our team’s coach asked the parents to stand for thirty seconds of silence. And then two of the league’s better teams played a rather meaningless soccer game, only this one felt about as meaningful as anything I’ve ever watched.

And it was late in the second half when the ball suddenly swung from one end to the other, and Stacee’s daughter gave chase through three retreating opponents and beat them all to the ball. And in one blink-and-you-missed-it moment, she booted the ball into the corner of the net for what held on as the winning goal.

Her teammates chased her and swarmed her, and they and she looked as free and happy as girls can be on a sunny fall Saturday afternoon with their friends. The parents jumped and cheered as loudly as I’ve heard parents cheer at a kids’ soccer game. Behind my sunglasses, I was bawling. It was the first time I’d cried all week.

__________________________________

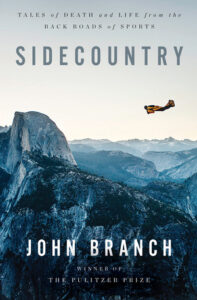

Excerpted from Sidecountry: Tales of Death and Life from the Back Roads of Sports. Copyright (c) 2021 by John Branch. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.