The Balloon-Hoax of Edgar Allan Poe and Early New York Grifters

John Tresch on the Advent of Extreme Publicity

On April 13, 1844, two days after the closing of the National Institute’s gala in Washington, the front page of the New York Sun barked out,

ASTOUNDING NEWS! BY EXPRESS VIA NORFOLK! THE ATLANTIC CROSSED IN THREE DAYS! SIGNAL TRIUMPH OF MR. MONCK MASON’S FLYING MACHINE!!!

Below the headlines the article gushed, “The great problem is at length solved! The air, as well as the earth and the ocean, has been subdued by science.” Other exclamations peppered the columns: “God be praised! Who shall say that anything is impossible hereafter?”

It was astonishing news: the first successful air balloon flight across the Atlantic. The chief aeronaut was Monck Mason, an Irish adventurer and science writer who in 1836 had sailed in a hot-air balloon from Wales to Germany.

The flight from England to Charleston, South Carolina, was made possible by Mason’s technical improvements: a device to control the balloon’s height, a guide rope serving as a regulating ballast, and a rudder of cane and silk. The Sun included the onboard journal of another famous man of science, Harrison Ainsworth, detailing technical challenges the “rapturous” journey faced; the remarkable machine was shown in a detailed woodcut. The Sun obtained the exclusive story thanks to “the energy of an agent at Charleston”—alluding to its extraordinary means of getting news quickly, including special express trains, carrier pigeons, and the electromagnetic telegraph of Morse.

The article ended with an awestruck prophecy: “What magnificent events may ensue, it would be useless now to think of determining.” No need to think: just buy another copy for your friends!

The presentation of astonishing new discoveries, accompanied by controversy, was being tuned to a fine art—as part of a powerful if chaotic machine of publicity, doubt, and belief.In actual fact, the only real journey was experienced by The Sun’s readers: they had been taken for a ride. The story was a hoax, written by Poe, who had arrived in the city a week earlier. But, he later said, there was “nothing put forth in the Balloon-Story which is not in full keeping with the known facts of aeronautic experience”; any part of it, he insisted, might “really have occurred.”

In an essay exposing the hoax one month later, he wrote that the public response was “a far more intense sensation than anything of that character since the ‘Moon-Story’ of Locke.” From sunrise until 2:00 p.m. on the day of the publication “the whole square surrounding the ‘Sun’ building was literally besieged.” He quoted a New Yorker waiting for an “extra” edition: “As soon as the few first copies made their way into the streets, they were bought up, at almost any price, from the news-boys, who made a profitable speculation,” some selling for half a dollar. The story was republished as a single-sheet broadside “extra”; The New York Herald’s reporter was indignant at this “attempt to hoax” for being “blunderingly got up,” while the Saturday Courier reported that around “50,000 of the extras were sold.”

For Poe, the hoax’s reception provoked intriguing reflections: “The more intelligent believed, while the rabble, for the most part, rejected the whole with disdain.” He saw this as a historical change: “20 years ago credulity was the characteristic trait of the mob, incredulity the distinctive feature of the philosophic,” but the positions had reversed. “The wise are disinclined to disbelief—and justly so.” Though there were certainly frauds and false claims, the age was so crowded with astonishing discoveries and inventions that the most intelligent course was now to believe first and ask questions later.

Poe’s balloon hoax was a perfect calling card for his arrival in New York. There the presentation of astonishing new discoveries, accompanied by controversy, was being tuned to a fine art—as part of a powerful if chaotic machine of publicity, doubt, and belief.

*

Luck was on his side when he arrived on April 6. It was raining at the docks; scurrying ashore, he found a boardinghouse and returned with an umbrella to hold over Virginia, who “coughed none at all” as she stepped ashore. Their residence on Greenwich Street was stocked with a table from a fairy tale, as he told Maria Clemm: for dinner they had “the nicest tea you ever drank, strong & hot—wheat bread & rye bread—cheese—tea-cakes (elegant) a great dish (2 dishes) of elegant ham, and 2 of cold veal, piled up like a mountain and large slices—3 dishes of the cakes, and every thing in the greatest profusion. No fear of starving here.”

Even so, Virginia “had a hearty cry last night,” missing her mother and Catterina, the family’s tortoiseshell cat. He reassured Muddy, who would join them soon, “I feel in excellent spirits & have’nt drank a drop—so that I hope soon to get out of trouble.”

New York was the largest city of the United States. Its docks heaved with goods for sale and throngs heading west on the Erie Canal. Advertising pitches and sellers’ cries came from all directions, along with the racket of coal wagons on cobblestones. Poe was struck by the noise. “Where two individuals are transacting business of vital importance, where fate hangs upon every syllable and upon every moment—how frequently does it occur that all conversation is delayed, for five or even ten minutes at a time,” until “the leathern throats of the clam-and-cat-fish-venders have been hallooed, and shrieked, and yelled, into a temporary hoarseness and silence!” Maria Clemm joined them in the boardinghouse, close to the booksellers, magazine offices, and printers on Ann Street, well below the mansions recently sprung up along Fourteenth Street but a short walk to Broadway, City Hall, and the abject slums of the Five Points neighborhood.

Reading rooms and libraries abounded; the city had more journals and publishing houses than any other. Amid the chatter, there was plenty of respectable science in New York. The Lyceum of Natural History, founded in 1817, boasted an excellent collection of preserved animals, plants, and rocks. In 1836 it purchased a large building on Broadway near Prince Street, renting rooms to the Phrenological and Horticultural Societies, its opening celebrated with a geology lecture by Benjamin Silliman. The lyceum’s leading lights included John Torrey; his assistant, the botanist Asa Gray; the storm theorist and engineer William Redfield; and John W. Draper, continuing his work on chemistry, physics, and the daguerreotype. The lyceum’s building was repossessed in 1843, but Draper helped to relocate it in NYU’s medical building.

Yet the voice of sober fact and practical utility could be drowned out in the city’s cacophony of entertainments, sensational news, and radical science. At Niblo’s Garden on Broadway at Prince Street, one could enjoy dinner, plays, music, panoramas, scientific lectures, and the prestidigitations of Antonio Blitz, a celebrated stage magician. At the Society Library on Broadway—where Thomas Cole’s large allegorical paintings The Voyage of Life were hung—lecturers in philosophy, literature, and the arts filled the bill.

A few blocks east of Washington Square, the imposing Clinton Hall— where Dionysius Lardner launched his American career—was the headquarters of a vegetarian society, a suffragist group, and one of the largest intellectual concerns in the country: the Phrenological Society. Run by Orson and Lorenzo Fowler, it held a collection of skulls and busts, a lecture hall, printing office, and reading room in which to learn about bumps, organs, and social reform. In Clinton Hall, lectures of confirmed and established science and solid learning vied with new theories and systems, some of them wild speculations, others outright frauds, while still others hovered uncertainly between the factual, the provocative, and the apocalyptically urgent.

The author of Humbugs of New-York declared the city “the chosen arena of itinerating mountebanks, whether they figure in philosophy, philanthropy, or religion,” in a race to the bottom: “The more ignorant, impudent, and even vicious, such charlatans proclaim themselves to be, the greater power and patronage they may expect.” Several journals spoke to and on behalf of the masses. Horace Greeley’s Tribune published the popular astronomical lectures of Ormsby Mitchel, the West Point mathematician and colleague of Bache’s who had founded the Cincinnati Observatory. The Tribune also published translations of Charles Fourier, the French utopian socialist. Fourier sought to reformulate society on the basis of a more rational and passionate distribution of labor (though his advocacy of a mind-boggling variety of sexual arrangements was abridged for American sensibilities).

He constantly shifted his positions; in his writings the pursuit of truth was accompanied by the play of glitter and shadow.Daily newspapers had first sprung up as commercial bulletins announcing commodity prices and the arrival of ships. The Sun, where Poe published his balloon article, was the first large broadsheet read by those who could not afford subscriptions or sixpenny dailies. Since starting in 1833, it grew through the “newsboy system” and the success of Richard Locke’s “Moon Hoax.”

Another hoaxer, Phineas Taylor Barnum, had recently become the owner of the American Museum on Broadway, just below City Hall Park. The building was adorned with flags, a lighthouse lamp, and a rooftop garden for views and balloon launches. The son of a shopkeeper, Barnum hailed from Bridgeport, Connecticut. With a mop of dark curly hair, large eyes, a booming voice, and a captivating flow of balderdash, he speculated in real estate and launched a lottery network before dedicating himself to popular entertainments.

In 1837 (while Poe was plotting the mystifications of Pym), Barnum met one of his heroes at Boston’s concert hall: Johann Maelzel, on tour with his chess-playing automaton. Barnum was promoting his own first successful attraction, modestly labeled “The Greatest Natural and National Curiosity in the World.” This was Joice Heth, a wizened woman he claimed was a former slave and George Washington’s nanny, making her more than a century and a half old. Heth smoked cigars and regaled audiences with the infant antics of “the father of our country.” For doubters, Barnum presented a bill of her purchase and an affidavit that “eminent physicians and intelligent men” from around the country “examined this living skeleton and the documents accompanying her, and all invariably pronounce her to be as represented 161 years of age!” Maelzel, “the great father of caterers for public amusement,” approved of Barnum’s dehumanizing spectacle and assured him of future success: “‘I see,’ said he, in broken English, ‘that you understand the value of the press, and that is the great thing. Nothing helps the showmans like the types and inks.’”

Barnum kept his attractions in print. His rotating list of curiosities included giants, albinos, Native American dancers, jugglers, magicians, automata, stuffed animals, fossils, and monstrous creatures. As he had done with Joice Heth, he counted on viewers’ eagerness to gawp at other humans, especially if they were set apart as exaggeratedly different from themselves. One of his most famous performers was Charles Stratton, or Tom Thumb—“the smallest person that ever walked alone”—a child dwarf said to be decades older than he was, trained to talk and move like an adult, drinking and smoking cigars by age five. Some of the wonders were genuine; many were exploitative frauds; all were open to questioning and debate.

Barnum’s “Grand Scientific and Musical Theater” hit its stride with an exhibit inspired by the U.S. Exploring Expedition, which docked in New York in 1842 after its four-year voyage around the globe. The onboard death of the captured Fijian chief, Veidovi, was much discussed in the news. When word spread of the lurid plot to preserve his head for Morton’s craniological examination, Barnum added a new attraction to his museum’s handbills: “the head of the cannibal chief.” Visitors discovered, after paying, a plaster cast of the dead man.

To feed the “Feejee fever,” Barnum borrowed a Japanese curiosity from a showman in Boston, Moses Kimball; renaming it the “Feejee Mermaid,” he announced the upcoming arrival of an English scientist, “Dr. Griffin, agent of the Lyceum of Natural History in London, recently from Pernambuco.” The famous doctor—actually Barnum’s associate Levi Lyman—appeared at the New York Concert Hall on Broadway and displayed the mermaid, without mentioning Barnum—who then announced that he had purchased “the curious critter” and would be showing it at his American Museum.

In the month after the Feejee Mermaid’s arrival, the museum’s ticket revenues tripled from about one thousand to more than three thousand dollars per week. Doubts about the chimerical “Dr. Griffin” and the mermaid, “regarding which there has been so much dispute in the scientific world,” were part of the attraction. Some said the creature had been captured alive in the Fiji Islands; others declared it “an artificial production, and its natural existence claimed to be an utter impossibility.”

Barnum struck a pose of open-minded neutrality. He “can only say” that the mermaid has “such appearance of reality as any fish.” But who, he asks, “is to decide when doctors disagree”? The paying audience, of course: you decide. Whether it was “the work of nature or art,” the object was “the greatest Curiosity in the World.” Barnum took the mermaid on the road. In South Carolina the controversy led to threats of a duel between a minister-naturalist and a newspaper editor; Charleston residents feared “mob violence.”

This ugly fracas—and Barnum’s handsome profits—arose from a “mermaid” that closer inspection revealed as the leathery upper body of a monkey sewn onto the tail of a preserved fish. Yet it was not a simple case of an exhibitioner trying to pass off a forgery as an authentic specimen. Barnum staged not only the specimen but also the controversy—the more involved and protracted, the better. At Charles Willson Peale’s museum in Philadelphia, natural wonders such as the mastodon’s skeleton had been introduced as authoritative facts. True to their father’s Enlightenment legacy, Peale’s sons presented a specimen similar to the Feejee Mermaid but pointed out its stitches, explaining exactly how it had been made. Barnum’s shows, instead, invited viewers to make up their minds for themselves.

Barnum’s exhibitions were among the most important routes through which working-class audiences learned about natural history and popular mechanics. Amid the fakes and provocations were wonders and facts: exceptional geological specimens, rare plants and animals, fossils, clever inventions, demonstrations of natural history, chemistry, and astronomy. In this version of antebellum science, knowledge was experienced and felt, at the price of a cheap ticket. It was open to disagreement, debate, speculation, and grinning exploitation.

Barnum was advancing an extreme form of the “charlatanism” that Bache and Henry saw as the enemy of their scientific aims. While he diffused uncertainty and disagreement among a broad audience, they aimed to concentrate scientific certainty and authority in a few hands. For Bache and Henry, any public display of science risked being dragged down to the level of a carnival, jubilee, revival, or town hall meeting. Worst of all from their perspective, Barnum encouraged his low-paying crowds to think that their opinions mattered in questions of scientific truth.

The conditions of persuasion were changing in the United States, through the expansion of commercial culture, high-intensity evangelism, and the regular combat of political campaigns. Much of the testing of beliefs took place in face-to-face public meetings: political speeches, religious revivals, science lectures, stage magic. The press was the indispensable accelerator, reaching unequaled speeds in New York. Bache and Henry sought fortified bulwarks against this rising current, while Barnum gleefully hastened it forward and rowed along. Poe’s strategies were at times those of Bache, at times those of Barnum. Pushed by poverty and the threat of starvation, he constantly shifted his positions; in his writings the pursuit of truth was accompanied by the play of glitter and shadow.

__________________________________

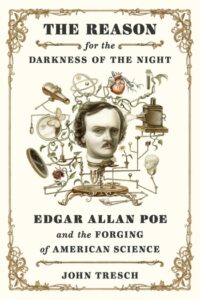

Excerpted from The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science by John Tresch. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by John Tresch.