Paul Auster on One of the Most Astonishing War Stories in American Literature

Considering the Dark Horrors of Stephen Crane’s “An Episode of War”

On the last day of October 1895, a letter was sent to Stephen Crane by the corresponding editor of The Youth’s Companion inviting him to submit work to the magazine: “In common with the rest of mankind we have been reading The Red Badge of Courage and other war stories by you… and feel a strong desire to have some of your tales.” Advertising itself as “an illustrated Family Paper,” the Companion was a national institution with an immense readership that began its life in 1827 and remained on the American scene for more than 100 years. Never more popular than in the 1890s, it published work by every important writer from Mark Twain to Booker T. Washington, and, as the corresponding editor pointed out in his letter to Crane, “the substantial recognition which the Companion gives to authors is not surpassed in any American periodical.” On top of that, it paid well.

Crane was hard at work on The Third Violet just then, but he wrote back on November fifth to say that he “would be very glad to write for the Companion” and promised to send them something “in the future.” The future arrived in March, when he mailed off the manuscript of “An Episode of War” to the offices in Boston, mentioning in the last line of his cover letter that “this lieutenant is an actual person”—possibly someone he had heard about from his uncle Wilbur Peck, who had served as an army doctor during the war.

The shortest of Crane’s Civil War stories from 1895–96, “An Episode” is also the strongest, the boldest, and the most moving—a thoroughly modern work that takes on the issue of war trauma with pinpoint clarity and perceptiveness. The condition has been a part of human life ever since the first war was fought between battling clans thousands of years ago, and even though it has gone by several different names in America over the course of our history—soldier’s heart during the Civil War, shell shock during World War I, war neurosis during World War II, and post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) during the Vietnam War and on through subsequent wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere—its symptoms have never varied, and the affliction is the same one in all wars, repeated again and again in an eternal pattern of inner brokenness and wordless suffering.

The story begins in mid-action as the lieutenant (never named) is conscientiously dividing up and distributing coffee rations to each squad in the regiment. “Lips pursed,” “frowning and serious,” he is using his sword to separate the mass of coffee beans spread across his rubber blanket into squares that are “astoundingly equal in size,” and just as he is about to finish this “great triumph in mathematics,” with various corporals still thronging around him to claim their allotted shares, the lieutenant cries out in pain, looks at the man next to him “as if he suspected it was a case of personal assault,” and an instant after that, when the others notice blood on the lieutenant’s sleeve, they cry out as well. No, the lieutenant has not been punched by a fellow soldier; he has been struck by an enemy bullet.

So ends this astonishing piece of work, which to my mind is one of Crane’s most brilliant little stories.

Crane has managed to tell all this in a mere six sentences, and now, with dozens of narrative options before him, he hunkers down over the next two paragraphs and minutely examines the immediate responses of both the lieutenant and the men to this abrupt, wholly random event, “this catastrophe which had happened when catastrophes were not expected.” No one says a thing. The lieutenant, clearly beginning to go into shock, looks out over the breastwork and stares at the green woods in front of him, which are now dotted with “many little puffs of white smoke.” After a moment, the still-silent men look there as well and contemplate “the distant forest as if their minds were fixed upon the mystery of the bullet’s journey.” The silence is crucial, and Crane prolongs it for an almost unbearable length of time, stretching it out because he is writing about a world in which soldiers are supposed to be shot in battle, not when they are distributing coffee beans to other soldiers, and the mystery of that silent, invisible bullet is powerful enough to stun the witnesses into a state of speechless awe. As for the man who was hit, he has entered a zone in which words are utterly beyond him.

Then comes the intricate business of what to do with the sword. The lieutenant’s right arm is immobilized, and therefore he has transferred it to his left hand, grasping it not by the hilt but somewhere along the middle of the blade, “awkwardly,” and all at once that familiar object, which is the very emblem of his soldierhood, has become strange to him. This is one of the purest examples of Crane’s ability to explore emotions through inanimate things, and by focusing his attention on the sword, he leads us through the lieutenant’s gradual dissociation from the reality he belonged to just minutes earlier, his growing detachment from what is now and will forever after be his former self as he withdraws into the isolating grip of what was then called soldier’s heart.

The process continues when the lieutenant tries to put the sword back in its sheath, an all but impossible task when the sword is in your left hand and the scabbard is on your left side, especially when you are holding the sword in the middle of the blade, and most especially when the sword has become strange and meaningless to you, and as the wounded man engages in a “desperate struggle with the sword and the wobbling scabbard he breathed like a wrestler.”

But at this instant the men, the spectators, awoke from their stone-like poses and crowded forward sympathetically. The orderly-sergeant took the sword and tenderly placed it in the scabbard. At the time, he leaned nervously backward, and did not allow even his finger to brush the body of the lieutenant. A wound gives strange dignity to him who bears it. Well men shy from this new and terrible majesty. It is as if the wounded man’s hand is upon the curtain which hangs before the revelations of all existence, the meaning of ants, potentates, wars, cities, sunshine, snow, a feather dropped from a bird’s wing, and the power of it sheds radiance upon a bloody form, and makes the other men understand sometimes that they are little…

There were others who proffered assistance. One timidly presented his shoulder and asked the lieutenant if he cared to lean upon it, but the latter waved them off mournfully. He wore the look of one who knows he is the victim of a terrible disease and understands his helplessness. He again stared over the breastwork at the forest, and then turning went slowly rearward. He held his right wrist tenderly in his left hand, as if the wounded arm was made of very brittle glass.

And the men in silence stared at the wood, then at the departing lieutenant—then at the wood, then at the lieutenant.

With these piercing formulations and precisely chosen narrative details, Crane delineates the lieutenant’s expulsion from the regiment that has been under his command. The alienating force of the wound has driven him into himself and out of the group, severing his ties with his comrades, and from now on he is a man alone, still in the war but no longer a combatant, invalidated out of the army even as he remains in uniform, and for the next two pages he wanders around in a kind of stupor as he searches for the field hospital, looking at the world as if he were a stranger from another universe, curious but indifferent, cut off from the meanings of things that until now have meant everything to him. When he sees a general mounted on a black horse, for example, and then watches an aide gallop up to him “furiously” and present him with a piece of paper, it was, “for a wonder, precisely like an historical painting.”

The shortest of Crane’s Civil War stories from 1895–96, “An Episode” is also the strongest, the boldest, and the most moving.

Later on, when he sees the swirling, thunderous charge of a battery off to his right, with shouting men on horseback and “the roar of wheels” and “the slant of the glistening guns,” he simply watches—emotionless, walled off, elsewhere. Some stragglers tell him how to find the field hospital, and a few minutes later he is approached by an officer who begins to scold him for not taking proper care of his arm. The officer then “appropriated the lieutenant and the lieutenant’s wound,” cutting the sleeve and bandaging the exposed tissue and mangled flesh with a handkerchief, rattling on in a tone that “allowed one to think he was in the habit of being wounded every day. The lieutenant hung his head, feeling, in this presence, that he did not know how to be correctly wounded.”

At last he makes it to the low white tents surrounding an old schoolhouse that serves as the makeshift hospital, a muddy, clamorous place where two ambulance drivers have interlocked wheels and are shouting at each other, while inside the ambulances, “both crammed with the wounded, there came an occasional groan,” and outside “an interminable crowd of bandaged men” shuffles past as another dispute breaks out on the schoolhouse steps and the lieutenant looks at a man sitting with his back against a tree smoking a corncob pipe—his “face as grey as a new army blanket,” a silent, wounded soldier easing himself into the arms of death. No more than that—a single, haunted image—and then Crane pushes on to the end of the story, with its enormous, startling leap between the last two paragraphs:

A busy surgeon was passing near the lieutenant. “Good morning,” he said with a friendly smile. Then he caught sight of the lieutenant’s arm and his face at once changed. “Well, let’s have a look at it.” He seemed possessed suddenly of a great contempt for the lieutenant. This wound evidently placed the latter on a very low social plane. The doctor cried out impatiently. What mutton-head had tied it up that way anyhow. The lieutenant answered: “Oh, a man.”

When the wound was disclosed the doctor fingered it disdainfully. “Humph,” he said. “You come along with me and I’ll ’tend to you.” His voice contained the same scorn as if he were saying: “You will have to go to jail.”

The lieutenant had been very meek but now his face flushed, and he looked into the doctor’s eyes. “I guess I won’t have it amputated,” he said. “Nonsense, man! nonsense! nonsense!” cried the doctor. “Come along, now. I won’t amputate it. Come along. Don’t be a baby.”

“Let go of me,” said the lieutenant, holding back wrathfully. His glance fixed upon the door of the old school-house, as sinister to him as the portals of death.

And this is the story of how the lieutenant lost his arm. When he reached home his sisters, his mother, his wife, sobbed for a long time at the sight of the flat sleeve. “Oh, well,” he said, standing shamefaced amid these tears, “I don’t suppose it matters as much as all that.”

So ends this astonishing piece of work, which to my mind is one of Crane’s most brilliant little stories, a four-page 60-yard dash run at full tilt from start to finish without a single misstep or stumble along the way, so perfect in its execution that it justifiably ranks as one of the finest war stories in American literature. The jump between the last two paragraphs lands with the force of an explosion, and there we find the one-armed lieutenant among his weeping relatives, a hollowed-out man devastated by the trauma of war who has become so diminished in his own eyes that he can’t even bring himself to regret the loss of his arm. To use Crane’s term, he has discovered that he is “little,” and why should the universe care about the subtraction of one little arm from the body of yet one more little man?

The Youth’s Companion read the story and paid Crane for the right to publish it, which effectively turned the magazine into the owner of “An Episode of War” and explains why it was not included as the seventh story in The Little Regiment, but after paying for the rights, the magazine began to have second thoughts and ultimately decided not to use it. The publication represented the American public, after all, and the editors felt that patriotic Americans would not look kindly upon such a dark representation of the realities of war. Sometime later, in an effort to recoup the money they had forked out for the story they had killed, they sold the British rights to a magazine called The Gentlewoman (!), where it was published in December 1899, six months before Crane’s death, which means that “An Episode” was never circulated among American readers in Crane’s lifetime.

Years passed, and in 1916 The Youth’s Companion dug into its dead-matter file, pulled out the story it had bought from the now long-dead Crane back in 1896, and published it in America for the first time. That was in the middle of the Great War, of course, and with articles from the trenches and hospitals about a new phenomenon known as shell shock everywhere in the world press, perhaps the current editors felt that Crane’s old story had at last become timely—and acceptable to the readers of their magazine. Lest we have forgotten, however, another year would go by before America entered the war, meaning that the story was published when American troops had not yet begun to suffer from the disease that had been ravaging their French and British allies since 1914. By the time the war ended, in November 1918, more than 30,000 of them had.

__________________________________

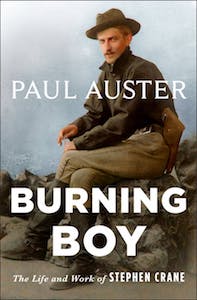

Excerpted from BURNING BOY: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane by Paul Auster. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2021 by Paul Auster. All rights reserved.

Paul Auster

Paul Auster is the bestselling author of 4 3 2 1, Winter Journal, Sunset Park, Invisible, The Book of Illusions, and The New York Trilogy, among many other works. He has been awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize for Literature, the Prix Médicis Étranger, the Independent Spirit Award, and the Premio Napoli. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.