Paul Auster: I Don't Even Know if The New York Trilogy is Very Good.

An Author Looks Back at His Most Well-Known Book

And whatever the man called each living creature, that was its name. (Gen. 2:19)

Inge Birgitte Siegumfeldt: The New York Trilogy is probably your most widely read book, principally, I think, because it breaks new ground through the unique combination of exploration, captivating story, and reflection that characterizes much of your work. The reader is at once drawn into the world of detection and obsessive surveillance only to find him- or herself thoroughly taken in by the existential and literary mysteries you put before us in the three short novels—City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room—that form the Trilogy. Jan Kjærstad is quite right to describe it as a “crystal that refracts light into colors that have rarely been seen before.” What prompted these strange stories?

Paul Auster: They come out of material I’d been thinking about and working on for many years. In The Red Notebook, I describe the phone call I received from the person who wanted to talk to the Pinkerton Agency. It triggered the first novel, City of Glass. The idea of a wrong number intrigued me and, because it happened to concern a detective agency, it somehow seemed inevitable that my story should have a detective element to it. It’s not in any way a crucial part of the story, and it was always irritating to me to hear these books described as detective novels. They’re not that in the least.

IBS: No, not at all. Even if the protagonist in each of the stories at some point devotes himself to an investigation, the element of detection here concerns linguistic and existential issues rather than criminal ones. Did you deliberately set out to experiment with the detective genre or was it simply useful to you as a form?

PA: It was useful to me in the same way old musical hall routines and vaudeville were useful to Beckett in writing Waiting for Godot. Or the way romances were useful to Cervantes in writing Don Quixote. You could also say Crime and Punishment is a detective story, I suppose. Many novelists have used crime fiction forms to write about other things. I’m hardly the first to do this. So, I didn’t feel I was setting out to explode anything. I was just curious.

IBS: I thought perhaps you wanted to cast writing here as a kind of detection?

PA: I just wanted to remain loyal to the inspiration prompted by that phone call. It was a challenge I set for myself. There are sources of much greater importance to this book. At a strictly intellectual level, one of them derives from my intense reading of John Milton when I was an undergraduate. I had a brilliant professor, Edward Tayler, who taught the famous Milton course at Columbia. It completely altered my way of thinking about literature. I was young and impressionable: a sophomore completely immersed in the reflections on language that come out of Milton. They informed my ideas of the New Babel and triggered the mad theories I ascribe to Henry Dark in City of Glass. At the personal level, City of Glass is also a kind of shadow autobiography or biography. I imagined, in an exaggerated way, what might have happened to me if I hadn’t met Siri (Hustvedt). In some sense, it’s an homage to her. I truly felt she saved my life when I met her.

IBS: Without her you would have been Quinn?

PA: Maybe, maybe. Other crucial sources of inspiration were the wild child stories, which opened on to all the questions about language that have always interested me. I wrote a great deal about these linguistic issues when I was younger. They were integrated into an earlier project that was somehow a combination of Moon Palace and City of Glass—one enormous work, far too big for me to handle. Many of the ideas in City in Glass come out of those embryonic writings, for instance, forming letters with the steps of a person walking through a city and the conversation about Don Quixote with the “Auster” character. It’s a completely mad reading of Don Quixote, by the way, and I have to insist that I was making fun of myself. Almost everything “Auster” says is the opposite of what I believe.

IBS: I can see that [laughs]. He’s also described as an unreliable person and unpleasant.

PA: Well, not so unpleasant . . .

IBS: He “behaved badly throughout.”

PA: Yes, yes [laughs].

IBS: There’s a moment toward the end of The Locked Room where the narrator suddenly injects this somewhat astonishing declaration:

These three stories are finally the same story, but each one represents a different stage in my awareness of what it is about.

Did you plan for them to mirror one another from the beginning?

PA: No. This is how it started: as I was working on City of Glass in 1981, I realized that I’d written something similar about five years earlier in a play entitled Blackouts, and I revisited the play to see if it could be reconfigured as a piece of narrative prose. So, I went back, adapted ideas from the older material and, indeed, Blackouts became the origin of Ghosts. Once I was writing the second volume, I knew there had to be a third. And so, it became a trilogy.

IBS: You say the three novels are different dimensions of the same story.

PA: The issue that runs through all of them is ambiguity. Ambiguity and uncertainty. If I had to boil it down to one phrase, it’s this: “learning to live with ambiguity.” This is the essence of The New York Trilogy. That explains why, at the very end, the narrator of The Locked Room throws away Fanshawe’s manuscript.

IBS: Because it marks yet another dead end for him?

All the words were familiar to me, and yet they seemed to have been put together strangely, as though their final purpose was to cancel each other out. Each sentence erased the sentence before it, each paragraph made the next paragraph impossible.

PA: It’s about uncertainty, and the fact that there are no eternal givens in the world. Somehow, we have to make room for the things we don’t understand. We have to live with obscurity. I’m not talking about a passive, quietistic acceptance of things, but rather the realization that there are things we’re not going to know.

IBS: That’s very interesting, “learning to live with ambiguity.”

PA: Perhaps.

IBS: I suppose it plays into the narrator’s considerations here:

I have been struggling to say goodbye to something for a long time now, and this struggle is all that really matters. The story is not in the words; it’s in the struggle.

I took this struggle to be about writing.

PA: It is about writing, but at the same time it’s about accommodating the unknown.

IBS: Saying goodbye to the absolutes?

PA: I believe so, yes.

IBS: Well, if this book is where some of your major realizations concerning knowledge and truth were consolidated, might we not see The New York Trilogy as one of your most important books, if not the most important? The reviewers and critics do.

PA: I don’t know. I think there’s a tendency among journalists to regard the work that puts you in the public eye for the first time as your best work. Take Lou Reed. He can’t stand “Walk on the Wild Side.” This song is so famous, it followed him around all his life, and he’ll always be best known for having done that. Similarly, no matter how many movies he made afterward, Godard will always be best known for Breathless. It’s true for novelists; it’s true for poets. Even so, I don’t think in terms of “best” or “worst.” Making art isn’t like competing in the Olympics, after all.

IBS: I’m not suggesting The New York Trilogy is your best book but that, generally speaking, it may be your most important work.

PA: Most important in the sense that it’s the most read and most studied of my books, perhaps.

IBS: Why do you think that is?

PA: I don’t know, I don’t know. It seemed to have struck a lot of people as innovative.

IBS: It is innovative. Very much so, and, for one reason or another, what’s new about it concurs with the ideas that emerged in French theory and hit the literary scene round about the time you published The New York Trilogy.

PA: As you know, I was not involved with any of this.

IBS: I know. It’s just a strange coincidence.

PA: I have a feeling that, as the years go by and as French theory diminishes in importance, people will stop reading my books in that way. At least I hope they will.

IBS: Perhaps. Still, I think some of your early work will go down in history as quintessentially postmodern. I know you’re not happy about being placed in this category.

PA: The New York Trilogy is always going to be attached to my name, no matter where I go, no matter how many other things I write. There’s nothing I can do about it.

IBS: Is it necessarily a bad thing? Does it irritate you?

PA: The fact is that I don’t even know if I think The New York Trilogy is very good. To me, it seems rather crude. I think I’ve become a better writer. These are youthful texts that mark the end of a certain phase of my life.

IBS: Even so, you experimented with literary convention, opened new possibilities in fiction, explored ideas. These early books, especially The New York Trilogy, raised very important questions about truth, about language, about being in the world. They prompt reflection about issues that were absolutely pivotal in contemporary literary theory.

PA: I’m not going to pretend they’re not philosophical books.

IBS: More so than The Invention of Solitude, I think, even if it also invites a great deal of reflection.

PA: In the second part of The Invention of Solitude, I explore many of the same questions, but more from a historical perspective than from a purely philosophical one.

IBS: Both The Invention of Solitude and The New York Trilogy have captivated audiences all over the world. My students absolutely love them. I taught them again (probably for the tenth time) last week and after the lecture one of my students came up to me and asked me to give you this letter. It says that your work has changed his life and now he wants to become a writer!

PA: [Laughs] I pity him.

IBS: It has that effect. He was overwhelmed. He could hardly breathe, and he had to stay behind to talk about his experience.

PA: Is he a graduate or undergraduate student?

IBS: Well, they’re in their fourth or fifth year. Just before they finish their MA. I’ve had several students with similar reactions over the years.

PA: Well, I’m happy.

IBS: I think it has to do with your special combination of enchanting storytelling and intellectual challenge: it opens up new ways of thinking about how we try to make sense of the world. It addresses issues we all grapple with, perhaps especially when we’re young. One of the most striking features, not just in your early work, is the fact that your questions only ever open to more questions. Answers are rarely provided. You are so interested in the processes and mechanisms of writing that you lay them bare and weave your thoughts about them into the stories themselves.

PA: I’ve been reflecting on these questions all my life.

IBS: Surely, all writers do that.

PA: Most writers are perfectly satisfied with traditional literary models and happy to produce works they feel are beautiful and true and good. I’ve always wanted to write what to me is beautiful, true, and good, but I’m also interested in inventing new ways to tell stories. I wanted to turn everything inside out. I suppose it’s a tremendously ambitious stance: not to be satisfied with conventions, to play with them sometimes, then to expose traditional norms and stretch them beyond their limits.

IBS: With a view to laying them bare or just to see what happens when you probe?

PA: I want to turn things inside out. Like an architect building a house with all the plumbing and wiring exposed. I’m fascinated by the artificiality of literature. We all know it’s a book: when we open it, we all know that it’s not the real world. It’s something else. It’s an invention. I think that’s why I found it so interesting to put my own name in the first volume of the Trilogy. The name is printed on the cover and then, well, wouldn’t it be curious to have the same name also inside the book—and then see what happens? I was playing with the split between what I call the “writing self ” and the “biographical self.” Here I am, I’m still sitting at the red table with you, I take out the garbage, I pay my taxes, I do everything everybody else does. That’s me. At the same time, there’s the writer who’s living in another world altogether. I somehow wanted to connect those two worlds.

__________________________________

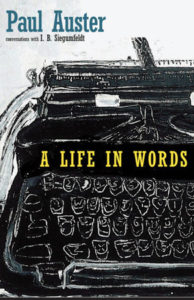

From A Life in Words: Conversations with I. B. Siegumfeldt by Paul Auster and I. B. Siegumfeldt. Used with permission of Seven Stories Press. Copyright © 2017 by Paul Auster and I. B. Siegumfeldt.

Inge Birgitte Siegumfeldt

Inge Birgitte Siegumfeldt is an associate professor of English, Germanic, and Romance Studies at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and the driving force behind the Paul Auster Center that is housed there.