Out of the Shadows: On the Forgotten Mothers of the Occult

Lisa Kröger and Melanie R. Anderson on the Women Behind Ouija and Tarot

Is it possible we are living in the golden age of the occult? After all, the occult is all around us today. Suburban housewives regularly burn sage to cleanse their homes. Gentrified neighborhoods have Starbucks on one corner and crystal shops on the next. Tarot cards are sold in Barnes and Noble.

In the past, the word witch was used as an insult, an accusation. Those who practiced kept their craft undercover, in the protection of covens, keeping any occult practices secretive. Today, if you casually mention a full moon magical ritual to a neighbor, the worst you’ll probably face is a funny look—and you might even make a friend.

But who led us down that path to occult acceptance? How did we get from the Salem witch trials, when any association with the occult could mean a death sentence, to a book like this one, examining women’s history with the occult? The evolution was slow and involved many founding mothers taking small steps along the way. These women were at the forefront of a quiet revolution. Their ideas, their words, and their artistry changed the lenses through which Americans viewed religion and spirituality.

*

HELEN PETERS NOSWORTHY

The Woman Who Built Ouija

If there is one lesson that the horror movie has taught us, it’s that the Ouija board is a doorway to the spiritual realm—and it is something not to be messed with! Movies such as The Exorcist, Ouija, Paranormal Activity, and The Conjuring 2 all feature characters who play with the spirit board, only to be possessed and tormented by demons and evil spirits for the duration of the film. It makes for terrifying and tingling tension, but the board itself has its own fascinating history, with a woman at its center.

The so-called talking board emerged in the midst of the Spiritualist movement of the late nineteenth century, as a useful tool for mediums contacting the other side. Prior to its popularity (and commodification by a toy company), different modes of consulting the spirits were used, from reading tea leaves to holding a pendulum.

Rudimentary talking boards date back to the ancient world, but the talking board we now know as Ouija dates to the late 1800s. The first advertisements proclaimed it to be a link between the spirit world and the material one, providing answers with “marvelous accuracy” and “never-failing amusement.” Visually, the talking board hasn’t changed much from those early versions: they were flat rectangular boards with the words yes and no in the corners and, in the middle, the alphabet and the numbers zero through nine.

Each set came with a teardrop planchette to guide the spirits as they answered questions. The boards marketed in the 1890s were made of wood, including the planchette, whereas today’s versions typically are made from cardboard and plastic. They’ve also increased the price quite a bit; the original boards were advertised with a $1.50 price tag.

It only took a few years for entrepreneurs to begin to market these early boards to be sold directly to consumers for use in their own home. In 1890, the Kennard Novelty Company was formed to fill this niche market. The company designed its own board, complete with letters and numbers to aid the spirits, but it needed a unique brand for its new design.

Nosworthy reportedly sat down with Elijah at the board and asked it what it should be called. The planchette began to move, and slowly, they watched as it spelled out o-u-i-j-a.

Enter medium Helen Peters Nosworthy, the sister-in-law of Elijah Bond, one of the owners of Kennard Novelty Company. Unfortunately, not much is known about Nosworthy. The recorded history of Ouija includes the entire histories of the men who ran the Kennard company (and their dramas while keeping the business going), but not much has been preserved about her. We do know that she was considered a “strong medium,” at least according to her brother-in-law Bond, which is perhaps why she was asked to help come up with a marketable name for this new talking board game. It was her idea to ask the board itself what it wanted to be named.

Nosworthy reportedly sat down with Elijah at the board and asked it what it should be called. The planchette began to move, and slowly, they watched as it spelled out o-u-i-j-a. When they asked for clarification on what this meant, the board simply spelled out good luck. (People often say that the Ouija name comes for the French and German words for yes, oui and ja, but the Kennard Novelty Company has never said this.)

To add to the lore surrounding the mysterious name, the owners of the Kennard Novelty Company said that the Ouija name was confirmed because Nosworthy was wearing a locket that day with a woman’s picture and the name ouija printed inside. Most scholars think that Nosworthy’s locket most likely contained a picture of the writer (and women’s rights activist) Ouida, but that wouldn’t be quite as eerie as the original story.

The Ouija board was a moneymaker for the Kennard Novelty Company, so much so that by 1892, the company expanded from its one factory in Baltimore to two factories. Then they added two more in New York City. The expansion continued so rapidly that year that three more factories were added: two in Chicago and one in London. The Ouija board was officially international.

The Ouija board continued to find success and transform into something of a cultural phenomenon. In May 1920, the Saturday Evening Post included a cover from Norman Rockwell, one of the best-known painters of American culture at the time, depicting a man and a woman consulting a Ouija board.

Today, Helen Peters Nosworthy is considered the mother of the Ouija board. In 2018, the Talking Board Historical Society paid tribute to her with a monument at Fairmont Cemetery in Denver, Colorado, where Ouija fans and history buffs can visit her gravesite. At the ceremony following the unveiling of her monument, a Ouija board was raffled off—a fitting tribute to the woman who named the famous board.

*

PAMELA COLEMAN SMITH

The Mother of Tarot

Perhaps because it’s so accessible—it’s inexpensive and comes with easy instructions—tarot card reading is an especially popular form of occult dabbling. The internet has made a wide marketplace for all kinds of tarot, offering everything from unicorn-themed decks to illustrator Lisa Sterle’s Modern Witch Tarot deck (whose cards feature drawings of women in modern dress) to Labyrinth decks for the David Bowie enthusiast. No matter what stokes your intuition, chances are there’s a deck designed especially for you. Still, most consider the definitive tarot to be the Rider-Waite deck, so named for the famed mystic A. E. Waite and the publisher William Rider and Son.

Based on a long history of illustrated playing cards (used both for games and for telling the future), the Rider-Waite deck introduced the Major Arcana and Minor Arcana as we know it today. It is still the most popular deck, and the imagery and symbolism it introduced heavily influence the art of newer decks, even the Labyrinth one. But that imagery didn’t come from the pens of Mr. Rider or Mr. Waite. It’s the work of an extraordinary woman named Pamela Colman Smith.

Smith was the artist responsible for the cards in the Rider-Waite deck. Born to American parents, Smith spent her childhood moving between England, New York, and Jamaica, where she became enamored with the folklore of the island. She may have been biracial (some have suggested that she had Jamaican roots in her ancestry), and she certainly loved Jamaican culture, incorporating it into her art and her clothing style.

Like her ethnicity, her sexuality is a subject of speculation. Plenty of accounts suggest that she was queer and that she preferred relationships with women. We’re uncertain about these details in part, it seems, because Smith wanted it that way. Sexuality and identity were fluid for her. If someone asked whether she was Japanese, for instance, she might respond by creating a portrait of herself dressed in a kimono. As an artist, she seemed keenly aware that people viewed her as an other, and she wanted to explore what that meant.

In light of her obsession with art and folklore, her bohemian lifestyle was a given. She would often host writers and artists in her studio, holding salons to discuss whatever mystical philosophy was the topic of the day. Smith studied art in New York before moving to London, where she worked at the Lyceum Theatre. During her time there, Smith worked with Bram Stoker, author of Dracula (which was performed at the Lyceum as a play). She then teamed up with Stoker as illustrator of his 1911 book The Lair of the White Worm.

Working with writers turned out to be quite special for Smith, especially when she met William Butler Yeats, who was keenly interested in occult subjects (he was part of the Ghost Club that later included Algernon Blackwood, writer of weird fiction, among many others). It was Yeats who introduced Smith to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which she joined in 1901.

Working with writers turned out to be quite special for Smith, especially when she met William Butler Yeats, who was keenly interested in occult subjects.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was a secret society that explored aspects of the occult and the paranormal, as well as philosophy and magic. Members over time included Blackwood, as well as other creatives like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (creator of Sherlock Holmes) and Arthur Machen (a horror novelist best known for his 1890s novella The Great God Pan). Famed occultist Aleister Crowley also took part. In this group Smith met A. E. Waite. Smith followed Waite when he left the group to form his own offshoot, and it was then that he approached her about his idea for a deck of divination cards.

At Waite’s urging, Smith took on the task of both reinventing old images and creating entirely new ones for his deck, including the backs of the cards, for which she received, according to her, “very little cash.”

After completing her work on the deck, Smith faded from the occult scene. She converted to Catholicism, and though she continued to produce art, she had trouble selling pieces the way she used to. She died in London in financial trouble, and even her burial place is not known today. The tarot deck she created took on a name that left her out completely. She was seemingly erased from an enormous part of occult history.

Today, though, that is changing. Many tarot readers refuse to use a Rider-Waite deck out of protest. Others call it the Smith-Waite deck, a subtle reminder of the woman who created their favorite tool. Many shops now carry the traditional deck with her name in bold letters across the cardboard box: “The Rider-Waite deck with illustrations by PAMELA COLMAN SMITH.”

It’s a start. Still, it is more than a bit frustrating that the occult society that seemed to welcome powerful women, women who left other religions, couldn’t make a history or a legacy for one of its founding mothers.

If nothing else, we can say her name now.

____________________________

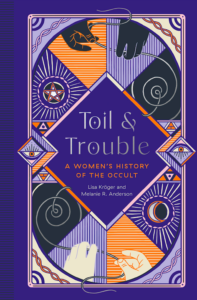

Excerpted from Toil and Trouble: A Women’s History of the Occult by Lisa Kröger and Melanie R. Anderson. Reprinted with permission from Quirk Books.

Lisa Kröger and Melanie R. Anderson

Lisa Kröger holds a PhD in English. Her stort fiction has appeared in Cemetery Dance magazine and Lost Highways: Dark Fictions from the Road (Crystal Lake Publishing, 2018). Melanie R. Anderson is an assistant professor of English at Delta State University in Cleveland, MS. Her book Spectrality in the Novels of Toni Morrison (Tennesee Press, 2013) was a winner of the 2014 South Central MLA Book Prize.