That winter, the year Boogie turned 14, we got it in our heads that we could run away, leave Miami Beach and never come back. For months, I’d spent every night lost in a book, read whatever the librarian put in my hands, which usually meant books written by white men, about white people, for white people. The librarians at the Miami Beach Public Library never, ever, recommended books about black and brown people, about queer girls from the projects, about people like me. I didn’t even know those books existed.

So I read The Virgin Suicides over one weekend. I finished Dracula during three days we were without power because somebody didn’t pay the FPL bill, used a flashlight to light its pages under my covers. I read Stephen King’s It over several weeks and then walked around the neighborhood looking for the opening to the sewers under Miami Beach. Didn’t find it. And then I read The Catcher in the Rye and lost my shit for Holden Caulfield. I decided to do exactly what Holden did. I’d run away from everything. Home, school, everyone. Except Boogie. I’d take her with me.

I’d told Boogie about my plans one night while we smoked my mother’s cigarettes in the park, how I’d been thinking of getting the hell out. We were sitting on a park bench, Boogie watching the boys play basketball, her auburn hair falling down her back in layers, her winged eyeliner making her brown eyes pop.

“Let’s do it,” she said. She was down. She’d seen my life, had spent hours huddled with me in my bottom bunk when I still lived with my mother, had held me while Mami, in the middle of a psychotic episode, ran around talking to herself, opening closets and cupboards and bedroom doors looking for a man she said had followed her home and was hiding in our apartment. Boogie had sat with me on my bedroom floor, her arms around my neck, after my mother came after me with a knife, had helped the men pull me out of the water when I jumped into Biscayne Bay and almost drowned.

Boogie had her own problems—her mom paid more attention to her man than to her, she was always fighting with her dad—but she was like me. She read books on the down low, dreamed of becoming a famous singer one day, getting the fuck out of Miami and traveling the world. We talked about what our lives would be— we’d get gigs playing jazz clubs around the country. She’d sing, because she could actually sing, and I’d play the piano or the bass and write all the songs. Eventually, when we got older, I’d write books about our time on the road. We dreamed up adventures, hitchhiking to New York City, although I wasn’t looking for a specific place, since I didn’t believe there was any place I belonged.

We wanted to meet exotic characters at subway stations, hang out at the Lavender Room, ice-skate in Central Park. We’d be just like Holden, except we’d take advantage of our time in the city and have sex. Lots of it. We’d find some New York rappers in baggy jeans and basketball jerseys and we’d have sex in the back of their limo while listening to Mobb Deep’s “Shook Ones” or Wu-Tang’s “C.R.E.A.M.” We’d party at the Limelight, become club kids, wear Halloween costumes in February. Pink hair, silver glitter eye shadow, blue lipstick, leather dog collars. Noses, eyebrows, lips pierced. I’d be nothing like the ordinary girl who lived with her crazy mother across the street from Normandy Park, the girl who was full of secrets, who believed in monsters. I would finally be free.

That winter, when the Christmas lights went up around Normandy Isle and South Beach, when all the Miami radio stations started playing “Feliz Navidad,” Boogie and I took off. I didn’t leave a note, didn’t give any explanation, and neither did Boogie. There would be nothing left for our parents when they discovered that we were gone. We figured it’d be easier that way, that nobody would try to find us, or worse, stop us.

*

I tossed a change of clothes into my JanSport and we hit the street, walking along Normandy Drive, and I stuck my thumb out once we got to the corner of 71st and Collins.

“We can’t just get into some random dude’s car,” Boogie said. “We need to be smart.”

“Okay,” I said, but when a green sedan pulled over, we climbed in without even a second glance at the driver.

His name was Carlos, and he was headed toward Bird Road. We had no idea where Bird Road was, but we took the ride anyway.

He was a middle-aged man with a thick mane of black hair that screamed “Just For Men.” I rode shotgun while Carlos drove us down the 836, a lit cigarette pinched between his lips. He asked questions about our boyfriends and our parents, and what exactly two 14-year-olds were doing getting in cars with strangers. “We ran away,” I said, checking myself out in the visor mirror.

“Why’s that?” he asked.

I shrugged. “Because home sucks. Because this whole fucking place sucks.”

“You shouldn’t talk that way,” he said, “a pretty girl like you.”

But I wasn’t falling for his bullshit. From my mother, I’d learned that men always pretended to give a shit about you, saying exactly what you wanted to hear when there was something they wanted. And men always wanted something.

I reached into the center console for his Marlboros, plucked one out for myself, tossed the pack to Boogie. As he pulled off the road and we approached the sign for Santa’s Enchanted Forest—Miami’s Christmas theme park—I got an idea. Boogie and I had never been there, so it seemed like destiny: it was exactly where we were supposed to be.

I snuck a look at Boogie over my shoulder, gathering my curls into a ponytail. I smiled at Carlos like I’d never smiled at any man before, and asked him if he would take us to Santa’s Enchanted Forest.

I knew there would come a moment when the night would end, when Carlos would show us what he really wanted.“I can drop you off out front,” he said. But he hadn’t caught my meaning. I hadn’t meant for him to drop us off, since we barely had three dollars between the two of us and couldn’t pay the entry fee, whatever it was. Then there were the rides, the food, the arcade.

“No,” I said. “I mean take us take us.”

We stopped at a red light, Carlos looking over the steering wheel without a word. I let go of my hair, my curls falling over my shoulders. Boogie sat in the back, eyebrows raised, waiting.

“Fine,” he said. “Let’s go.”

I threw my hands up over my head, and Boogie hooted. Carlos smiled, adjusting himself in the driver’s seat, tossing his cigarette out the window. And then the light changed.

Inside Santa’s Enchanted Forest we caused all kinds of hell. We made Carlos pay the entry fees, treat us to ice cream, elephant ears, pizza. We cut in line, left him behind while we rode the Gravitron and the bumper cars. We got on every ride while he pretended he was some sort of throwback hustler, wearing his shades after the sun set, chain-smoking, bobbing his head to whatever music the DJ played. I never wondered why he took us, why he was paying for everything, never even considered the reason he’d spent all night waiting on two underage girls he picked up on the side of the road, because I knew—I knew, even if Boogie didn’t, that there would come a moment when the night would end, when Carlos would show us what he really wanted, and what he really was.

*

After hours in Santa’s Enchanted Forest, after we got tired of every other ride, Boogie and I rode the Ferris wheel, sucking on the Ring Pops Carlos had bought for us. We rode side by side, and as our car rose, we took in the whole park: the cast members dressed as Santa’s elves and a carrot-nosed Frosty the Snowman, the fake cotton snow under the Christmas trees lining the main strip, kids finishing up their corn dogs and cotton candy as they boarded the carousel, everywhere the smell of cinnamon and fried dough, teenagers lining up for the Space Coaster and the MegaDrop. And then, when we got to the top, there it was: the tallest Christmas tree in South Florida.

Later, Carlos would change. He’d get mad at us for flirting with a group of boys from Treasure Island, and when Boogie kissed one of them outside Santa’s Grotto. He’d corner me by the workshop assembly line, squeeze my breasts hard. I’d push him back, but it would do no good because he was stronger than me and his eyes were already glazed over with too much beer and too much desire. He’d reach down and grab me there, between my legs. And then he’d give me a look that only I could read, a look that said I owed him, this was the price for my wildness and my freedom, I was his. But then Boogie and the boys would show up and Carlos would let go, and I’d think, Thank you thank you thank you oh my God, grab Boogie and make a run for it, ditch Carlos and ditch the boys, too. We’d take the last bus back home, ride up front while the driver listened to the Jesus station, and years later I’d remember this moment and think about Holden, how he ran after Mr. Antolini tried to hit on him, how the whole book was about Holden running, but he didn’t really go anywhere but home, because maybe in the end he had nowhere else to go.

But all that would come later. While we were still on that Ferris wheel, still in that moment on top of the world, Boogie and I had no idea. We just sucked on our Ring Pops and looked out at the theme park, at the people and the lights and the fake snow and the tacky-ass Christmas stuff, even though we were less than an hour away from Miami Beach, and in that instant, we let ourselves believe that we were on our way, or that we had somehow already made it. That we were already free.

*

The spring China turned 15, we were herded into a banquet hall for her quinces, all of us in our magenta ball gowns, elbow-length gloves, hair pinned up in elaborate twists, lips painted red. We walked down the aisle, our dance partners in their black tuxedoes, magenta bowties to match our skirts. As “Tiempo de Vals” blared from the speakers, we swayed to the music like we were in some old movie, counting one two three four, one two three four in our heads with the rhythm of the music, just like China’s tía had taught us, the boys’ hands at our waists, our palms sweaty in our tacky-ass gloves. We winked at each other from across the room, stuck our tongues out when we caught China’s eye, giggling while her family watched from their extravagantly decorated tables. We twirled and twirled in our wide skirts, and when the song finished, we kept dancing, another song and another and another, all of us smiling and sweaty and breathless, overcome with too much Keith Sweat and Boyz II Men, too much “Freak Me” and “Rub You the Right Way.” We stopped caring about how anybody saw us, what they might think.

We would talk about how they were so young. We knew nothing but what eyes could see.After the boys had left the dance floor, after the pictures and the cutting of the cake, after all of us changed out of our magenta ball gowns and into little black dresses we’d picked out for ourselves, after we let our hair down and kicked off those ridiculous heels, we went back out on the dance floor, just the girls, hanging on to each other. We sang along to every song, our cheeks flushed, our curls sticking to our foreheads, the backs of our necks, our shoulders and backs glistening, and we stopped thinking about the real world, our real-world problems, who was on house arrest, whose brother had just gotten a ten-year sentence for racketeering, whose parents were living paycheck to paycheck. We felt the music vibrating through our bodies, fingers to toes, the beats hammering on our chests, filling us. We were beaming. We were breath and rhythm, laughing and laughing in each other’s arms, and for a while, as the world was spinning, blue and red and yellow lights flashing all across the banquet hall, I looked around at us, at my girls, round faces covered in their mothers’ makeup, how we would all be in high school in a few short months, and all I could see was how much I loved them, how much I loved us.

I didn’t know it yet, none of us did, but it would be these hood girls, these ordinary girls, who would save me.

*

The fall after China’s quinces, the year we started high school, Shorty and I became friends. We’d known each other before, met when some friends and I were planning to fight some other Nautilus girls—a ridiculous one-minute roll on the sidewalk that ended with one of the girls having a seizure in front of Hunan Chinese Restaurant, the rest of us scrambling in ten different directions when the cop cars pulled up, lights flashing.

Shorty turned out to be one of my closest friends, even though we hadn’t known each other long—she’d moved down from Chicago just a year before. We fell into an easy friendship, growing our hair long, dressing alike. She was small, with doe eyes and a dash of freckles across her nose, and she was always, always, smiling. That fall, that year, she was one of the few people I went to with my fears, my dreams, my anger.

In our first period music class, Advanced Chorus, we got split into separate sections, Shorty with the sopranos, and me with the altos. Every morning we’d walk in, sit together, talk shit about some of the other alto girls, the girlfriend of some dude Shorty had a crush on, the sister of a boy who’d snitched on me while I was skipping. Until Dr. Martin walked in and sent me on my way, back to the altos. From my spot on the second row, I watched Shorty, standing directly across from me in the semi-circle, smiling, her eyes wide. It killed me that I wasn’t a soprano, that I couldn’t reach those high-ass notes like Shorty. But also, that I couldn’t sing next to her, that we never got to be side-by-side as we tried to sound like Alvin and the Chipmunks singing Billy Joel’s “You May Be Right,” or when we changed the lyrics to Boyz II Men’s “End of the Road” to something nasty, or when we danced and clapped like a gospel choir while we sang “Oh Happy Day.” I was secretly obsessed with Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit, and crushing hard on Lauryn Hill, so I didn’t even mind singing about Jesus.

That winter, we watched New York Undercover on group phone calls, Boogie and China and Flaca and Shorty and me, all of us on the party line, screaming at the TV when Malik Yoba, Michael DeLorenzo, and Lauren Vélez took off down the street chasing some drug dealer. We cut pictures of Jodeci and Boyz II Men and 2Pac from magazines, taped them on the covers of our notebooks. We watched Janet and Pac fall in love in Poetic Justice, and we all wanted to be Janet, scribbling poems on the margins of our textbooks, strutting into school in baggy jeans and combat boots. We watched The X-Files, imagined ourselves solving paranormal mysteries, having alien babies, turning into monsters. And then we speculated about the size of Mulder’s dick. We felt the warmth of that place between our legs and there was nothing monstrous or strange about it.

That winter, we measured out our life in songs, singing as we put on eyeliner in front of the mirror, as we passed each other in the halls at school, as we waited for the bus across from the park. We belted out Mariah’s version of “I’ll Be There” in China’s mother’s car on the way to a sleepover. We broke into fits of spontaneous booty shaking as we walked along West Avenue, when a car drove by blasting “Shake Whatcha Mama Gave Ya,” as we rode the escalator in Aventura Mall. We choreographed dances to “Pop that Pussy” and “The Uncle Al Song” at China’s house. We knew all the lyrics to every single DJ Uncle Al song—“Mix it Up,” and “Hoes-N-Da-House,” and “Bass Is Gonna Blow Your Mind.” Uncle Al, who was known all over Miami for promoting nonviolence and peace in the hood, but was shot and killed outside his house in Allapattah. We dogged each other to “It’s Your Birthday” while hanging from the monkey bars, lightning in our limbs, while drinking orange sodas at Miami Subs, while tagging the handball courts. Everywhere Boogie, China, Flaca, Shorty, Jaqui.

That spring, we paid tecatos at 7-Eleven to get us bottles of strawberry Cisco, took the bus to Bayside, got on the party boats, danced and danced and danced with older boys, handed them our phone numbers at the end of the night. We rode to the all-ages clubs, Pac Jam and Sugar Hill and Bootleggers, where they sold no alcohol but everybody smoked weed. We passed the blunt across the dance floor, all of us sweaty and smiling, and onstage, older girls dusted with baby powder shook and shook their asses, flashing us their tits, all the girls booing, all the boys screaming, cheering, fists in the air. We smiled at each other nervously, recognizing some of the girls we knew from school, two years ahead of us, three years ahead of us, our friends’ cousin, a girl my brother dated once. And one day that winter, we would hear about one of those girls—see her face on the news—about how she and her best friend were found floating in Biscayne Bay, strangled, tied together. Their school pictures all over our TVs for days, for weeks, their story on the front page of the Sun-Sentinel with the headline “They Were Inseparable Friends—And They Were Slain Together.” We would remember their dancing, speculate about the who, the how, the why. We would talk about how they were so young, had so much life left to live, as if we knew anything about life and living it. We knew nothing but what eyes could see.

That summer, on the last day of school, me and Shorty cut out after lunch, headed to the beach for National Skip Day, the two of us in Daisy Dukes and chancletas, our curly hair wild and frizzy and sun-streaked. At the South Pointe pier, high school kids in bathing suits and shades, seeing each other’s bodies for the first time, blasting Bone Thugs-n-Harmony’s “Thuggish Ruggish Bone” on their radios, catcalling girls across the way. Then, when a fight broke out, one dude holding the other underwater, arms swinging wildly, we ran toward the shore to see it. When he was finally able to get free, none of us saw it coming: the walk back to his car, the loaded gun pulled from his glove box. How we lost each other in the madness, Shorty running down the shoreline, and me, heading for the water. The bodies on the sand, all of us scrambling away from the gunfire. Later that night, we would watch ourselves on the news, all those teenagers loose on the beach, on the pier, no parents anywhere, the faraway spray of whitecaps breaking.

Just weeks later, me and Shorty were back on the beach, knocking back Olde E with some dudes we’d just met. The sun on our faces, bikinis under oversized T-shirts, we walked a couple blocks to their place. And once we were there, 15 and 16 and in a stranger’s apartment, DJ Playero’s “Underground” on the radio, it was so clear, so easy to see. How they separated us, knew exactly what to say. Shorty in the bathroom, me in the living room, the bottle half-empty on the floor. How I never thought to ask how old he was—old enough to buy alcohol, to have his own apartment. How he ripped my bathing suit, the banging on the bathroom door, his hand over my mouth, the music so loud. How I pushed back, kicking, reaching for the ashtray, the remote, anything, until finally, the bottle, and I was Shorty and Shorty was me and we were every girl, we had not been alone, all of us in that apartment, in that bathroom, all of us breathing, alive, lightning in our limbs, banging on that door for minutes, hours, a lifetime, and for a moment I thought it was possible that I could lose her, that I could be one of those girls.

It was the same the next summer, and the summer after that: we went right back to drinking, smoking, fighting, dancing dancing dancing, running away. We wanted to be seen, finally, to exist in the lives we’d mapped out for ourselves. We wanted more than noise—we wanted everything. We were ordinary girls, but we would’ve given anything to be monsters. We weren’t creatures or aliens or women in disguise, but girls. We were girls.

———————————————

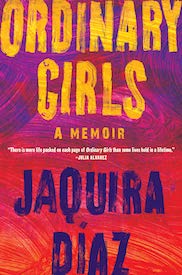

From Ordinary Girls: A Memoir by Jaquira Díaz. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2019 by Jaquira Díaz.