Open to Interpretation: The Brief Relationship of Susan Sontag and Jasper Johns

On the Highs and Lows of Art and Life

In early 1965, Susan Sontag began a relationship with Jasper Johns. Like many of the men she had affairs with, Johns was mostly gay; and as with most of the men Susan was involved with, the relationship was brief. And—as with all the men she was involved with—Johns was supremely talented: “My intellectual and sexual feelings have always been incestuous,” she said.

Johns’s philosophical preoccupations harmonized perfectly with her own—and, at least at first glance, with Warhol’s. Johns and Warhol were born to obscure provincial families within two years of each other. Both “arrived” on the New York art scene in the 1950s, and both stood firmly in the tradition of Marcel Duchamp, who had plucked objects from the rubbish and placed them in the museum. Warhol painted tins of Campbell’s soup and bottles of Coca-Cola; Johns, Savarin coffee and Ballantine ale.

But where Warhol refused interpretation—for him, a picture of Elizabeth Taylor was exactly that—Johns masked the “real” meanings of his paintings, which refused interpretation not because, as with Warhol, they had no hidden meanings, but because their creator refused to reveal them. “I tried to hide my personality, my psychological state, my emotions,” he said of his early work. “Playfulness with masks” was the key to Susan’s own work, too.

Painted in 1954, Flag came to him in a dream. “I have not dreamed of any other paintings. I must be grateful for such a dream!” he exclaimed in an explanation redolent of Hippolyte. “The unconscious thought was accepted by my consciousness gratefully.” Seen up close, the apparently straightforward image dissolves, and all one can see behind the paint are newspaper clippings. The attentive viewer will try, and fail, to piece them together, as one might try to connect the mysterious objects in a Joseph Cornell box. The only entirely comprehensible symbol is the flag itself, one whose clichéd familiarity let Johns focus exclusively on painting it, forcing the viewer to try—and fail—to discover some other meaning beyond the obvious symbol. “It remained the most interesting point about Johns,” the critic Leo Steinberg wrote, “that he managed somehow to discover uninteresting subjects.” For Susan, this uninterestingness was a virtue, implying a refusal of the easy accessibility she associated with commercial entertainment.

Most of the interesting art of our time is boring. Jasper Johns is boring. Beckett is boring, Robbe-Grillet is boring. Etc. Etc. Maybe art has to be boring, now. (Which obviously doesn’t mean that boring art is necessarily good—obviously.) We should not expect art to entertain or divert any more. At least, not high art.

Flag’s uninterestingness and illegibility made it irresistible to critics, who plastered it with the very interpretations it deliberately thwarted. They posed a classic question—a classical question, indeed: derived from Plato—that animated much of the art of the day: Was Flag a flag, or was it simply the image of a flag? Johns answered that it was both. With that, he addressed a question that had preoccupied philosophers for centuries: Could a thing be both itself and a symbol of itself?

In later years, he would paint objects whose contents were deliberately obscured—books that could not be opened, newspapers that could not be read, canvases with their backs turned toward the viewer—all hinting at some unknowable meaning. In lieu of that content, viewers projected their own interpretations onto them, which could be neither confirmed nor denied. In this case as in so many others, the questions (Can language and metaphor be transcended?) were far richer than the answers (So that’s what’s on the second page of that newspaper!).

But the answers meant a possibility of making art that might overcome the divisions postulated by the gnostics. Such art, as in the performance Susan witnessed of Medea, could dissolve the boundary between art and life, mind and body, image of self and self.

*

In the 1950s, when he was producing these works, Johns’s lover was Robert Rauschenberg, who made his name with vast “empty” paintings. One was all black, another all white. John Cage, who, with his partner, Merce Cunningham, completed this circle of young artists, responded to them with his famous piece of 1952, 4’33”—four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence. He described Rauschenberg’s monochromes as “’landing strips’ for dust motes, light and shadow.” But dust motes, light and shadow, were not the only things that could land on such tabulae rasae. Interpretations, too, could be cast upon their apparently closed surfaces. And Johns appreciated Susan’s.

In Johns, Susan found the same characteristic that she often appreciated in men: he was a master—a teacher.

“I don’t think I could have easily connected my feelings about my work to the Supremes,” Johns said. “Her ability to make such connections was very attractive.” In her journal, she wrote that the “Feeling (sensation) of a Jasper Johns painting or object might be like that of The Supremes.” A version of this line appeared in her essay “One Culture and the New Sensibility”:

If art is understood as a form of discipline of the feelings and a programming of sensations, then the feeling (or sensation) given off by a Rauschenberg painting might be like that of a song by the Supremes. The brio and elegance of Budd Boetticher’s The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond or the singing style of Dionne Warwick can be appreciated as a complex and pleasurable event. They are experienced without condescension.

This dry passage set off disproportional reactions. “The lady swings,” Benjamin DeMott exclaimed, with mingled admiration and mockery, in The New York Times Book Review. “She digs the Supremes and is savvy about Camp. She catches the major Happenings and the best of the kinky flicks.” The mention of the Supremes would be wielded against her for decades, as an illustration of her enmity toward high culture (“The Supremes, for Christ’s sake?” gasped Norman Podhoretz) and as an illustration of a supposed hipness she later abandoned. Twenty-seven years later, her friend Larry McMurtry defended her against an attack:

She occasionally says that she likes rock music, and it’s also true that in “One Culture and the New Sensibility,” an essay published in 1965, she speaks appreciatively of Dionne Warwick and the Supremes, but does this constitute an “interest” that she can be said to have “dropped,” if indeed she’s dropped it? Perhaps she still likes the Supremes.

If Johns was attracted to Susan’s ability to make these connections, they rubbed many people the wrong way. What later became known as Cultural Studies was then in its infancy, and examinations of the difficult relationship between commercial art and high art were often seen as “leveling.” But between the Warhol idea of no interpretation and the Johns idea of no possible interpretation, Susan Sontag would soon come up with an even more attractive idea: of being against interpretation.

*

In Johns, Susan found the same characteristic that she often appreciated in men: he was a master—a teacher, like Hutchins at Chicago, who could give her the “right way.” Stephen Koch said that

Jasper is as dominating, as egotistic, as ready to assume that anyone around him is going to take a secondary position, as the most besotted heterosexual alpha male who ever lived. So it’s not like she found in Jasper the sensitive man that would let her flourish as the dominating personality. That wasn’t it at all. She was very aware that Jasper never conceded anything but first place. That turned her on.

Susan’s desire to submit to superior influences was surely more important than whatever erotic dynamic bound them. Because Johns was a man, Susan could be in his thrall intellectually and artistically while remaining emotionally insulated. Her journals record none of the hand-wringing that makes it so agonizing to read about her relationships with women. When Jasper dumped her, he did so in a way that would have devastated almost anyone. He invited her to a New Year’s Eve party and then left, without a word, with another woman. The incident goes unmentioned in her journals.

The brief relationship had a practical legacy. He left her the lease on his penthouse at 340 Riverside Drive, on the corner of 106th Street. All bright sunlight, wide terraces, and broad views, it would have been entirely unaffordable for a later generation of writers with Sontag’s income; but in the scruffy city of those years, the rent was reasonable, and when Johns moved out, Susan moved in. There was just one drawback. Johns had created elaborate preliminary sketches for his paintings directly on the walls. The apartment was littered with these drawings, and the new tenant had to decide what to do with them. Choosing the simplest option, she had them painted over.

________________________________________

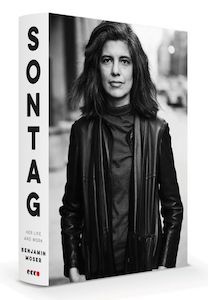

From the book Sontag by Benjamin Moser. Copyright © 2019 by Benjamin Moser. Published on September 17, 2019 by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Benjamin Moser

Benjamin Moser is the author of The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters, published in October 2023 by Liveright.