One Legend to Another: When Jackie Robinson Testifed Against Paul Robeson in Congress

Howard Bryant on Black Leadership and Interracial Heroism

During the Cold War

December 1949, ten days before Christmas. Jackie Robinson, the most famous ballplayer in America, is home—the first Christmas on his new street in his new house in St. Albans, a quiet, integrated neighborhood in Queens boxed in by Jamaica to the east, Long Island to the west, and Idlewild Airport, New York’s new, year-old airport to the south.

It is a festive time, houses adorned with Christmas lights, solo candles flickering from front windows. Ten days before Thanksgiving, Robinson’s son, Jackie Jr., celebrated his third birthday. Over cake and ice cream, the family enjoyed another milestone: Robinson had just won the biggest accolade of his career: the National League Most Valuable Player award. His wife, Rachel, is pregnant with their second child. Robinson tells the newspapermen he hopes it will be a girl.

Three days a week, on Mondays, Wednesday, and Fridays, Robinson works the floor as a salesman at Sunset Appliance Store in Rego Park, not far from his house. At the time, ballplayers, even the best ones like Robinson, work second jobs during the offseason—but for Brooklyn fans, his celebrity is its own gift, a major coup for the store, and further cements him as a Brooklyn hero, not some distant superstar who leaves town after the final out of the season, but one who stays, one of them. Customers who purchase an RCA Victor television from Robinson received an autographed big-league issue bat or ball, and can arrange to have their photo taken with him on the days he is in the store.

The presence of Robinson and his Black teammates no longer felt unique, as it once did, but ubiquitous.

Even The New Yorker, the city’s magazine for the wine and cheese crowd, ventures out to Brooklyn to pay a visit to New York’s most recognizable salesman. It is a precious snatch of time. In a little over a month, before his thirty-first birthday, Robinson will hand out cigars in Harlem, celebrating the birth of his daughter, Sharon.

The home in St. Albans—a two-story, single-family Colonial with a spacious backyard on a quarter-acre lot at 112-40 177th Street—stands as a testament to the possibilities this country believes it offers all people, the possibilities for better, despite the unforgiving realities of Black life. Within this moment, coated in the sugary haze of professional success, a new home, a beautiful wife, and a growing young family warmed by the comforting glow of Christmas-time, Jackie Robinson has never been more ascendant, more complete, more American.

Most veteran baseball men could not envision his success—or did not want to, anticipating it would eventually destroy segregation. Robinson’s excellence justified the fear. During the 1949 pennant race, as the leaves began to change and the Dodgers charged toward the World Series, a Black newspaper columnist noted that in photographs, in print, and in interactions among the other Dodgers, America looked different than it had just two years ago. The presence of Robinson and his Black teammates no longer felt unique, as it once did, but ubiquitous. Perhaps even normal. Robinson was now not only voted the best player in the league but with him the franchise had never been better. The Robinson Dodgers had won the National League pennant twice in his first three years. Before him, Brooklyn finished first three times over the previous fifty.

The accolades and pennants proved he was a great player, but by lunchtime on the afternoon of July 18, 1949, after he had left Room 226 of the Old House building on Capitol Hill following his testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Jackie Robinson had become more than a baseball player. He had testified to the committee against the political opinions of the great bass-baritone singer and actor Paul Robeson, who was more than twenty years Robinson’s senior, himself once beloved by millions of Americans, himself like Robinson once a great football player, once, like Robinson, one of greatest athletes in the nation—and once, as Jackie Robinson was now, the most famous Black man in his country.

America in the summer of 1949 was consumed by fear, convinced it was culturally and politically being infiltrated by agents of the Soviet Union. The fears were stoked by the nation’s highest political and thought leaders—Harry Truman, the Democratic president; Col. Robert McCormick and William Randolph Hearst, two leading newspaper titans; and a desperate Republican Party that had been out of the White House for nearly two decades. The GOP had been out of power for so long it believed its attack on universities, FDR and his New Deal of social initiatives—unemployment benefits, Social Security, and a host of programs future generations of Americans now take for granted as foundational—could no longer be fought along the dry, pasty lanes of policy, but through the mud of accusation: the New Deal was communist, its supporters anti-American, cooperation with the Soviets treasonous.

The excavation of Paul Robeson complicates Robinson and Rickey and destroys, almost completely, the easy, uncomplicated tale of interracial heroism Americans have long preferred.

Who was loyal? No area of American life went untouched by the specter of conflict with the Soviets. Reminiscent of the violence against labor unions, liberalism, and Black soldiers that followed World War I, Robinson testified against Robeson in a climate that was now being called the second Red Scare. Amid these silhouettes of fear, Jackie Robinson was seen as one of America’s champions.

As Christmas neared, Robinson appeared at the Commodore Hotel in New York, accepting the George Washington Carver Institute’s gold medal for improving race relations, a “glowing example of American-ism at its best.” Frank Gannett, the founder of the Gannett newspaper chain, addressed the overflowing audience. “Isn’t it a story to thrill every American?” he said. “Jackie Robinson stands out as proof that here in America there is opportunity for those Black or white, who have ability, determination, character and ambition he is not only a great citizen, but a great American. Rather recently, he appeared before a Congressional committee and defended his race’s loyalty and rejected for them any sympathy for Communism.”

In the August 1897 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, the legendary scholar W.E.B. Du Bois wondered if it was possible for Black people to successfully balance the “double consciousness” of being subjected to a segregated society and still feel “American.” In his essay “The Strivings of the Negro,” Du Bois saw this inner conflict as the defining characteristic of the post-slavery Black experience.

As loyalty and conformity often disguised as anticommunism suppressed the fervency for civil rights that punctuated the war years, Du Bois’s conflict increased in intensity for a Black America expecting an improved quality of life in peacetime. “This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals,” Du Bois wrote, “has wrought sad havoc.”

The years 1945 to 1953, when America transitioned from the Great Depression and the politics of World War II into a cold war with the Soviet Union, shaped both domestic and foreign policy. But overshadowed by the explosive years that would follow, this critical period has largely been treated as dormant Black history. Historians have tended to view the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, and Rosa Parks’s subsequent defiance of segregation as the springboards to the modern civil rights movement—yet these in-between years had a profound effect on Black America.

Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson were central to this overlooked period. Both men served as a prologue of sorts. For the remainder of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st, they were the early prototypes of a new template—the prominent Black entertainer as national political spokesperson. In the 19th century, the voices of Black leadership were the abolitionists and educators, orators, and clergy.

Today, the entertainers, actors, and professional athletes enter the political maelstrom and illustrate Du Bois’s notion of double consciousness, performing for white mainstream audiences while being expected to both advocate for Black issues politically and represent America at home and abroad, a conflict perfected during the Cold War. No race of people have been so politically overmatched. Malcolm X would refer to them as “puppets.”

Through countless published biographies over several decades, Robinson’s 1949 testimony against Robeson on Capitol Hill had long sat in plain sight, explored in only a page or two but usually by a single sentence—Jackie Robinson testified against Paul Robeson—an exposed root on the beaten path of the story of baseball integration.

Why was the exposed root so easily stepped over? Robinson and Robeson were, along with Joe Louis, Jack Johnson, and Jesse Owens, two of the five greatest Black athletes over the first half of the 20th century.

The exposed root sat unbothered, to be stepped over and never tripped upon. As a professional who had traveled that road in short-, medium-, and long-form journalism for decades, how many times had I stepped over it, muscle memory reminding me to lift one foot over the other without questioning what it was, why it was there, and what it might lead to? And how many times had I read the Jackie Robinson story and realized the entire narrative was constructed through the perspective of one man: Branch Rickey?

Why was the exposed root so easily stepped over? Robinson and Robeson were, along with Joe Louis, Jack Johnson, and Jesse Owens, two of the five greatest Black athletes over the first half of the 20th century. Add to Robeson’s resume a law degree from Columbia, an international concert singer, a groundbreaking stage and screen actor, and he was nothing less than a titan. The root needed pulling.

The answers to the questions were not profound. The lens of the hearing never focused on Robeson, who was seen as only a prop for Robinson’s patriotism, unworthy of rediscovery, especially as the Robinson/Rickey integration story—sports as the pathway to equality—became virtually unchallengeable. The excavation of Paul Robeson complicates Robinson and Rickey and destroys, almost completely, the easy, uncomplicated tale of interracial heroism Americans have long preferred.

It was about a decade or so ago when researching another book about the history of the political voice of the Black athlete when I finally stopped, looked down, and inspected the root. By the time I reached my own adolescence in the 1980s, the domestic elements of the Cold War focused on nuclear annihilation, the USA versus the USSR in the Olympics, “Fallout Shelter” signs in government buildings, The Day After.

The years when the federal government turned on its own citizens, corporations fired employees accused of subversion, and neighbors spied on neighbors had long since ended. For my generation, that type of hysteria where no one could be quite trusted to be what they seemed could only be found in The Twilight Zone reruns—until the 9/11 terrorist attacks reignited suspicions.

In our house, Paul Robeson was a disembodied figure, a name with-out a story, appropriate for the market-driven 1980s in many ways. With the disappearing of Robeson also came the disappearance of questioning the effect of free-market capitalism on Black communities, a once vibrant question replaced by the celebration of individual wealth. When I attended college in Philadelphia in the mid-1980s, Robeson grew more present, especially on the Temple University campus. He had lived in West Philadelphia and had died there only a decade earlier, and though his name still resonated throughout the Black communities, it did so in regal, broken fragments.

The late Harry Belafonte once referred to Robeson as “one of our kings.” How, then, could a king become so obscure, especially to his own people? His disappearance could not merely be a function of time because he had not been gone that long. Sand does not replace sand so quickly. The rise of hip-hop and the films of Spike Lee in the late 1980s and early 1990s forced a revival of Malcolm X, a reclaiming of him by Black America, wrested from his historical framing by the white mainstream, which during his time did not love him. To a new generation, Malcolm X became timeless, as Ossie Davis eulogized him following his 1965 assassination: “Our shining Black prince.” Paul Robeson has yet to receive such a reappraisal.

With modern terminology, the anti-liberal playbook of the 1950s has returned, once more, by conflating progressive politics with communism.

Prior to the fateful day Jackie Robinson appeared in Room 226 of the old House building, the continuum of Du Bois’s double consciousness wrestled with itself, during World War I when Black leadership made the strategic choice to temper its domestic militance only to have Black soldiers targeted at war’s end; in employing the opposite strategy during World War II, aggressively campaigning for civil rights during the war years only for Black soldiers to be targeted again physically by white vigilantism and economically by their government, which excluded them from the G.I. Bill and the opportunity to join in the postwar prosperity that created the American middle class; to fight segregation and be called communists for it.

Today, the nation is experiencing a similar period of retrenchment. Loyalty oaths have resurfaced. In 1949, across the flag of the San Francisco Examiner read the words “America First” in block letters and the slogan, “An American paper for American people.”

Today, “America First” has been revived with the familiar hostility of its antecedent. In April 2024, the state of Florida announced it would make courses teaching the “evils of communism” a requirement for grades as low as kindergarten. The University of Nebraska relented to the right-wing assault on Black history, forcing its instructors to rename its “Race and Sports” sociology class “Sports and Culture.”

In May 2025, the White House stated that “children will be taught to love America” and will be taught to “be patriots.” With modern terminology, the anti-liberal playbook of the 1950s has returned, once more, by conflating progressive politics with communism. The election of a Black president and a subsequent political movement against police brutality—amplified by the visibility of Black professional athletes—was met with a similar questioning of the loyalty of Black citizens and a merciless legislative assault on their gains, aggressively reestablishing a regressive white nationalist, Christian hierarchy that hasn’t been part of a presidential mandate since the days of Woodrow Wilson, more than a century ago.

Within these pages is the story of a moment in the continuum, when Jackie Robinson and Paul Robeson, seven years apart, embodied Du Bois’s dilemma in Congress, one man appearing in conflicted service to and the other hunted for ferocious critique of a country that would ultimately and decisively wound both. Through their actions and strategies, both men—along with the NAACP, the Black press, and the Black veterans who believed serving their country would finally make them American—would embody the 19th-century words of Du Bois that have encapsulated the expanse of the Black American journey: “One feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

The word American reverberated throughout that evening at the Commodore, and continued at banquets as Robinson crisscrossed the country, the word hero rarely far from his name. The Oregon Daily Journal referred to him as a “clean-cut American Negro athlete” and lauded Robinson for protecting American values, ostensibly in direct opposition to Robeson. Countless newspapers followed.

__________________________________

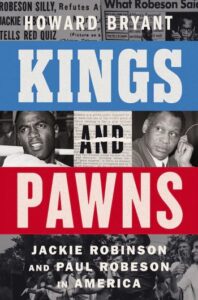

Excerpted from the book Kings and Pawns by Howard Bryant. Copyright © 2026 by Howard Bryant. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Howard Bryant

Howard Bryant is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN the Magazine and has served as the sports correspondent for NPR’s Weekend Edition Saturday since 2006. He is the author of The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron; Juicing the Game: Drugs, Power, and the Fight for the Soul of Major League Baseball; Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston; and the three-book Legends sports series for middle-grade readers. His most recent book is The Heritage: Black Athletes, a Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism. A two-time Casey Award winner (2003, 2011) for best baseball book of the year, Bryant was also a 2003 finalist for the Society for American Baseball Research Seymour Medal. In 2016, he was a finalist for the National Magazine Award and received the 2016 Salute to Excellence Award from the National Association of Black Journalists. He lives in Northampton, Massachusetts.