One Family's Story of the Great Migration North

Bridgett M. Davis Tracks Her Mother's Journey from Nashville to Detroit

By the time my mother was born on May 9th, 1928 (known as Christian Feast Day, which I find fitting), it was two months after Virginia became the first state to pass an antilynching law, something the US Congress never did. She was 17 months old when the stock market crashed in 1929. But based on the stories handed down, there’s no indication that her father lost work during those years. The 1930 census lists my grandfather as a 44-year-old man (he was actually 45) who can read and write, has a wife and seven children still living at home, and is by profession a “plasterer” for the city. The value of his home is listed as $2,000. You have to wonder how its value was determined. Regardless, by then, my grandfather owned five properties.

When she was a girl of just two or three, growing up in Nashville, my mother had such long, sandy-red hair that a doctor told my grandmother it was sapping the child’s energy; and so her mother cut it all off. Left behind were short ringlets that covered her head, causing people to mistake her for a boy.

From that day forward, they say, Fannie Mae’s energy was boundless; I like to think that she was left alone until her hair grew back, to have the freedom usually afforded boys to explore, and today dream. In any event, something instilled in her a desire for more. As she grew, she became a voracious learner, an avid reader and a lover of history. She was smart and honest, so people were drawn to her. Often folks came to Fannie for advice, ideas, tips, and ways to help them out of precarious situations. She just seemed to know things.

She was already honing what would become her twin passions: helping others to improve their station in life, and figuring out ways to improve her own. This combination of charisma, generosity, and drive distinguished my mother from her siblings. Other qualities distinguished her: she loved books, liked expanding her vocabulary, was the prettiest of the Drumwright girls, had impeccable taste, and dressed stylishly. My most treasured photograph captures her at eighteen, in her prom dress, an elegant, scooped-neck frock trimmed in crinoline that shows off her tiny waist and womanly cleavage. She wears a jeweled bracelet with a delicate handkerchief attached to it, and gloves that travel from her wrists to above her elbows. She looks into the camera with dark intelligent eyes.

She also loved beautiful things, and seems to have embraced early a philosophy penned by the writer Toni Cade Bambara: “Beauty is care, just as ugly is carelessness.”

My uncle John says another thing distinguished my mother: “I never seen Fannie drink a bottle of beer in my life,” he confesses. “I never seen Fannie with a cigarette in her mouth either. That’s two things I can say for sure about her; she did not smoke, and she did not drink.”

She wasn’t particularly fond of partying either. When she was a teenager, her older brother Napoleon, whom everyone called Flapper, owned a nightclub called Club Zombie, where she worked as a hat check girl. Even though her baby sister Florence and their cousin Annie Pearl loved to hang out at the club dancing and socializing, even selling liquor, Fannie did not. It wasn’t her scene. She was the quiet one.

“Fannie was sidity,” my aunt Florence tells me, shaking her head and laughing. “Honey, she acted like she was too good for everybody. Me and Annie Pearl used to call her Miss Lady.” It was as though she already knew she had plans to “make something” of herself. I suspect a confluence of circumstances led to my mother’s ambition. Although she was a child during the early, harsh 1930s, by the time Mama was a young teen the country had plunged itself into World War II. With the economic boom that sprang from that, black men and women had jobs that would’ve gone to white men had they not been serving in the war. As the second-youngest child of her parents, my mother experienced, if not prosperity, then certainly creature comforts. She already understood the rewards of upward mobility. Plus, she had an ideal role model right there in the home.

As the historian Herbert G. Gutman has proven, African-American families were, contrary to popular belief, intact supportive units in the first decades of the 20th century, and my mother’s home life was no exception. My grandfather, as a self-employed businessman and a property owner, was a powerful force in her life. Because of her birth order as his ninth of ten children, she only knew him as a self-made man (this is not unlike my own life: as my mother’s fifth and last child, I only knew her as a thriving, entrepreneurial, and independent woman), and so the idea of working for yourself, creating your own path, was normal to her. Indeed, witnessing her father’s livelihood, and the self-respect that came with it, was most likely the major factor in her own life choices.

I only heard her speak of my grandfather in glowing, respectful ways; I’m sure that’s why even in her most impoverished days in Detroit, she refused to work a menial job for low pay. To be clear, she always admired hard workers; she just didn’t see the point of laboring to benefit someone else. “If you’re going to work that hard,” she used to say, “you might as well work hard for yourself.”

Meanwhile, throughout the 1930s, the Numbers were all the rage in Harlem, and gaining a foothold in other northern cities like Detroit. According to the authors of Playing the Numbers, the gangster Dutch Schultz’s personal attorney testified that in 1931 the Numbers were “played only by the colored people” and the daily gross was $300,000, or $80 million a year. With that kind of money being generated by the business, of course whites wanted in. Schultz briefly took control of the lucrative enterprise in Harlem, and in Detroit, on the eve of the Great Depression, Jewish gangsters tried unsuccessfully to wrench the business away from blacks. Even still, whites were by then fully involved along side blacks in running the Numbers in Detroit. Italian gangsters looking to diversify during the Prohibition era had moved from bootlegging to Numbers gambling operations, drawn by the huge profits. (This while whites already controlled policy, the illegal precursor to the Numbers.)

On the eve of the Great Depression, Jewish gangsters tried unsuccessfully to wrench the business away from blacks. Even still, whites were by then fully involved along side blacks in running the Numbers in Detroit.

In fact, a scandalous and wide-reaching event that best illustrates how heavily involved whites were in Detroit’s Numbers occurred in 1939, when my mother was 11, long before her own migration to the Motor City. In August of that year, a typist for a major Numbers operation known as the Great Lakes Policy House, Janet McDonald, murdered her daughter Pearl and committed suicide when her boyfriend, a Numbers man, ended their affair. They were found in her car in a garage, dead from carbon monoxide poisoning. Found near her body were six letters she’d written and addressed to local newspapers, the governor, and the FBI, charging that her former boyfriend collected graft money for police protection. The one addressed to the Detroit Free Press read: “Dear Sirs: On this night a girl has ended her life because of the mental cruelty caused by Racketeer William McBride, ex-Great Lakes Numbers House operator.” She then provided McBride’s address and added: “He glories in telling lies, so don’t believe everything he tells you, as I did.” She also implicated law enforcement. In a blaring headline that read “Death Notes Charge Police Bribery,” the Free Press described the spurned white woman as a 33-year-old “comely” divorcée.

When it was all over in June 1942, Mayor Richard Reading, a former sheriff, the police superintendent, 20 police officers (eight of them black), and several “policy operators,” who included boxer Joe Louis’s manager, John Roxborough, were convicted of graft conspiracy in a numbers racket estimated at $10 million a year—the equivalent of $151 million today.

From their inception in Harlem, the Numbers made their way not just to northern cities but to southern cities too, including Nashville; and so by the 1940s, my mother and her siblings were familiar with the Numbers. Surely, Mama occasionally played some numbers as a young woman, even as she soaked up can-do lessons from her father. Family members recall that her older brother Napoleon was briefly a runner. But no one remembers my mother taking any keen interest in the business back then. “I don’t think Fannie fooled with the Numbers down South,” recalls Aunt Florence. “She got in it here, in Detroit.”

That makes sense. Fannie was a colored girl from a good, working-class family of brown-skinned folks, coming of age in the 1930s and 40s. As was the norm, she married her childhood sweetheart, John Thomas Mathew Davis, when she was 18, and within seven months, their first child, a girl, was born. I wonder what my mother’s life choices might have been had she not gotten pregnant, had held off marriage, had been able to do the thing she’d desperately longed to do—attend Vanderbilt University, major in history.

Anyway, two years later, another daughter was born, and four years after that, on their sixth anniversary in 1952, my parents had a son. Fannie was 24, with three children under the age of six. John T., as everyone called him, was 26. Given that my grandfather had taught his son-in-law how to plaster and paint, he had decent, honest work that mostly sustained the young family for several years; but my father wasn’t entrepreneurial, and working for my grandfather didn’t allow him to fully support his own growing family. Nor could he count on the low-paying, menial work available to a black man in the South with no more than a high school education.

Besides, Fannie wanted more. When exactly did the idea to migrate north first take hold in her? Maybe it came shortly after Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, when the Supreme Court got rid of separate but equal education. Maybe that spurred Mama to aspire to more, to trust that certain parts of this country were inching toward making good on its Constitutional promise.

Interestingly, the Confederate flag started popping up everywhere in the South after that landmark decision, and schools remained stubbornly segregated in Nashville despite the Supreme Court ruling. I found online a photo of a woman, Grace McKinley, holding her young daughter’s hand as she walked her to Nashville’s newly desegregated Fehr Elementary School in 1957; she was followed by a white mob, one member holding a sign that read God is the author of segregation. A look of terror is frozen on the face of that little girl, a fate wished upon no child. She appears to be about the same age as my sister Selena Dianne was at that time.

Maybe the idea to leave home came as word spread about good-paying jobs on the assembly lines in Michigan’s autoplants. And the North appeared to be a little bit better, a place where you weren’t forced to live under the mean vestige of “Southern ways” designed to strip you of your humanity. My parents, in their lives in Tennessee, had to speak to all white folks with “yes ma’am” and “yes sir,” and had to withstand being called “gal” and “boy” even as adults. (When we were growing up, one of my mother’s cardinal rules was that we should not call adults “ma’am” or “sir.” “Call folks by their God-given name,” she’d snap. “This ain’t the South.”)

I wonder too if they migrated in part because of incidents of violence against blacks attempting to vote, like that of Rev. George Lee, co-founder of Belzoni, Mississippi’s NAACP chapter, who was murdered by whites in May 1955 for registering African-American voters; Lee was the first martyr of the Civil Rights Movement and my mother and father surely read about his murder in the newspaper, heard about it on the radio, joined in conversations about it with family and neighbors. Did it make them speed up their migration plans, or confirm the rightness of their choice to leave their birthplace, to join others and get the hell out of the South?

As Isabel Wilkerson lays out evocatively in her extraordinary book The Warmth of Other Suns, millions of Southern blacks (my parents among them) were subjected to the indignity of Jim Crow’s “colored only” facilities: elevators; train platforms; ambulances; hearses; waiting rooms in everything from bus depots to doctors’ offices; bathrooms; post office windows; telephone booths; bank tellers’ windows; taxicabs; even betting windows at the racetrack. Colored drivers had to let a white person go first at an intersection, could not pass a white motorist on the road, were always at fault in an accident; my mother and father could not speak to a white person unless spoken to, or attempt to shake a white person’s hand. Indeed, my parents understood that “the consequences for the slightest misstep were swift and brutal,” as Wilkerson writes.

Given the micro- and macro-aggressions of Southern life, coupled with their own aspirations, they saved hard, and Fannie and John T. left the only home they’d known, the place both their families had lived for generations—my maternal great-grandfather Phile Thompson was born into slavery in Nashville in 1861—and became the first ones to migrate north, after my uncle John. They boarded a train and went where the Tennessee Valley Railroad line took them, more than 560 miles away, to Michigan.

My parents were, as Wilkerson eloquently notes, part of “a human rivulet, and then a flood of six million black refugees fleeing the terrors of the Jim Crow South . . . to an uncertain existence in the North” in what became known as the second, postwar wave of the Great Migration.

__________________________________

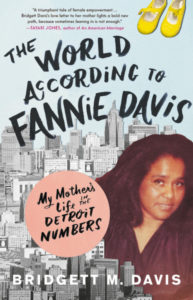

From The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers. Used with the permission of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2019 by Bridgett M. Davis.

Bridgett M. Davis

Bridgett M. Davis is the author of the memoir, The World According To Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life In The Detroit Numbers, a New York Times Editors’ Choice, named a Best Book of 2019 by Kirkus Reviews, and featured as a clue on Jeopardy! She is author of two novels, Into the Go-Slow, and Shifting Through Neutral. Davis is also writer/director of the award-winning film Naked Acts, which was recently re-released to critical acclaim. She is Professor Emerita at Baruch College (CUNY) and the Graduate Center, where she taught creative, narrative and film writing. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the LA Times, among other publications. A graduate of Spelman College and Columbia Journalism School, she lives in Brooklyn with her family.