A few years ago, when I was 27, I left my job as a corporate lawyer in London and moved to Warsaw to write a novel. I knew how irrational this move was, how laughable my chances of success. But my need for reconciliation was so desperate it had outgrown my fear.

In 1981, around the same age, my parents had fled Poland. As young graduates with no contacts in the Communist Party, they’d tried to make do with the empty shops, the endless queues, the hopeless, underpaid jobs. They saw no other way to live but to leave. They managed to obtain passports and took a bus, crossing the border from East into West Germany. A few months later, martial law was declared in Poland. The country’s borders were sealed and tanks began to roam the streets. Political dissidents were jailed and tortured, as the regime imposed by Stalin struggled for survival.

Almost a decade later, once the Wall had come down and the country opened itself to the so-called Free Market, we were able to return, to visit the friends and family left behind. We’d go to see my grandmother in Wroclaw or an Aunt in Warsaw. My parents sent my sister and I to Catholic summer camps. I spoke the language, yet I felt like an alien. I dreaded the country’s greyness, the rusty playgrounds, the sound our car made over the cracked roads. It was there, at barely six years old, that I was first called “faggot,” by some boys at a camp. I didn’t know the meaning of the word, but I sensed it was something shameful.

A small part of me still believed that Poland wouldn’t want me or my story about two young men falling in love under Communism.

This shame followed me for a long time. Throughout my teenage years I repressed my sexuality, convinced it would disappoint my parents, that it was somehow inconsistent with my origins. Over the years, my trips to Poland became increasingly rare. I would shudder at the thought that I could have been born there. I resented my relatives and their enquiries about my lack of girlfriends; I was insecure about my accent, my difference. I knew I didn’t fit in, and I was terrified of having it pointed out. Once, at Warsaw’s Zachęta National Gallery of Art, I asked a security guard, a middle-aged man with a mustache, for help finding the nearest restroom. He gestured toward a corridor, then looked into my eyes and said: “You’re not Polish.”

But who gets to decide who you are and where you belong?

In my early twenties, while I was interning at the United Nations, I found myself living in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The neighborhood’s Polish diaspora came as a revelation. It was freeing to walk the streets among people like me, who couldn’t judge me for my foreignness, who were also neither here nor there. And it was here, while living in this foreign but familiar place, that I first came across James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. I had recently gone through the painful process of coming-out to my parents and Baldwin’s exploration of shame, his depiction of its corrosive power, shook me to the core. It felt like the first book I’d ever truly read, the first that spoke directly to me. It made me see just how dangerous it is to run from the past.

Over the years that followed, I lived in many different countries, worked a variety of jobs, but the more I thought about my personal and familial history, the more it struck me how arbitrary our birthplaces are, how arbitrary privilege and our sense of self really is. I began to imagine what my life would have been like had I been born just a little earlier, in my parents’ country. Could I have lived and loved in dignity in Communist Poland? What sacrifices would I have had to make? And would I have, invariably, yearned for the freedoms of the Capitalist world?

So I returned to Warsaw, determined to write a novel that would help me find answers. I walked the streets of the former Jewish ghetto, built over with concrete housing blocks, rode the tram through the working-class Praga district, where, like stars, bullet holes from WWII still adorned the façades. I explored the elegant neighborhoods south of the center. Who had lived in these vastly different homes, I wondered, when everyone was supposed to have been equal under the former system? And what had they done to get there?

Throughout the writing process, I rediscovered the Poland of my childhood, the food I’d loved, the bucolic summers. Memories of my grandmothers returned, and with them a sense of belonging. I started calling my parents more often to talk about their childhoods or ask about relatives I’d only rarely heard of. I reached out to activists and consulted archives, seeking to uncover what life must have been like for queer people under Communist rule. The personal and the collective began to coalesce.

“Don’t ever listen to those that will criticize you or question your entitlement to this country.”

Ludwik, the young narrator of my new novel, goes through a similar conflict as my own: he questions his sexual identity as well as his relationship to his homeland. He, too, is able to draw solace from Baldwin’s novel, which existed as an underground translation in the Soviet Bloc. The book connects him to the wider world, lets him know that his shame is something others have lived through before.

These days, such need for comfort and reassurance continues to be a necessity. As that peculiar mid-point between Berlin and Moscow, Polish society finds itself torn between tolerance and “traditional” values. Out of fear, countless LGBTQ+ people still hide their true identities from their families, friends, and colleagues. But this conflict also mirrors a global phenomenon, one that spares next to no country.

*

Now I live in France with my husband. When my novel was finally bought by a Polish publisher, I returned to Warsaw for the launch party, which was set to take place at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, the site of my earlier shame. A small part of me still believed that Poland wouldn’t want me or my story about two young men falling in love under Communism.

It was a cold Friday night when I stepped into the Gallery’s stunning main hall, built in the 19th century by the society for the encouragement of the arts (“Zachęta” means encouragement). It was packed—Poles of all ages and genders were sitting on chairs and on cushions all the way to the top of the central staircase. Many were standing. I was taken aback.

After the discussion, a long queue formed for the book signing. Never before have I been met with so much well-wishing, with such expression of sympathy. While I was signing her copy, one woman said to me: “Don’t ever listen to those that will criticize you or question your entitlement to this country.” I was surprised, but not so much by her kindness as by the realization that I had already known this. I had figured it out for myself.

__________________________________

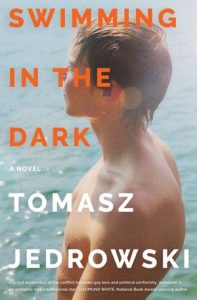

Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski is available now via William Morrow.

Tomasz Jedrowski

Tomasz Jedrowski is a graduate of Cambridge University and Université de Paris. He was born in Germany to Polish parents, and has lived in several countries, including Poland, and currently lives in Paris, France, where he works in high-fashion. He speaks five languages and writes in English. Swimming in the Dark is his first novel.