On Working as a Black Journalist and an Advocate for the Black Lives Matter Movement

Janna A. Zinzi on Justice, Censorship, and Activism

On a sweltering Saturday morning in Phoenix, hundreds of “progressive” leaders and activists from around the country gathered for the main event of Netroots Nation 2015. It was supposed to be a presidential forum of the Democratic candidates, but only Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley attended. Hillary Clinton didn’t seem to think it was necessary to show up or even send a video (insert eye-roll emoji). Young white guys lined up all morning to get a seat at the front of this conference center auditorium so they could be close to their beloved Bernie. Folks were even dressed up in Robin Hood costumes to represent the redistribution of wealth and economic equality, Sanders’s foundational talking point. Out there looking like it was Comic-Con.

Only a few days earlier, Sandra Bland was murdered by police in Texas. Mourning Black death was no novel feeling, but this hurt differently. Likely because she was a young Black woman, and we saw ourselves in her. She was/is us, our sister, our cousin, our homegirl. While her death and police violence were important topics for the Black attendees, Netroots is typically a very white tech bro space. Her murder went unaddressed in most plenaries or sessions. It was business as usual for white folks—even the “liberal,” social justice–minded people who genuinely care about democracy. In response, Black organizers got together and planned an action during the presidential forum. We wanted to know the candidates’ stance on police violence against Black people and ask them on the spot to address this very real and overlooked issue.

We wanted to know if they actually believed that Black lives matter.

Several Idas* were at that Netroots. We came through as a squad and were busy hosting panels, running workshops, networking, being bosses. And we were most certainly going to participate in any action that elevated the voices of Black women amid a backdrop of white silence.

So when it came time for the presidential forum, a significant bloc of Black folks attending Netroots, as well as local activists, sat together in the back of the auditorium. I felt an exhilarating yet tense energy, currents of adrenaline pumping through us. Although we’d practiced for this action the day before, gathering at a local soul food restaurant to organize, share information, and break biscuits, I wasn’t prepared for the reaction we got from the audience. When our group of dozens of Black comrades marched in two lines toward the stage asserting “Black Lives Matter,” many people were angry and stunned. Their casual disregard and privileged blind spots were on full display . . . written all over their smug faces. Many a white boy was PISSED that we had the audacity to interrupt their messiah.

We wanted to know if they actually believed that Black lives matter.

I stood on a chair in front of the stage, proudly sporting my marigold-colored Echoing Ida T-shirt, and recorded the whole incident. Idas, including Shanelle Matthews, Gloria Malone, and Amber Phillips, walked to the middle of the auditorium with other Black women activists for the most evocative and gut-wrenching aspect of the action. One by one, they stood on a chair and shouted their response to the prompt, “If I die in police custody . . .”

If I die in police custody, I want you to know I was murdered.

If I die in police custody, tell my daughter how much I love her.

If I die in police custody, keep fighting for justice.

Say my name.

Don’t stop until we are free.

In return, our fellow conference attendees yelled at us to shut up, sit down, move out of their way, and let Bernie speak. A Latina dressed in a Robin Hood outfit was chanting, “We hear you,” which was ironic and maddening because you can’t hear anything if you’re yelling over us. A young white woman asked me if I was okay and said she had my back. I wanted to believe her but was shaking with anger. I wonder if she understood how unsafe I felt surrounded by people who refused to acknowledge our humanity. When Sanders continued to try to deliver a stump speech about economic inequality despite being asked about his stance on police violence, we rolled out. Some people in the audience left with us. Some booed at us or clapped that we were leaving. A few people thanked us for educating them.

This event activated many of us in what is now known as the Movement for Black Lives. It also gave us permission to play a dual role as writers and activists. In journalism spaces where objectivity is a foundational principle, many Black writers cannot use their voices in dissent or visibly take a “political” stance. But what do you do when your life is at stake?

This has become a critical conversation in 2020 public discourse for Black journalists covering the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and other Black folks who have been killed for minding their own business.

Fast-forward to 2017, another sweltering summer day but this time at the National Association of Black Journalists annual conference in New Orleans. It was the first time members of Echoing Ida attended as a group, and we felt excited and curious about being in a professional writing space as opposed to an advocacy-centered conference. It was certainly a more polished and “respectable” vibe than our typical conferences, but we attended panels discussing advocacy in journalism and Black women’s reproductive health and justice. We ate oysters and drank cocktails in the street; it was dope.

But the good times stopped rolling when former reality TV star Omarosa Manigault, the newly crowned director of communications for Trump’s Office of Public Liaison, got added to the schedule as a last-minute addition. In the most disrespectful fashion, she was added to a panel titled Black and Blue: Raising Our Sons, Protecting Our Communities, which was about police violence with relatives of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling. This after her president encouraged police at a rally to rough up suspects even more (translation: fuck up Black and brown folks). High-level gaslighting and totally on brand. Nikole Hannah Jones of the New York Times and Jelani Cobb of the New Yorker were supposed to participate but pulled out when Omarosa was added. Shout out to them for not participating in a propaganda shit show.

In journalism spaces where objectivity is a foundational principle, many Black writers cannot use their voices in dissent or visibly take a “political” stance. But what do you do when your life is at stake?

The panel ends up being in a room that can accommodate maybe a quarter of the conference, making it impossible for a couple of us Idas and dozens of attendees to get in. I was fussing HARD for a moment, but after a smoke break, Jasmine Burnett and I made our way in. We squeezed into a row with fellow Ida Renee Bracey Sherman and sat with some prominent Black women in politics and punditry, including Brittany Packnett. As Omarosa deflected questions about her culpability in the Trump administration’s reprehensible support of police violence, Packnett stood up and put her back to her. I’m pretty sure many in that room wanted to do the same but that could have put their jobs on the line.

We stood up too with our backs to Omarosa, who maintained a pompous and dismissive attitude toward legitimate questions like, “What have you done for Black people lately?” A few other journalists joined the protest, but what I remember most is facing the audience: a sea of good-looking, smart af, professional Black media folks who were livid. Some were shouting retorts against her lies. Some left the room entirely. Some were furiously typing but pretty much everyone was unimpressed. After it was over, many attendees thanked us, which felt strange because why wouldn’t we do that? It was then that I understood the challenge of being a Black journalist tethered to “objectivity” when our lives are literally at the hands of misinformation.

The political moment of 2020 is illuminating all of the hypocrisy within our movements and that anti-Blackness is inherent in all of our systems, whether it’s media, politics, entertainment, or social justice. In the spirit of Ida B. Wells, it is our mandate to speak out against injustice and anti-Blackness, whether with pens, laptops, or our bodies. We do not just write about activism or justice for our communities; we also take action, even when we are afraid. When we are called to show up, we also show out. Free speech is a privilege we don’t take lightly. We voice uncomfortable truths for our folks who can’t due to real threats of retaliation. We protest for our people challenging the status quo from within our toxic institutions. The double consciousness of Black life in America is exhausting. Censorship—even self-censorship—in the name of “objectivity” can no longer eclipse our humanity.

*In honor of Ida B. Wells.

__________________________________

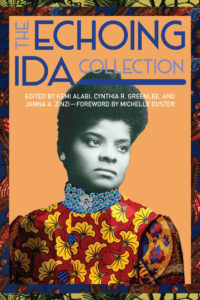

From The Echoing Ida Collection, edited by Janna A. Zinzi, Kemi Alabi, and Cynthia R. Greenlee. Used with the permission of Feminist Press. Copyright © 2021 by Janna A. Zinzi.

Janna A. Zinzi

Janna A. Zinzi (also known as jaz) is a strategist and storyteller documenting cultural changemakers in arts, spirituality and social justice. She’s the co-founder of WanderWomxnTravels, a travel space for radical travelers who want to have local and international adventures and make cross-cultural connections. jaz is also an international burlesque teacher, performer and mixed media artist focused on supporting women and non-binary people in activating and accentuating their sensuality.