On Unjustly Forgotten American Abstract Artist Alice Trumbull Mason

Meghan Forbes: What the Letters Reveal About the Artist

Reading the letters of someone who has passed is always a delicate matter. And writing about their once-written words is to exhume histories that lay dormant. It involves a summoning of ghosts and a conjuring of voices.

Alice Trumbull Mason appeared to have been conscientious of her letters’ importance in constructing her legacy, taking care to preserve them. In a letter to her mother written while traveling in Italy and Greece in 1929, Alice scrawls at the top of one page, “P.S. Please be sure to keep my letters – for me – thank you –.” The instructions were heeded, and today, in the studio of her daughter, the artist Emily Mason, are shelves full of black binders that hold her letters of Alice. These include those she sent to her husband, Warwood Mason, and lover, Ibram Lassaw, as well as to Emily, and those she received from artist colleagues such as Josef Albers and Piet Mondrian.

A period of correspondence with Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, and William Carlos Williams also points to Mason’s early literary ambitions. Williams had offered encouragement and edits to a poem entitled “Trees,” which would ultimately be published in the Winter 1931 issue of Pagany. Around the same time, Stein responded to some writing Mason had sent her with the evaluation that she showed “some genuine poetic impulse and understanding.” The letters in the archive show that the two women corresponded for at least a few years. In March of 1931, Mason, newly married, writes to Stein from West Harlem that “You know your letter did me good” and in 1933, now also a mother, she reports from a stay in Jersey City, “your books & the contact with you have done a lot to clear the air.”

Reading Alice’s letters is an opportunity to know this woman as she wrote herself, to better understand her as an artist on her own terms, through the words that she wrote privately about her practice, and the not-unrelated subjects of literature, love, and loss.

“Well I finally cracked up enough to scare me into being more sensible.”

While so little has been written about this artist in her lifetime and in the decades since her death, primary source documents in the archive of Mason’s estate—letters, photographs, and diaries—now help in correcting this paucity of published information, in constructing a narrative of her life and work in retrospect. The letters serve not only to fill in the gaps or correct errors in the artist’s biography, but also build a playful, as well as melancholic, portrait of the artist, who presented different versions of herself depending on the recipient.

*

To her husband, in the early days of their courtship, Alice is all aflutter; she calls him “Honey man,” or, “Honey love.” She says, “Warwood (my honey) aren’t we a blithe two? Isn’t it, don’t we, and ain’t we got fun… my mind is full of ships and gaiety and dream, with a glimpse of secret adventures popping in and out.” Ships are a key motif in their story; he a Chief Naval Officer often at sea, she his bride anchored early in New York by pregnancy. Within the first year of their marriage, she is with child. “Honey darling—I have a little frog inside of me,” she writes in September 1931. And the following month: “Honey man—Here I sit in our little nest (hatching I suppose).”

Already in early pregnancy, Alice expressed the tension between a desire for companionship and a solitude in which to work. To Warwood she writes: “Believe me I’m going to paint furiously this summer and fall—after that it may be a long time before I do again—what with feeding and washing & airing and all that. […] Anyway it’s going to be heavenly having a new friend all full of imaginings and secrets, every child is like that for a few years—and afterwards I’ll be free to paint again.” Fifteen years later, in the summer of 1946, with Emily off at summer camp, Alice writes to her daughter, “I love you and am longing for you to be coming home again. What a lot we will have to talk about. Naturally I am longing for you, while at the same time I want you to stay and have a wonderful summer and for me to have plenty of time to work.”

Alice did manage to maintain her dual roles as mother and artist, and in fact, over time, nurtured the “imaginings” in her “new friend” such that Emily would also become a painter. From her letters, we witness Alice cultivating her daughter as an artist from an early age. She writes to her on multiple occasions of her impressions of Virginia Woolf. When in college, in the fall of 1950, Emily is assigned to read Mrs. Dalloway, her mother offers her own review, describing it as “a very good book, but I think you would be more at home in To the Lighthouse, which is more difficult in some ways, but by that fact, much easier to comprehend if you are an artist.” Already she sees her daughter as an artist, like herself.

Once Emily is old enough to be away from home, and letters become a frequent mode of communication between mother and daughter, Alice articulates her thoughts on literature and sends updates on her painting. These letters offer an intimate insight into her artistic practice, as Alice records how she simultaneously endeavored to nurture a family while maintaining a fierce professionalism and commitment to her craft.

In the summer of 1949, Alice describes for Emily the New York City heat and the impact that it is having on her painting: “I am very absorbed in my new paintings. I am on the second, now, and intend to make about 6 more on this problem of contraction and expansion. The colours are muted and white and black and yellow, with variations. The one that looks the coolest was painted in the hottest week. 2 weeks. You saw it.”

When Alice talks about her painting in her correspondence—and not only with her daughter—it is often within the context of color, and specifically how particular colors reflect her physiological and mental state. In a letter dated only “Labor Day” (but likely written in the late 1930s or early 1940s), Alice writes to her lover and fellow artist Ibram Lassaw that, “I am getting started on a new painting, which is a help to my bottled and battling self, it is full of staring yellow. Very satisfactory to work with, at this time. I’ve never seen yellow used like this before, it has a tremendous impact.”

And in a more playful gesture, in a letter to her husband dated November 17, 1936, Alice offers him a color “code we can use for Xmas & it will tell more to each other.” The list starts out predictably enough—“Red = I love you passionately & adore you & love u love u love you, Yellow = I am not well”—but further colors connote a more nuanced state of affairs. These additional items provide hints not only into the emotional valence she ascribed to certain colors, but also into Alice’s struggles with drinking, an understanding that her husband may be tempted by other women on his long bouts at sea, her oft repeated wish that he find a different job, and her own professional ambitions. Along with a request that he return from his current voyage “sober & well slept because I am going to have things to do to you” she offers the following list:

Black = I wish we were in bed & doing things to each other

Blue = a new exhibit is in sight (Or for you a new very nice job!)

Pink = I’m on the wagon and haven’t fallen off

Rose = I’ve stayed pretty well on the wagon, tho I’ve drunk or been drunken once or twice

Lavender = There’s been nothing exciting – or there are many old ladies aboard (and nothing exciting!)

Alice’s self-understanding and interpretation of circumstances seems to have been perpetually filtered through her art. She saw the world in color and image, and time taken up by the demands of daily life was time that might have been spent painting (or reading or writing). In a letter again to Emily, now from March 1957, and as her daughter is preparing to marry, she closes enigmatically: “About that silver sliver of sea, it is full of symbols, but I just felt like painting a story. Would rather have done that tonight. Next time, maybe.”

*

Alice had a son, too. Jo disappeared in 1958—just around the time that Emily was married—and was later found dead while serving as a merchant marine. It is a testament to how clearly she considered her letters a legacy that none survive between him and her, though he is often mentioned when she writes to her daughter or husband.

In her letters, we see that Alice considered herself first and foremost as a painter.

In March of 1958, Alice sends a letter to Emily, then living in Italy, from the Park West Hospital, on stationary that bears the logo of the American Export Lines and in an unsteady script that betrays her inner turmoil. She writes, “Well I finally cracked up enough to scare me into being more sensible. I’m suffering from malnutrition, fatigue, too much alcohol and a touch of bronchial trouble enough to run a fever. […] This my break up stems from my misery over Jo and lack of sense. I gradually ate less and less, but drank more and more.” Despite her state, however, she does not lose her artist’s eye, mentioning that she has a friend bringing in a painting to replace the “foul thing” currently hanging in her private room. Books also remain central, as she reports that she is re-reading Finnegan’s Wake and “enjoying the luxury of no must do.”

In a subsequent letter from June, Alice’s shaky hand is replaced by the typewriter, the machine creating an impersonal sheen to her emotional pain with its perfectly standardized construction of letter forms. Having closed a cab door on her thumb, she reports, her hand is in a splint, but “In spite of my disability, I can paint, cant [sic] write very well.” Alice hopes her injury will not be too much of an obstacle because “this painting job coming up is going to be a honey.” Despite great personal trauma, Alice would not interrupt her art practice, and continued to work steadily as a painter until her death in 1971.

*

In her letters, we see that Alice considered herself first and foremost as a painter and always had confidence in her rightful place within the context of the history of early American abstraction. Towards the end of her life, in 1969, Mason wrote a letter to Thomas Hoving, then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her hand-written note is on the letterhead of the American Abstract Artists, an organization which she had helped to found and of which she was president at that time. The purpose of her letter is to thank Hoving for recent attention given by the museum to modern works of art, and she takes the opportunity as well to affirm her own place within the history of American abstraction. “Having been an abstract artist since 1929,” she writes, “I am certainly very happy that the Metropolitan Museum, under your guidance, is showing works of this nature. I am enclosing a brochure of my two 1967 solo shows, which indicates that I am represented in all the big collections, though sometimes only by a print, either etching or colored woodcut.” Mason duly compliments the director, while at the same time gently suggesting that the museum would do well to collect more of her work.

Despite her sustained efforts, the only painting by Mason owned by the Met today came into the collection in 1976 as a gift of her daughter. The museum also holds a few prints, as does the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim owns two paintings. The Whitney Museum of American Art boasts the stronger collection, and put on a solo show of her paintings in 1973, though it has exhibited her work only once more since then. But if it is taking the museums and critics some time to catch up, no matter, because Alice knew her greatness all along.

All quotations in this essay are cited from letters held in the archive of the Estate of Alice Trumbull Mason.

__________________________________

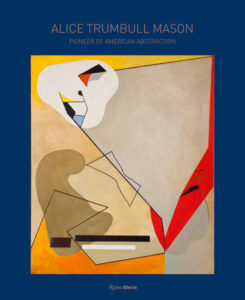

Alice Trumbull Mason: Pioneer of American Abstraction by Marilyn Brown, Elisa Wouk Almino, and Will Heinrich is available via Rizzoli.

Meghan Forbes

Meghan Forbes writes about modern and contemporary art and literature, makes books, and composts food scraps in Brooklyn.