On Translating Poems While Riding the Metro in Rome

Damiano Abeni: Transforming Texts as a Performing Art

The translator is a close reader.

–Charles Simic, Snowy Morning BluesArticle continues after advertisement[…] Or else: all is translation

and every bit of us is lost in it

(Or found […]

–James Merrill, Lost in Translation*

Under the buildings—tufted clay, / Like tennis courts upended—runs the subway of Rome. I have been riding it for 36 years, on weekdays, to get to my workplace: a public health institute early on, a research hospital since the new millennium. The trip is 25 to 35 minutes, passing through 12 stations, and usually after a couple of stops I get to sit down. That’s when I can open my poetry books and the notebooks in which I translate them, while men and women come and go talking of the frozen fish they’ll have for dinner.

Until recently, there was no signal, no field, in the trains—no google, no online dictionaries—and I still pretend it’s that way: in the absence of field, I am the field. I feel very close to Glenn Gould, who said something like, “I’m sure I have never played as well as when I was practicing at home, while the housemaid was vacuuming around the piano”. This radical dichotomy between purpose and environment for me absurdly works like a shipwrecked transcendental meditation, I find myself on an island that seems to be / a sort of a cloud-dump. Without giving way to self-pity, I start to sort through that dump. Kind of daydreaming, I gather all my ways of knowing: reason, perception, memory, language, emotion, intuition, imagination, peppered with a bit of courage, and even faith—which is weird for one who sleeps on the top of the mast / with his eyes fast closed.

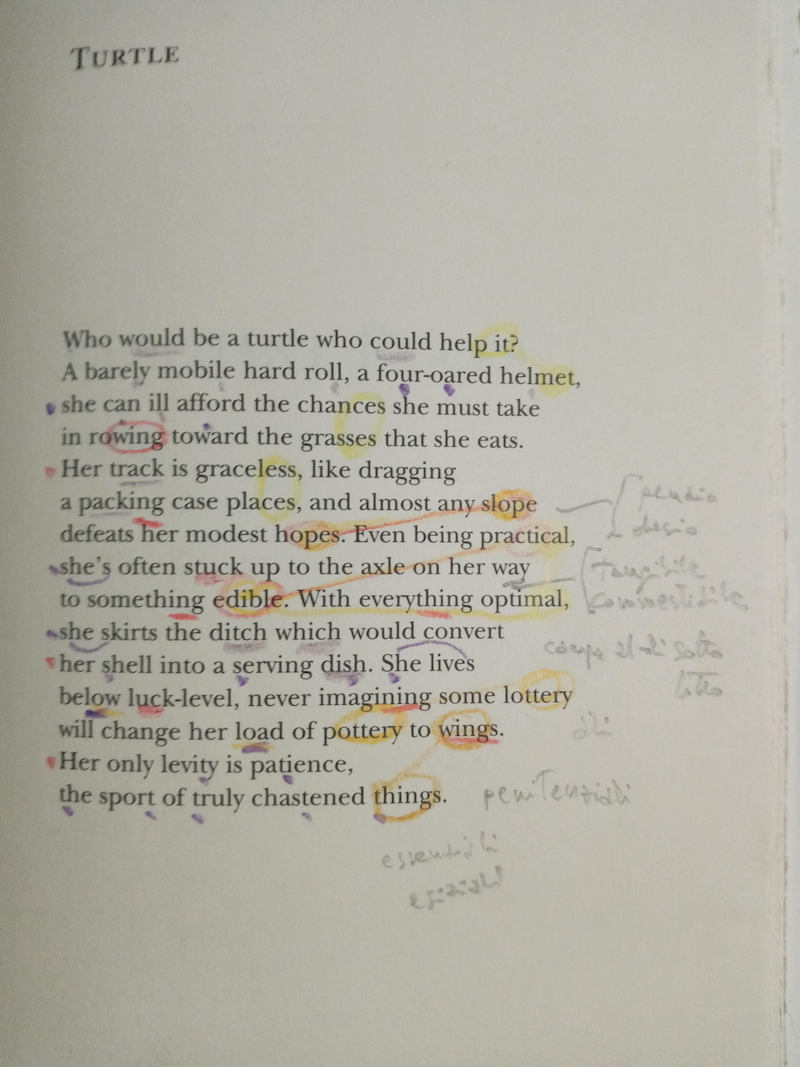

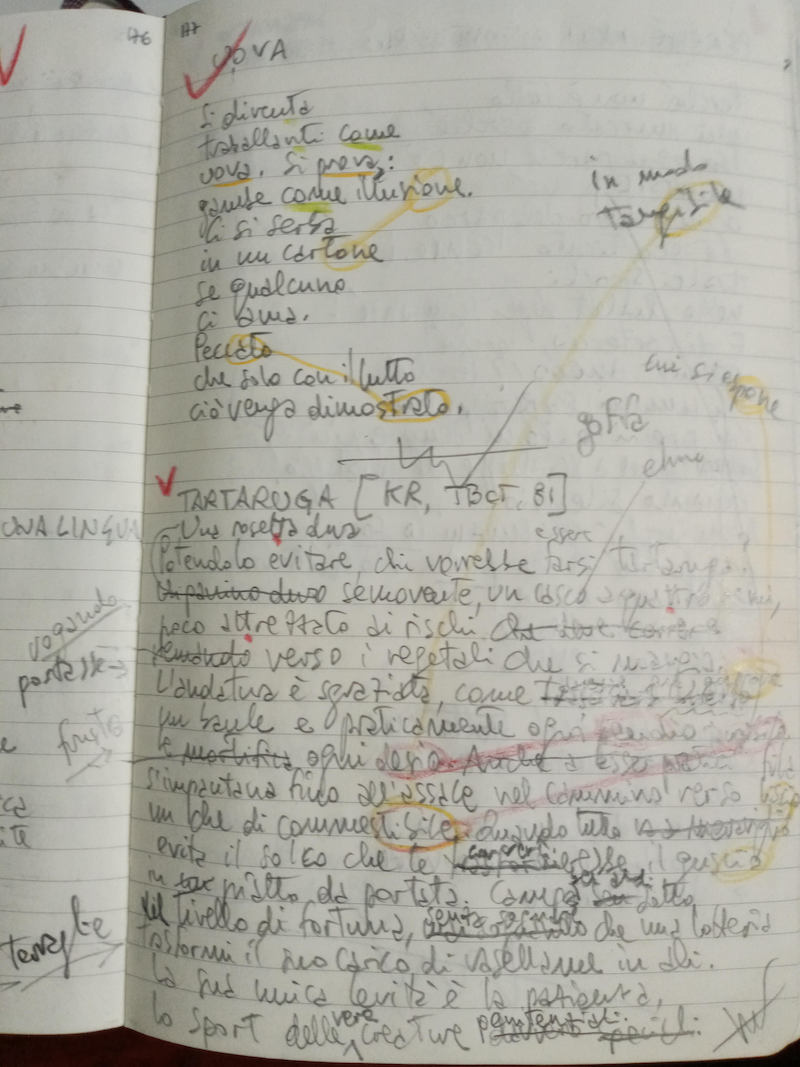

First I look at the poem, without really reading it. Just observing it, as an animated concrete object, trying to understand how it is made. Not only because Wystan Hugh Auden told the archangel Michael, James Merrill and David Jackson attending the lecture, LORDS: / THE TRUE POET IS, OF ALL THE SCRIBES, MOST DRAWN / TO THE CONCRETE. YES SIRS, WE THRIVE ON IT!, but because of the very etymology of the word “poet”—ποιέω, I make: makar, maker. My first question is, “what’s going on here, what is the poet doing?,” not “what is the poet saying?” Each word, each syllable, each letter, each accent matters, in itself and in its relation to all other words, syllables, letters, accents. Leopardi said (and I seem to remember he was quoting Pindemonte, but don’t quote me on this): “Words are the body, not the clothes, of thought.” So I take out my array of colored pencils, very limited compared to the one I can use at home, and start to paint the poem: same color for prominent letters in assonance, consonance, rhyme, slant rhyme; lines connecting the same/similar looks, same/similar sounds. . . I try to portray visually the rhythm, the music of the poem. This trick came to my mind just looking at the cover of Dylan Thomas’ anthology The Colour of Saying: if words, on the page and when spoken, have a color, we should be able to see it!

Now my eyesight is bad enough that I don’t need to do this anymore, but early on I would go in a copy center and have the poem xeroxed, in color of course, and enlarged. I would then paste it to a board, and watch it from across the room in order not to see the words but instead the patterns. There! I’d see the stillness moving, paint-shape of object and sound, and the surrounding void / these object-sounds sentry for, and rise from. I look at it talking to me, like a developing photograph. I have it but I don’t have it.

Two more quick steps will have to be taken at home: 1) read the poem aloud, giving actual sound to the colors; 2) type the poem, paying no attention to the words but trying to perceive where your fingers roam, which parts of the keyboard are most often visited, which letters and sequences and patterns of letters.

Moira Egan, my wife, in her bilingual book Strange Botany—published in Italy by Pequod in 2014—has perhaps unconsciously depicted parts of this process, looking at me while I’m looking at a geranium plant:

[…] he pays attention

to the less conspicuous

elements, passing right

over the fuchsia blooms,

for example, to see

if the leaves harbor parasites,

whether the soil’s properly

moist or dry. It’s the way

he bends down, as if in

veneration, takes hold

of the pelargonium’s deep

green, crushed-velvet leaves and strokes

a handful of fragrance

from them. […]

Now, burdened about beauty you have to / come out into the open, and work. May I be made into the vessel of that which / must be made.

As the / green pasture / of the mind / tilts abruptly, I wait for a free seat (much rarer now, with distancing), I open my notebook and start to look at the poem with new eyes—all the previous work stored in a toolbox: I studied, I have practiced, now it is time to perform.

Kind of daydreaming, I gather all my ways of knowing: reason, perception, memory, language, emotion, intuition, imagination, peppered with a bit of courage, and even faith.

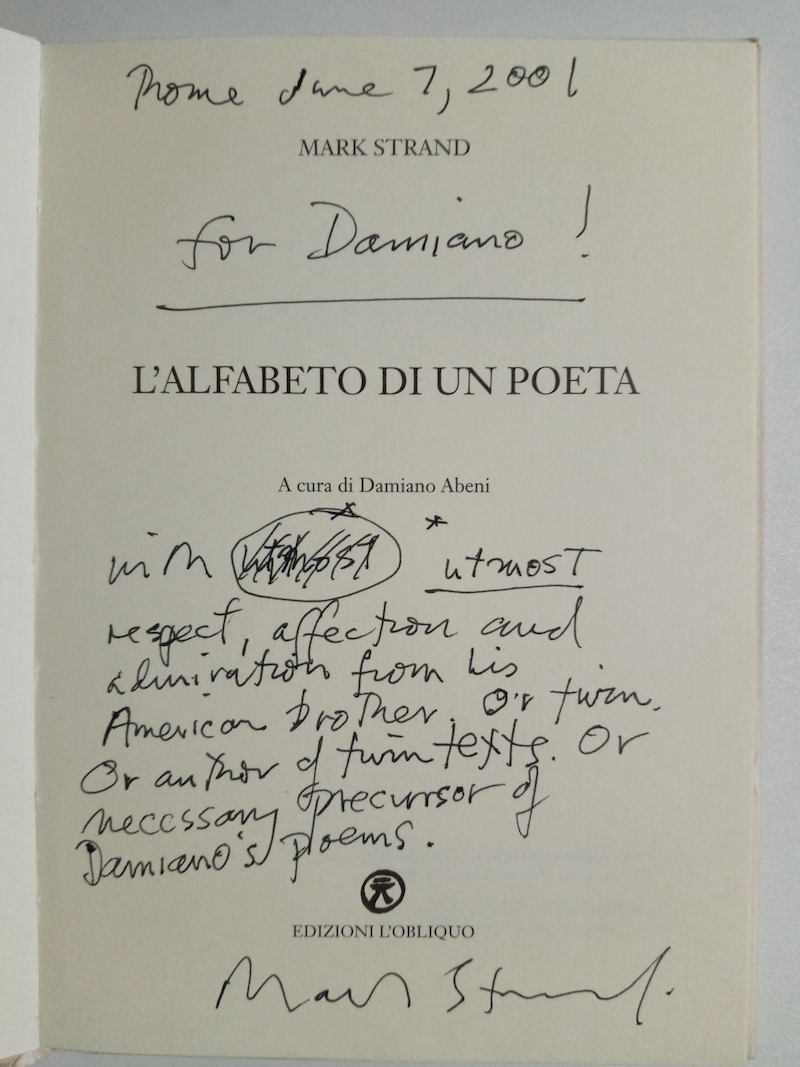

I see translation as a performing art. Though translators use the same tools as writers—pens (I actually use pencil, it has a component of malleability which makes for a more intimate contact with paper), paper, keyboard—they are doing something completely different. There is a necessary rational component in translation, an exaggerated accumulation of attention, that in writing could hinder creativity. Mark Strand told me once, “I don’t try to completely control what I do when I write a poem. If I did, the poem could not be better than what I am. And I’m not that good of a person.” To put it in other words, this is an exchange that happened with Moira a few years ago. We were in Santa Teresa di Gallura, Sardinia, where thanks to the home my parents built we can stay in writing-and-translating residence for part of the summer. Our meals are blessed by the incredible local produce and the sublime, fierce Sardinian wines. After lunch Moira asked me if I wanted another glass: I said, “If I drink another glass of that Cannonau I won’t be able to translate anything,” and she replied, “If I don’t drink another glass of that Cannonau I won’t be able to write anything.”

So here Glenn Gould comes back to help me, with his painstakingly controlled creativity and his unique sense of the expression of time, and tone, and dynamics. And his vacuum-cleaning housemaid. We have to have the music inside of us to put it on the page. We have to consciously stray from the academic path of excessive concern with meaning, the professorial concern—the dread of mistakes (“that is not the same word, it’s wrong”)—that makes for very stiff texts, terribly far from the actual entity of the original. We have to avoid the language that poet friends, and translators, call “translatese.”

It is true that translators find themselves in the position of putting up the sign “don’t shoot the piano player,” as they are so easily and so often criticized. And here I will, immodestly, cite again Mark Strand: “I have been translated in maybe 20 different languages, and I have read in maybe 40-50 different countries,” he said to me, “and every time, after the reading, someone would come up to me and say something like, ‘I love your poems, but I could have translated them better.’ That has never happened in Italy.” And one of the greatest compliments I ever received was from a ten-year-old boy, son of Anglophone friends. The child was born in Italy and is perfectly bilingual: after a reading of Moira’s poems and my translations—to which his mother dragged him along imagining that he would be terribly bored—he came up saying something like, “Damiano is very good, because he doesn’t use the same word, he uses the right word.”

Translation is a prolonged event that the oeuvre has been waiting for, to be reborn in a different space from the one in which it was originally conceived.

I drastically claim the right to call my translations poems. Away from the ambiguous Umberto Eco’s subtitle “to say almost the same thing”, I assert the uniqueness and radical originality of a new object springing from a given form and meaning. Nothing like my translations exist in Italian, for the excellence of translator depends on exploiting the unique opportunities of their native language.

So I have come this far on my own legs,— / not missing my subway, /climbing always. One foot in front of the other, / that is the way I do it—to dwell in cold pockets / of remembrance, whispers out of time.

*

The materi-

als, the pia-

no prepara-

tions, were chosen

as one chooses

shells while walking

–John Cage, Silence

Why am I doing this?

It was 1973, I was an AFS exchange student in Tucson, AZ. Of course, no internet back then, and phone way way too expensive—I talked to my parents in Ospitaletto, Brescia, Italy, twice over the whole year. We sent letters.

Every Tuesday I’d send a letter to one of my friends. Part of it was intended just for that person, and part was like a newsletter he/she would share with the other friends. In the “public” part I started adding a translation, mostly from beat poets (they were immensely popular in Italy at that time) or songwriters (i.e., Bob Dylan). In turn they started asking me to translate lyrics from progressive rock bands—like Genesis, Jethro Tull, King Crimson, Van der Graaf Generator, you name it—or more beat poets.

It was my way to communicate what was important to me at that time, to share experiences, and it has been like that for 47 years and over one hundred books. It’s my way to be a storyteller.

When, years later, I became more aware of what I was doing, I felt I was actually striving to follow closely Italo Calvino’s commandment: “[…] seek and learn to discern who and what, in the midst of hell, are not hell, then make them last, clear a space for them.”

Why do I tell you these things? / You are not even here.

__________________________________

From TRANSLATING IN THE SUBWAY – Almost a Cento by Damiano Abeni. Used with the permission of Edizioni Black Coffee. Copyright © 2020 by Damiano Abeni .

Damiano Abeni

Damiano Abeni is an epidemiologist. He has been translating American poetry since 1973, when he spent a year in Arizona. He collaborates with numerous publishing houses and literary magazines, and is an honorary citizen on cultural merits of the cities of Tucson, Arizona, and Baltimore, Maryland. He lives in Rome with his wife, the poet Moira Egan.