On the Timeliness—and Timelessness—of Muriel Rukeyser’s Far-Reaching Poetry

Natasha Trethewey Considers the Essential Role of Poetry in Our Lives

My earliest encounter with the poems of Muriel Rukeyser was in a seminar on contemporary American poetry in my first year of graduate school. It was 1990, she’d been dead for ten years, and as I read aloud from “The Book of the Dead”—a long sequence from Rukeyser’s 1938 collection U.S. 1—I felt the resonant power of her living voice, and the recognition that came to me was like the lightning that accompanies a thunderclap, illuminating everything for a resounding moment:

As dark as I am, when I came out the morning after the

tunnel at night,

with a white man, nobody could have told which man was

white.

The dust had covered us both, and the dust was white.

The sequence recounts the history of the industrial tragedy of the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel construction project in Gauley Bridge, West Virginia. Rukeyser journeyed there to report on what had happened: industrial greed and malfeasance, the unsafe working conditions in the mines, the many deaths from silicosis (a disease that causes shortness of breath and is the result of prolonged inhalation of silica dust) that could have been prevented with proper protocols—providing masks for the workers and wet drilling.

Nearly 2,000 people died. The greatest percentage of the dead were African American migrant workers from the South, and in the poem’s haunting image of dust (I think of the phrase when the dust settles), Rukeyser exposes one of the realities of race in America: the disproportionate impact of unhealthy working conditions and environmental pollutants on Black Americans. The image underscores the awful truth of history: even as the specter of death—the great leveler—shrouds them both in whiteness, one of them is more likely to die.

“The poetic image is not a static thing,” she wrote. “It lives in time, as does the poem.” For Rukeyser, a poem’s failure would be that a reader is not brought by the poem beyond it.

How could I not be transported by the world—that place and time—of Rukeyser’s “Book of the Dead” to myriad places beyond it? She could have been writing about the Tuskegee experiment, lead in the water supply in Flint, Michigan, or the impact, across the US, of the COVID-19 pandemic—this moment during which, after all these years, I’ve turned again to her work. This is the prescience, the timeliness and timelessness of Muriel Rukeyser’s poetry.

*

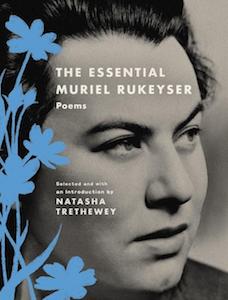

When I agreed to cull 75 poems from her vast body of work—to edit The Essential Muriel Rukeyser—it was the summer of 2019. We were not yet in the midst of a pandemic. I easily recalled that first encounter with her work as a young woman, determined to become a poet, knowing only that something about the time and place I had entered the world, and my particular circumstances, was stirring in me some great need to speak in the language of poetry. And here was a woman poet, born a half century before me, who powerfully embraced her call to bear witness, to tell what she had seen, a poet who, in the aftermath of seeing the beginning of a war, declared—when asked, Where is there a place for poetry?—“Then I began to say what I believe.”

Her words were intoxicating, freeing, and her poems were maps into my as yet unarticulated self: “These are the roads to take when you think of your own country / and interested bring down the maps again… / These roads will take you into your own country… / Here is your road, tying / you to its meanings.”

All those years ago, the introduction to her work guided me in immeasurable ways to my own thinking about poetry. I had been prepared to approach editing this volume as an admirer who would try to pull together a representative sample, its far-reaching themes, forgetting that a compilation such as this one is as much about the moment in which the editor finds herself.

By the time I finally sat down to read her collected works for this anthology, the world was in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, and within the social isolation of that moment, the inevitable separation of our individual lives, came the moral authority and ethical conviction of Rukeyser’s voice, and I could no longer think of the idea of essential in the same way. As a nation, we’d been given a new way to think collectively about what and who was essential. And with the civil unrest and protests against police brutality and social injustice occurring in tandem, the idea of essential had extended to frame a national reckoning around whose lives matter, and how much; whose lives are expendable, and the many ways that the lives of Black people in this country are treated as though they matter less than lives of others. I read again and again these lines:

What three things can never be done?

Forget. Keep silent. Stand alone.

And:

Pay attention to what they tell you to forget

pay attention to what they tell you to forget

pay attention to what they tell you to forget

I saw in them what has always been essential to me about her poems. In a nation steeped in forgetting, in many ways built upon it, Rukeyser, over the course of her long career—a life of conscientious reckoning with the self and the world—would bear witness to many of the most pressing issues of the century with the clarity and moral authority of one whose life was boldly and fully lived. Situating the origins of her poetic vision, she wrote: “War has been in my writing since I began. The first public day that I remember was the False Armistice of 1918.”

We are in a time of crisis. Someone, somewhere, is always in a time of crisis.

That was November, in the midst of the influenza epidemic that would ultimately claim half a million US lives, with a resurgence of the virus as servicemen returned from battle and precautions had lapsed at home. It is sobering to think that day of her first public awareness was also during a pandemic, just as we are in now. And we too are contending with civil unrest, polarization, and divisiveness on a larger scale than we have seen in this nation for some time. Into moments like these a poet’s work emerges that can carry us through the turbulence, a poet whose work can take you into your own country. “In time of crisis,” Rukeyser wrote, “we summon up our strength.”

We are in a time of crisis. Someone, somewhere, is always in a time of crisis.

Rukeyser believed in the essential role of poetry in our lives, “a type of creation in which we may live and which will save us.” Save us because it is a way to feel, to communicate “a form of love.” And we are a nation in need of saving; we are always in need of saving. This is what her poems offer:

And if an essential thing has flown between us,

rare intellectual bird of communication,

let us seize it quickly : let our preference

choose it instead of softer things to screen us

each from the other’s self : muteness or hesitation,

nor petrify live miracle by our indifference.

__________________________________

From the introduction of The Essential Muriel Rukeyser: Poems by Muriel Rukeyser. Copyright © 2021 by Natasha Trethewey. Reprinted courtesy of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Natasha Trethewey

Natasha Trethewey is an American poet who was appointed United States Poet Laureate in 2012 and again in 2014. She won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for her 2006 collection Native Guard, and she is a former Poet Laureate of Mississippi. She is the Board of Trustees Professor of English at Northwestern University.