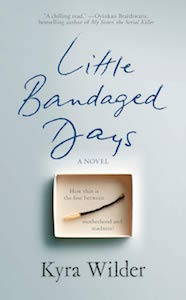

On the Relationship Between Motherhood and Madness in Victorian Literature

Kyra Wilder Talks About the Voice in Her Head

When it was time to pick a topic for my master’s thesis, I was also working and pregnant with my second child. So when I decided to write about the disturbing, stressed-out mothers you sometimes find in books written by Victorian women, you could say that I came by the topic honestly.

I had been pregnant twice during the course of the two-year program. I thought, won’t looking at the larger social implications of these sort-of crazy, definitely scary moms be kind of funny and also fun? Like, Ha! I’m a little bit crazy too!

And then I had my second baby and he cried without stopping for a year.

He was just shy of 11 pounds when he was born and needed extra time at the hospital because of the way his heart would sometimes start to race. My heart would race too, holding him. We would wait through appointments, our hearts pounding too fast together.

At five weeks old, his vital signs resolved, but he didn’t stop crying. He just didn’t stop crying, and my 18-month-old wasn’t sleeping and I still had my thesis to write.

A distinguishing feature of the crazy moms I was writing about is that they are often cut in half—sometimes literally, such as in sensationally gruesome railway accidents, but psychologically cut to ribbons will do too, in a pinch. At any rate, there’s doubling and splitting and tearing apart; demure beauty and disfiguring rage, like a coin flipped high in the air, spinning out to a blur.

When my crying baby was three months old we moved into a small apartment in New York City. Sometimes people would stop me on the street to tell me he was crying, and I would smile at them and pretend that I was dead. His soft baby hair fell out in little patches and sometimes mine did too. Something was there, something was happening between the two of us.

At first my crying baby’s doctors told me it was colic, and then they told me it was his teeth. One night, staying up with him, a nerve lit up in my face. I got an emergency appointment and a dentist told me there was a problem with my teeth. Within hours I was having the inside of my mouth re-planed. All my molars filed down flat. Something was happening between us.

He started getting high fevers, and I broke out in a hot rash. His fevers spiked, and the rash crept down my arms and legs and across my chest. We accompanied each other to appointments. He got medicine and I got cortisone injections; we soaked together in oatmeal baths. I got Bell’s palsy and had trouble for a while working one side of my face.

If you asked me if the book I wrote about a mother who is alone in a small apartment with two young children, who is trying her best but who is losing her mind, is based on my own experience, my answer would be yes.

It’s motherhood itself, not children, that seems to drive the women I was writing about mad. There was the mysterious Lady Audley from Lady Audley’s Secret, with her delicate features and bewitching golden hair. By all accounts a perfect lady, except for when she wasn’t, and people seemed to wind up dead. We find out that she’s at least the third in a line of women who all seemed perfectly lovely, up until the moment they gave birth. Then there’s the tragic Lady Isabel of East Lynne who returns home in secret, having been disfigured in an accident, to care for her own children as their long-suffering governess. No one can love her children like Lady Isabel, and even she can only love them as a hollow, limping ghost.

I was trying to write analytically about the way these textual pregnancies functioned as some kind of witchy tripwire. But the project was getting to be less charming than it had seemed at first. My tongue-in-cheek analysis of these fictional women and their dangerous mothering was less cute, maybe, when viewed from inside my own newly drooping face.

He kept crying and I kept writing and revising. We sat together and tried to puzzle an argument out. He would be quiet for a while when I nursed him. But when nursing him, it was hard to think. I had to have him propped the right way on a pillow so that I could type and flip pages in my books while keeping my body underneath him very still. I got notes back from my advisors and tried to work them in without moving. I tried to imagine a way I could push keys more quietly. Flip pages without flipping them. Write without writing. Doubling and dividing, mothering and going mad, Lady Isabel, Lady Audley, and also, maybe me.

I had an accident in the apartment, something to do with my head. I can’t remember. I was holding him, and he was crying, and then I had an accident, and I was concussed. Recovering, running by the East River there was an accident with his jogging stroller, the wheel crumpled underneath it and he was flipped into the concrete. He’d been buckled in tight, but still. But still. There was blood.

Someone I didn’t know and can’t remember helped me carry him and his brother home. My older son was fine, but my crying baby was concussed. Blood in the ear and a dead tooth. And I’d only just the other day said that all his crying made my ears bleed. There were repercussions, it seemed, new rules, punishments I didn’t understand. I was beginning to suspect myself.

We rode out our concussions in our small apartment together. We rubbed our gums and licked our damaged teeth. If we were doubling each other or if we were each splitting in half, I couldn’t tell. There was something happening between us that I couldn’t understand. When I slept, I dreamed that he wasn’t my baby, that I was some other mother, or sometimes that one or both of us was dead and didn’t know it yet.

Then one winter, up in the snow on a perfect day, watching the boy that had been my crying baby learn to ski in the French Alps, I started hearing a voice in my head.

If you asked me if the book I wrote about a mother who is alone in a small apartment with two young children, who is trying her best but who is losing her mind, is based on my own experience, my answer would be yes. I would say yes, but that this woman, this other mother, isn’t me.

Because I was fine. I was fine in the end and my babies were fine too. My crying baby got older and stopped crying and I finished my thesis. We moved to New Jersey and then to Switzerland. But I wondered about that year. I tried not to, but I did.

Then one winter, up in the snow on a perfect day, watching the boy that had been my crying baby learn to ski in the French Alps, I started hearing a voice in my head. A woman who kept talking and couldn’t stop.

Maybe she was talking to me because I had been fine. And I’d been fine because I’d had help. I’d had friends. A running partner who would meet me before the sun came up and we would glide along the path by the East River or through Central Park. A friend who made me the best mugs of tea. I had friends to meet for bagel playdates. Friends who told me my crying baby was so cute. Friends to order take-out with when it was too hot to cook. Evenings where we would bathe all our babies in the same tub and carry them home dozing in borrowed pajamas. I have a husband, too, who is better than me at rocking crying babies, who got up early to take care of them and stayed up late.

Her voice got to be so clear though—Erika’s, this other woman’s. I started writing down some of the things she said. She was deep in a place after all that I had been to, but she didn’t have the people I’d had to pull her out.

I made notes pushing strollers, and while I was cooking. I jotted down sentences riding trams around the city and taking the kids to parks. But I didn’t really start writing until one morning, running in the woods along the French border, I hurt my knee and suddenly it was hard to leave the house.

Stuck in a chair, trying not to move my leg, I was brought back to where I had been with my crying baby in New York, but I was far enough away from that year that I could think. I gave Erika the apartment we had when we first came to Geneva. I took her to the park I used to sit at, the one with the sandbox and the water pump. I watched her ride the trams that I had ridden. I let her cook the dinners I liked to cook. After ten months I still couldn’t run, but I had pages and pages of words in Erika’s voice.

I booked a tiny room in a hotel in London near King’s Cross, the kind where the carpets sag underneath your feet and you’re pretty sure if there’s a fire, you’ll go up in smoke. For five days I hardly left. I covered the walls in post-it’s and apologized to the hotel staff. I thought about Erika and Geneva and New York and my thesis and my crying baby and I wrote. When I flew back to Geneva I had a book.

I was lucky. I was very lucky. People have said that Little Bandaged Days is a dark book, and it is, of course. In its own way, though, I like to think of it as a (yes, kind of messed up) love letter to my friends. My own kind of thank you to the amazing women who listened to me and made me laugh, who made it possible for me to write this book instead of live inside some version of it, who made it possible for me to be a mother without going (completely) mad.

_______________________________________________________

Little Bandaged Days is available now via Abrams Books.

Kyra Wilder

Kyra Wilder received her BA and MA in English Literature at San Francisco State University, where she then worked under Michael Tusk at the Michelin-starred Quince, making pasta. She continued working in restaurants in New York, before moving with her family to Switzerland, where she is now based. Little Bandaged Days is her first novel.