On the Radical Afterlives of William Wordsworth

A Poet Who Inspired a Generation of Naturalists and Artists

“Poetry makes nothing happen,” wrote W. H. Auden in his poem on the death of fellow poet W. B. Yeats. He was wrong. Sometimes poetry can change the world.

William Wordsworth was not merely the most admired English poet of the 19th century: his poetry made many things happen. Locally, the ecology and economy of the vale of Grasmere, and the wider Lake District, were changed as a result of his canonization. Nationally, he made new claims for the power of poetry that shaped the minds of the most influential thinkers in Victorian Britain. Globally, his influence extended to John Muir’s passion for the preservation of Yosemite.

Auden did not in fact believe that poetry makes nothing happen. Poets often disagree with themselves, which is one of the things that makes them poets. Having said that poetry makes nothing happen, he went on, later in the same poem, to describe poetry as “A way of happening, a mouth.”

Wordsworth’s poetry was a way of happening because of the new way in which he sought, as Keats put it, to “think into the human heart” by means of an unprecedented examination of the development of his own mind and his sense of belonging in the world. He became the mouth of his generation for what Keats called “the true voice of feeling.”

In Victorian England, and simultaneously in the young United States of America, Wordsworth came to be regarded as a central figure in the revolutionary shift in cultural attitudes that would eventually be called the Romantic movement. He and his fellow poets and philosophers changed forever the way we think about childhood, about the sense of the self, about the purpose of poetry, and especially about our connection to our surroundings.

Hazlitt believed that Wordsworth and Coleridge embodied the spirit of the age. Their imaginative cross-fertilization made them into, to adapt a phrase of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s, a composite “representative man.” Among the “great men” of his own time, Emerson regarded Napoleon as the archetypal “man of the world,” the “representative of the popular external life and aims of the 19th century,” and Goethe as the philosopher of the “multiplicity” of its inner life.

Out of Wordsworth comes a manifesto for the enduring value of poetry beyond even that of religion, philosophy and science.

Yet Emerson’s own capacious mind and his vision for American literature were shaped less by Goethe than by the poetry of Wordsworth and the ideas of Coleridge. The composite Wordsworthian–Coleridgean identity began to fracture on that morning of Saturday, December 27th, 1806 when Coleridge saw, or thought he saw, Wordsworth in bed with Sara Hutchinson.

It broke down almost irretrievably after Basil Montagu passed on the gossip about Wordsworth finding Coleridge impossible to live with because of the alcohol and the opium. Though Coleridge would be generous in writing of Wordsworth’s gifts in Biographia Literaria, and Wordsworth would mourn Coleridge’s passing in the “Extempore Effusion on the Death of James Hogg,” it would never be glad confident morning again.

As he settled into fame and a gentleman’s life at Rydal Mount, Wordsworth’s genius deserted him. Yet as his mortal powers waned, he began to achieve immortality: his spirit lived on by means of his inspiration upon the next generation of readers and writers, then far beyond. To use another phrase of W. H. Auden’s in his elegy on the death of W. B. Yeats, Wordsworth became his admirers.

Radical Wordsworth endured through the 19th century in the poetry of Keats and Shelley, John Clare and Felicia Hemans (and, by negative influence, Byron); in the art of Benjamin Robert Haydon and the prose of Thomas De Quincey, William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb; in the ideas of John Stuart Mill, Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin and George Eliot; in the deeds of Canon Rawnsley, Stopford Brooke and Beatrix Potter; and, across the Atlantic, in the visions of Emerson, Thoreau and John Muir.

Radical Wordsworth survives today whenever a person walks for pleasure and takes spiritual refreshment in the mountains or when a heart leaps up at the sight of a rainbow in the sky or a tuft of primroses in flower.

*

Thirty years after Wordsworth’s death, and twenty after the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Matthew Arnold recognized which way the wind had blown. Introducing an anthology of The English Poets, he argued, under the deep influence of Wordsworth, that the future spirit of humankind would depend on poetry. Religion had relied on supposed fact; the science of Lyell, Darwin and others had disproved those facts.

The only part of religion to endure would be “its unconscious poetry.” More and more, society would “have to turn to poetry to interpret life for us, to console us, to sustain us”: “Most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry.” Even science itself would appear incomplete without it, “For finely and truly does Wordsworth call poetry ‘the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all science’; and what is a countenance without its expression?”

Arnold’s prose then takes off from another phrase in the preface to Lyrical Ballads:

Again, Wordsworth finely and truly calls poetry “the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge”; our religion, parading evidences such as those on which the popular mind relies now; our philosophy, pluming itself on its reasonings about causation and finite and infinite being; what are they but the shadows and dreams and false shows of knowledge?

The day will come when we shall wonder at ourselves for having trusted to them, for having taken them seriously; and the more we perceive their hollowness, the more we shall prize “the breath and finer spirit of knowledge” offered to us by poetry . . . the best poetry will be found to have a power of forming, sustaining, and delighting us, as nothing else can.

Out of Wordsworth comes a manifesto for the enduring value of poetry beyond even that of religion, philosophy and science. There was an unprecedented market for biography in the Victorian era. A notably popular series of literary lives, published by Macmillan under the editorship of the prolific journalist- politician-bookman John Morley, was called “English Men of Letters.”

The volume on Wordsworth was published in 1881, the year after Arnold’s essay on the importance of poetry. It made the startling claim that “the maxims of Wordsworth’s form of natural religion were uttered before Wordsworth only in the sense in which the maxims of Christianity were uttered before Christ”:

The essential spirit of the Lines near Tintern Abbey was for practical purposes as new to mankind as the essential spirit of the Sermon on the Mount. Not the isolated expression of moral ideas, but their fusion into a whole in one memorable personality, is that which connects them for ever with a single name. Therefore it is that Wordsworth is venerated; because to so many men—indifferent, it may be, to literary or poetical effects, as such—he has shown by the subtle intensity of his own emotion how the contemplation of Nature can be made a revealing agency, like Love or Prayer,—an opening, if indeed there be any opening, into the transcendent world.

Thirty years after his death, the poet from an obscure nook of northern England, who in the first half of his life was mercilessly derided by the critics, was being compared to Jesus Christ.

The author of the book that made this comparison was Frederic William Henry Myers. The son of a Keswick clergyman who knew and revered Wordsworth, Myers was a bisexual ex-don from Cambridge who, like Matthew Arnold, had become an inspector of schools. A few years before writing the biography, he was deeply scarred by the gruesome suicide in the Lake District of his cousin’s wife Annie Marshall, with whom he had fallen in love and was having a (very intense but almost certainly unconsummated) affair.

He had also been deeply affected by the novels of George Eliot, herself another Victorian sage with boundless admiration for Wordsworth. After reading the final instalment of Middlemarch in the late autumn of 1872, Myers wrote Eliot a long fan letter in which he especially singled out the “noble lovemaking” of Ladislaw and Dorothea. The “contact of noble souls,” he suggested, was the only reason to go on living in a world where “there is no longer any God or any hereafter or anything in particular to aim at.”

The following spring, Eliot visited Myers in Cambridge. On a rainy May day, they walked in the Fellows’ Garden of Trinity College. She responded to the three negatives in his letter—no God, no hereafter, no earthly goal—in words that seemed to Myers positively oracular: “taking as her text the three words which have been used so often as the inspiring trumpet-calls of men,—the words God, Immortality, Duty,—pronounced, with terrible earnestness, how inconceivable was the first, how unbelievable the second, and yet how peremptory and absolute the third. Never, perhaps, have sterner accents affirmed the sovereignty of impersonal and unrecompensing Law.”

The poet from an obscure nook of northern England, who in the first half of his life was mercilessly derided by the critics, was being compared to Jesus Christ.

Myers published his account of this conversation in the same year as his biography of Wordsworth. In reflecting on the necessity of Duty and the unbelievability of Immortality, he would inevitably have turned his mind to the two odes that dominated the Poems of 1807. Neither Eliot nor Myers could believe in God: the findings of Lyell in geology, popularized in Robert Chambers’ 1844 Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, had cracked centuries of Creationist belief. And then there was Darwin.

Yet Myers could not live without maintaining faith in some kind of spiritual realm. He had to believe in the possibility that he might one day be reconnected with Annie on, to use the words of the “Intimations” ode, the shore of an “immortal sea.” In his study of Wordsworth, he kept returning to those passages which hinted at some “mystic relation” between the visible and the invisible world. That was why he wrote of Wordsworth’s natural religion offering “an opening, if indeed there be any opening, into the transcendent world.”

In the circumstances, it was almost inevitable that, like many late Victorians grappling with death in an age of uncertainty, Myers became interested in spiritualism. Two years after the publication of his biography of Wordsworth, he became one of the founding members of the Society for Psychical Research. He began visiting mediums, writing about apparitions, and engaging in research on clairvoyance and transmundane experience.

He spent his later years developing a theory of the “subliminal self” or “subliminal consciousness,” suggesting that paranormal and mystical events were the product of contact between the realm of the deep unconscious and what he called the “metetherial world.” To describe these mysterious forms of contact, he coined a new word: “telepathy.”

Myers invoked Wordsworth as prime evidence for his theory. Turning to The Prelude, he found numerous instances of “subliminal uprush”—those spots of time in which “the light of sense / Goes out, but with a flash that has revealed / The invisible world.” Lines such as “To hold fit converse with the spiritual world” convinced him that there was a “telaesthetic” quality to Wordsworth’s genius.

The poems’ moments of heightened consciousness “bring with them indefinite intimations of what I hold to be the great truth that the human spirit is essentially capable of a deeper than sensorial perception, of a direct knowledge of facts of the universe outside the range of any specialized organ or any planetary view.”

The word “intimations” is a sign that he was thinking of the great ode and its hope that, contrary to the gloomy pronouncement of George Eliot, there was a form of immortality that allowed the human spirit to survive beyond bodily death.

__________________________________

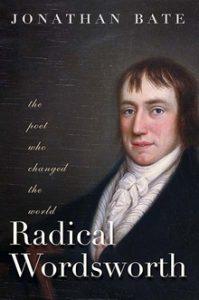

Adapted from Radical Wordsworth: The Poet Who Changed the World, by Jonathan Bate, published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Jonathan Bate

Sir Jonathan Bate is Foundation Professor of Environmental Humanities at Arizona State University and a senior research fellow at Oxford University, where he was formerly provost of Worcester College.