On the Power of Afrofuturism in the 21st Century

Tim Fielder Details the Legacies of Radical Black Imaginaries

Every art form has an economy that surrounds and fuels its standing within the world’s cultural systems. The very survival of many industries is absolutely dependent upon the products generated by those forms as artisans of industry utilize their tools to design, manufacture, distribute, and market to willing consumers. Corporations have long employed the imaginations of futurists (those who forecast the trends in economics, business, government, and technology) to project trends and themes so that crucial investment decisions can be made to maximize profit. Imagine the shock and horror of the world’s oligarchs, who pay millions to professional futurists, when Marvel Studios’ “Black Panther” made $1.3 billion at the box office. A desire was present, an intent formed, a product provided; gold was the result. No one saw it coming. Except those who practice Afrofuturism.

Afrofuturism. We’ve heard that word used more and more over the last several years. The field lies at the intersection of culture, technology, speculative fiction, socioeconomics, and racial politics. Although the word is a recent creation, the practice of generating artifacts within the field itself goes back centuries. For me, it began in my childhood among the cotton fields of the Mississippi Delta.

In my household, we celebrated the odd and the nerdish: DC, Marvel, Heavy Metal, fandom, science fiction, fantasy. My specific love was an illogical adoration for all things Star Wars. The miracle was that my parents, both born and raised amongst the first generation of Mississippi born college bound African Americans, allowed my siblings and me to experiment in our aspirations.

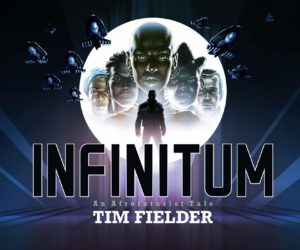

This grew into a love for generating my own science fiction tales featuring black characters, and the result—my new graphic novel, INFINITUM: An Afrofuturist Tale—will arrive to the world in January of 2021. Then, it will join other elements of what I call the Afrofuturist economy. Also within that economy: Marvel’s Black Panther, Octavia Butler’s Kindred, George Clinton’s Parliament Funkadeclic, Jordan Peele’s Get Out, Janelle Monae’s Dirty Computer, Ruth Carter’s Afrocentric fashion designs, Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone, HBO’s Lovecraft Country, Rasheedah Phillips’ expansive housing policy, Samuel Delany’s groundbreaking novel Nova, and Nalo Hopkinson’s The Midnight Robber.

Until scholar Mark Dery coined the term “Afrofuturism” in the 1990s, we simply called it “black sci-fi.” Since the late 90s, a vibrant academic base has worked on Afrofuturist work, including scholars such as Alondra Nelson. Afrofuturism as a practice can look backwards in time, at our present, and into the future; there are many different modes of Afrofuturism that can connect with fields as varied as politics and, yes, even trend projection.

Afrofuturism lies at the intersection of culture, technology, speculative fiction, socioeconomics, and racial politics.

Over the last few years, the Afrofuturism mantle has expanded with Reynaldo Anderson’s Black Speculative Arts Movement, drawing practitioners both young and old. More recently, the field has garnered financial and critical acclaim within our contemporary media space. Just within the last few months, UNESCO sponsored an online summit in which 30 of the most dynamic Afrofuturists, myself included, met to project the future of Black America.

Of course, Afrofuturism expands well beyond America to the diasporic and back to the African continent itself, the objective of practitioners being to define the practice and utilize its power to make the world a better place. If one can hold, hear, feel, and see our work, it all adds to the economic power of Afrofuturism.

My specific skill set resides within the area of visual Afrofuturism with a focus on sequential narratives, also known as comics or graphic novels. Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics was the gamechanger in showcasing the language and history of comics as an art form. Initially treated as disposable commodities printed on cheap paper, graphic novels are the more sophisticated variants of comics, featuring longer and more immersive stories with energetic art styles. In the last few years, comics have proven themselves to be the core of our robust streaming and cinematic content creation industry. The bottom line: sequential storytelling is able to attain an economically viable price point without the potentially devastating economic risk.

*

INFINITUM examines the life of an African warlord, Aja Oba, who is cursed with the gift of immortality. This adventure story propels the reader through the far-flung past, into the volatile present, towards the distant future on a path of dramatic redemption. It was my intent to produce a book that would satisfy in the written narrative as well as the visual narrative. Fully rendered painted vistas would co-exist with characters of color who had epic storylines. My comrades in visual Afrofuturism, such as John Jennings’ Abrams imprint Megascope and many long-established black indie creators, also moved the idea forward. At the core of INFINITUM, I wanted to visually show Black people being their most regal, benign, malevolent, intelligent, and ultimately, human. There’s a market and audience for that.

Not so very long ago, such narratives would not exist, or at the very least, not have broken through the cultural zeitgeist. Why now? Why do these projects exist? I was told by fellow Afrofuturist Ytasha Womack, author of Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture: “The world wants to see stories of Black people in speculative scenarios, and the thirst is insatiable.’ I agree fully.

Afrofuturism as a practice can look backwards in time, at our present, and into the future; there are many different modes of Afrofuturism that can connect with fields as varied as politics and, yes, even trend projection.

I believe that there are forces that seek to aggressively exploit the viability of Afrofuturism within the near future. I am perfectly fine with that. How long will it last? Like hip-hop, bebop, and blaxploitation movies, longevity in content entirely depends on the innovation of the creators, quality of the content, financial backing of business ventures big and small, and the ultimate arbiter: interest from the audience.

As a middle aged African American male, my thoughts as of late have turned towards my legacy. One looks back and says, what have I done to contribute to world culture? Will I be remembered? I am enthusiastic about showing my work to the world; I feel that the world has caught up to my ideas. My dream would be that as a visual Afrofuturist, my work would be held in at least equal light to the generations of prose writers, in part to continue establishing an Afrofuturist economy. We are facing an inflection point at which Afrofuturism can change society, as it now has the cultural reach powered by intellectual rigor and economic power.

My editor, Tracy Sherrod, asked me during a work session why the main character in INFINITUM suffers. My reply was simple and direct: “We are not meant to live forever. We are meant to decay and rot, providing sustenance to those that come after us.”

__________________________________

Infinitum: An Afrofuturist Tale by Tim Fielder is available now via Amistad Press.

Tim Fielder

Tim Fielder is an illustrator, cartoonist, animator and OG Afrofuturist. He is the founder of Dieselfunk Studios, an intermedia storytelling company, and is an educator for institutions such as the New York Film Academy and Howard University. Tim has served clients such as Marvel, Tri-Star Pictures, Ubisoft Entertainment, and the Village Voice, and is known for his TEDx Talk on Afrofuturism. He won the prestigious 2018 Glyph Award, and his work has been showcased in the Hammonds House Museum, Exit Art and NYU Gallatin Gallery. He lives in New York City.