At that age there’s music playing in your head all the time, as if a radio were transmitting from the nape of your neck, inside your skull. Then one day that music starts to grow softer, or it just stops. When that happens, you’re no longer a teenager. But we weren’t there yet, not even close, back when we talked to the dead. Back then, the music was at full blast and it sounded like Slayer, Reign in Blood.

We started with the Ouija board at the Polack’s house, locked in her room. We had to do it in secret because Mara, the Polack’s sister, was afraid of ghosts and spirits. She was afraid of everything—man, she was a stupid little kid. And we had to do it during the day, because of the sister in question and because the Polack had a big family and they all went to bed early, and the whole Ouija board thing didn’t go over well with any of them because they were crazy Catholic, the kind who went to mass and prayed the rosary. The only cool one in that family was the Polack, and she had gotten her hands on a tremendous Ouija board that came as a special offer with this magazine on magic, witchcraft, and inexplicable events that was part of a series called The World of the Occult; they sold them at newspaper kiosks and you could collect and bind them. Several issues had already had promotions for Ouija boards, but they always ran out before any of us could save the money to buy one. Until the Polack started to take the thing seriously and really tightened her belt, and then there we were with our lovely board, with its numbers and letters in gray, a red background, and some very satanic and mystical drawings all around the central circle.

It was always the five of us who met: me, Julita, Pinocchia (we called her that because she was thick as wood, the slowest in the whole school, not because she had a big nose), the Polack, and Nadia. All five of us smoked, so the planchette seemed to be floating on fog as we played, and we left a terrible stench in the room the Polack shared with her sister. Plus, it was winter when we started with the Ouija board, and we couldn’t even open the windows because we’d freeze our asses off.

And that was how the Polack’s mother found us: shut in with all the smoke and the planchette going all kinds of crazy. She kicked us all out. I managed to salvage the board—it stayed with me after that—and Julita kept the planchette from breaking, which would have been a disaster for the poor Polack and her family, because the dead guy we were talking to right then seemed really evil. He’d even said he wasn’t a dead spirit, but a fallen angel. Still, by that point we knew that spirits are some crafty liars and we didn’t get scared anymore by their cheap tricks, like guessing birthdays or grandparents’ middle names. All five of us pricked our fingers with a needle and swore with blood that we didn’t move the planchette, and I believed it was true. I know I didn’t. I never moved it, and I really believe my friends didn’t either. It was always hard for the planchette to start moving at first, but once it got going it seemed like there was a magnet connecting it to our fingers. We barely even had to touch it, we never pushed it, not even a nudge; it slid over the mystical drawings and the letters so fast that sometimes we didn’t even have time to jot down the answers to the questions (one of us always took notes) in the special notebook we kept for just that purpose.

When the Polack’s crazy mom caught us (and accused us of being satanists and whores, and called all our parents: it was a clusterfuck), we had to stop the game for a while, because it was hard to find another place where we could keep going. At my house, impossible: my mom was sick in those days and she didn’t want anyone in the house. She could barely stand my grandmother and me, and she would straight up kill me if I brought friends home. Julita’s was no good because the apartment where she lived with her grandparents and her little brother had only one room, which they divided with a wardrobe to make two rooms, kind of. But it was just that space, no privacy at all, otherwise just the kitchen and bathroom, plus a little balcony full of aloe vera and crown-of-thorns plants—impossible any way you looked at it. Nadia’s place was also impossible because it was in the slum: the other four of us didn’t exactly live in fancy neighborhoods, but no chance in hell would our parents let us spend the night in a slum, they would never go for that. We could have snuck around and done it without telling them, but the truth is we were also a little scared to go. Plus, Nadia didn’t bullshit us: she told us it was really rough where she lived, and she wanted to get the hell out of there as soon as she could, because she’d had it with hearing the gunshots at night and the shouts of the drunk gauchos, and with people being too scared to come visit her.

So we were left with Pinocchia’s place. The only problem with her house was that it was really far away, we’d have to take two buses, plus convince our parents to let us go all the way out to East Bumfuck. But we managed it. Pinocchia’s parents pretty much left her alone, so at her house there was no risk of getting kicked out with a lecture on God. And Pinocchia had her own room, because her siblings had already left home.

So finally, one summer night, all four of us got permission and went to Pinocchia’s house. It was really far, her house was on a street that wasn’t even paved, with a ditch running alongside it. It took us like two hours to get there. But when we did, we realized right away that it was the best idea in the world to make the trek all the way out there. Pinocchia’s room was really big, with a double bed plus bunk beds: all five of us could sleep there, easy. It was an ugly house because it was still under construction: unpainted plaster, lightbulbs hanging from ugly black cords, no lamps, and a bare cement floor, no tile or wood or anything. But it was really big, with a terrace and a barbecue pit, and it was much better than any of our houses. It sucked to live so far away, sure, but if it meant having a house like that—even an unfinished one—it was worth it. Out there, far from the center of Buenos Aires, the night sky looked navy blue, there were fireflies, and the smell was different, like a mixture of burnt grass and river. Pinocchia’s house had bars on all the windows, it’s true, and it also had a giant black dog guarding it. I think it was a rottweiler, and you couldn’t play with it because it was so mean. It seemed that living far away had its dangers too, but Pinocchia never complained.

Maybe it was because the place was so different—because that night in Pinocchia’s house we did feel different, with her parents listening to Los Redondos and drinking beer while the dog barked at shadows—that Julita got up the nerve to tell us exactly which dead people she wanted to talk to.

Julita wanted to talk to her mom and dad.

*

It was really good that Julita finally spoke up about her folks, because we could never bring ourselves to ask. At school people talked about it a lot, but no one ever said a thing to her face, and we jumped to her defense if anyone came out with any bullshit. The thing was that everyone knew Julita’s parents hadn’t died in any accident: Julita’s folks had disappeared. They were disappeared. They’d been disappeared. We didn’t really know the right way to say it. Julita said they’d been taken away, because that’s how her grandparents talked. They’d been taken away, and luckily the kids had been left in the bedroom (no one had checked the bedroom, maybe: anyway, Julita and her brother didn’t remember anything, not of that night or of their parents either).

Julita wanted to find them with the board, or ask some other spirit if they’d seen them. She wanted to talk to them, and she also wanted to know where their bodies were. Because that question drove her grandparents crazy, she said; her grandma cried every day because she had nowhere to bring flowers to. Plus, Julita was really something else: she said that if we found the bodies, if the dead told us where they were and it turned out to be really real, we’d have to go on TV or to the newspapers, and we’d be famous and everyone in the world would love us.

To me, at least, Julita’s cold-bloodedness seemed really harsh, but I thought, Whatever, let Julita do her thing. What we for sure had to start doing, she told us, was coming up with other disappeared people we knew, so they could help us. In a book on how to use the board, we’d read that it helped to concentrate on a dead person you knew, to recall their smell, their clothes, their mannerisms, their hair color, construct a mental image, and then it would be easier for the dead person to really come. Because sometimes a lot of false spirits would turn up and lie to you and go around and around in circles. It was hard to tell the difference.

It was really good that Julita finally spoke up about her folks, because we could never bring ourselves to ask.The Polack said that her aunt’s boyfriend was disappeared, that he’d been taken during the World Cup. We were all surprised because the Polack’s family was really uppity. She explained that they almost never talked about the subject, but her aunt had told her once in confidence, when she was a little drunk after a barbecue at her house. The men were getting all nostalgic about Kempes and the World Cup, and the aunt got pissed off, downed her red wine, and told the Polack all about her boyfriend and how scared she’d been. Nadia contributed a friend of her dad’s who used to come for dinner on Sundays when she was little, and one day had just stopped coming. She hadn’t really noticed that friend’s absence, mostly because he used to go to the field a lot with her dad and brothers, and they didn’t take her to games. But her brothers noticed it more when he didn’t come around, and they asked their old man, and the old man couldn’t bring himself to lie to them and say they’d had a fight or something. He told the boys that the friend had been taken away, same thing Julita’s grandparents said. Later, Nadia’s brothers told her. At the time, neither the boys nor Nadia had any idea where he’d been taken, or if being taken away was common, or if it was good or bad. But now we all knew about those things, after we saw the movie Night of the Pencils (which made us bawl our eyes out; we rented it about once a month) and after the Nunca Más report on the disappeared—which Pinocchia had brought to school, because in her house they let her read it. Plus there was all the stuff we read in magazines and saw on TV. I contributed with our neighbor in back, a guy who’d lived there only a short time, less than a year. He didn’t go out much but we could see him moving around out the back windows, in his little backyard. I didn’t remember him much, it was kind of like a dream, and it wasn’t like he spent a lot of time in the yard. But one night they came for him, and my mom told everyone about it, and she said that thanks to that son of a bitch they could have easily taken us too. Maybe because she repeated it so much, the thing with the neighbor stuck with me, and I couldn’t relax until another family moved into that house and I knew he wasn’t ever going to come back.

Pinocchia didn’t have anyone to contribute, but we decided we had enough disappeared dead for our purposes. That night we played until four in the morning, and by then we were starting to yawn and our throats were getting scratchy from so much smoking, and the most fantastic thing of all was that Pinocchia’s parents didn’t even come knock on the door to send us to bed. I think—I’m not sure, because the Ouija consumed my full attention—that they were watching TV or listening to music until dawn, too.

*

After that first night, we got permission to go to Pinocchia’s house two more times that same month. It was incredible, but all our parents or guardians had talked on the phone with Pinocchia’s parents, and for some reason the conversation left them totally reassured. But we had a different problem: we were having trouble talking to the particular dead people we wanted—that is, Julita’s parents. We talked to some spirits, but they gave us the runaround, they couldn’t make up their minds yes or no, and they always stopped at the same place: they’d tell us where they’d been captured, but then they wouldn’t go any further, they couldn’t tell us if they’d been killed there or if they’d been taken somewhere else. They’d talk in circles, and then they’d leave. It was frustrating. I think we talked to my neighbor, and he got as far as naming the detention center Pozo de Arana, but then he left. It was him, for sure: he told us his name, we looked him up in Nunca Más, and there he was, on the list. We were scared shitless: it was the first certified for-real dead guy we’d talked to. But as for Julita’s parents, nothing.

It was our fourth time at Pinocchia’s when what happened happened. We’d managed to communicate with someone who knew the Polack’s aunt’s boyfriend; they’d gone to school together, he said. The dead guy we were talking to was named Andrés, and his story was that he hadn’t been taken away and he hadn’t disappeared: he’d escaped on his own to Mexico, and he died there later in a car accident, totally unrelated. Well, this Andrés guy was cool, and we asked him why all the dead people took off as soon as we asked them where their bodies were. He told us that some of them left because they didn’t know where they were, and they got nervous, uncomfortable. But others didn’t answer because someone bothered them. One of us. We wanted to know why, and he told us he didn’t know the reason, but that was the deal, one of us didn’t belong.

Then the spirit left.

We sat for a beat thinking about what he’d said, but we decided not to give it too much importance. At first, when we’d started playing with the board, we always asked the spirit that came if any of us bothered it. But then we stopped doing that because the spirits loved to run with the question, and they’d play with us. First they’d say Nadia, then they’d say no, everything was cool with Nadia, the one who bothered them was Julita, and they could keep us going all night, telling one of us to put our fingers on the planchette or take them off, or even to leave the room, because those fuckers would ask us for all kinds of things.

The episode with Andrés left enough of an impression, anyway, that we decided to go over the conversation in the notebook while we cracked open a beer. Then there was a knock at the door. It startled us a little, because Pinocchia’s parents never bugged us.

“Who is it?” asked Pinocchia, and her voice came out a bit shaky. We were all shitting ourselves a little, to tell the truth.

“It’s Leo. Can I come in?”

“Hell yeah!” Pinocchia jumped up and opened the door. Leo was her older brother who lived downtown and only visited their parents on weekends, because he worked every weekday. And he didn’t even come every weekend, because sometimes he was too tired. We knew him because before, when we were little, first and second grade, sometimes he came to pick up Pinocchia at school when their parents couldn’t make it. Then, when we were big enough, we started to take the bus. A shame, because then we stopped seeing Leo, who was really fine, a big dark guy with green eyes and a murderous face, to die for. And that night, at Pinocchia’s house, he was hot as ever. We all sighed a little and tried to hide the board, just so he wouldn’t think we were weird. But he didn’t care.

“Playing Ouija? That thing’s fucked up, I’m scared of it,” he said. “You girls have some balls.” And then he looked at his sister: “Hey, kiddo, can you help me unload some stuff from the truck? It’s for the folks, but Mom already went to bed and Dad’s back is hurting . . .”

“Aw, don’t be a pain in the ass, it’s really late!”

“Well, I could only make it out here just now, what can I say, the time got away from me. Come on, if I leave the stuff in the truck it could get lifted.”

Pinocchia gave a grudging okay and asked us to wait for her. We stayed sitting on the floor around the board, talking in low voices about how cute Leo was, how he must be around twenty-three by now—he was a lot older than us.

Pinocchia was gone a long time, and we thought it was strange, so after half an hour Julita offered to go see what was going on. Then everything happened really fast, almost at the same time. The planchette moved on its own. We’d never seen anything like it. All by itself, really, none of us had a finger on it, not even close. It moved and wrote really quickly, “Ready.” Ready? Ready for what? Just then we heard a scream from the street, or from the front door—it was Pinocchia’s voice. We went running out to see what was going on, and we found her in her mother’s arms, crying, the two of them sitting on the sofa next to the phone table. Just then we didn’t understand a thing, but later, when things calmed down a little—just a little—we more or less put it together. Pinocchia had followed her brother down to the corner.

She didn’t understand why he’d left the truck there when there was plenty of room by the house, but he didn’t answer any of her questions. He’d changed as soon as they left the house, he’d turned mean and wouldn’t talk to her. When they got to the corner he told her to wait, and, according to Pinocchia, he disappeared. It was dark, so it could be that he walked a few steps away and she lost sight of him, but according to her he’d disappeared. She waited a while to see if he would come back, but since the truck wasn’t there either, she got scared. She went back to the house and found her parents awake, in bed. She told them Leo had been there, that he’d been acting really weird, and that he’d asked her to help unload things from his truck. Her parents looked at her like she was crazy. “Leo wasn’t here, sweetie, what are you talking about? He has to work early tomorrow.” Pinocchia started trembling with fear and saying, “It was Leo, it was Leo,” and then her dad got all worked up, and shouted at her and asked if she was high or what. Her mom was calmer, and she said, “Listen, let’s call Leo at home. He’s probably asleep, but we’ll wake him up.” She was doubting a little now too, because she could tell that Pinocchia was really positive and really upset. She called, and after a long time Leo answered, cursing, because he’d been fast asleep. Their mom told him, “I’ll explain later,” or something like that, and she started to soothe Pinocchia, who was having a terrible meltdown.

They even called an ambulance, because Pinocchia couldn’t stop screaming that “the thing” had touched her (an arm around the shoulders, in a sort of hug that had made her feel more cold than warm), and that it had come for her because she was “the one who bothered them.”

Our little group never got together again. Pinocchia was hit really hard, and her parents blamed us.Julita whispered into my ear, “It’s because she didn’t have anyone disappear.” I told her to shut her mouth—poor Pinocchia. I was really scared, too. If it wasn’t Leo, who was it? Because that person who’d come to get Pinocchia looked exactly like her brother, he was like an identical twin, and she hadn’t doubted for a second either. Who was it? I didn’t want to remember his eyes. And I didn’t want to play with the Ouija board ever again, let me tell you, or even go back to Pinocchia’s house at all.

Our little group never got together again. Pinocchia was hit really hard, and her parents blamed us—poor things, they had to blame someone. They said we’d played a mean prank on her, and it was our fault she went a little crazy after that. But we all knew they were wrong; we knew the spirits had come to get her because, as the dead guy Andrés told us, one of us bothered them, and it was her. And just like that, the time when we talked to the dead came to an end.

__________________________________

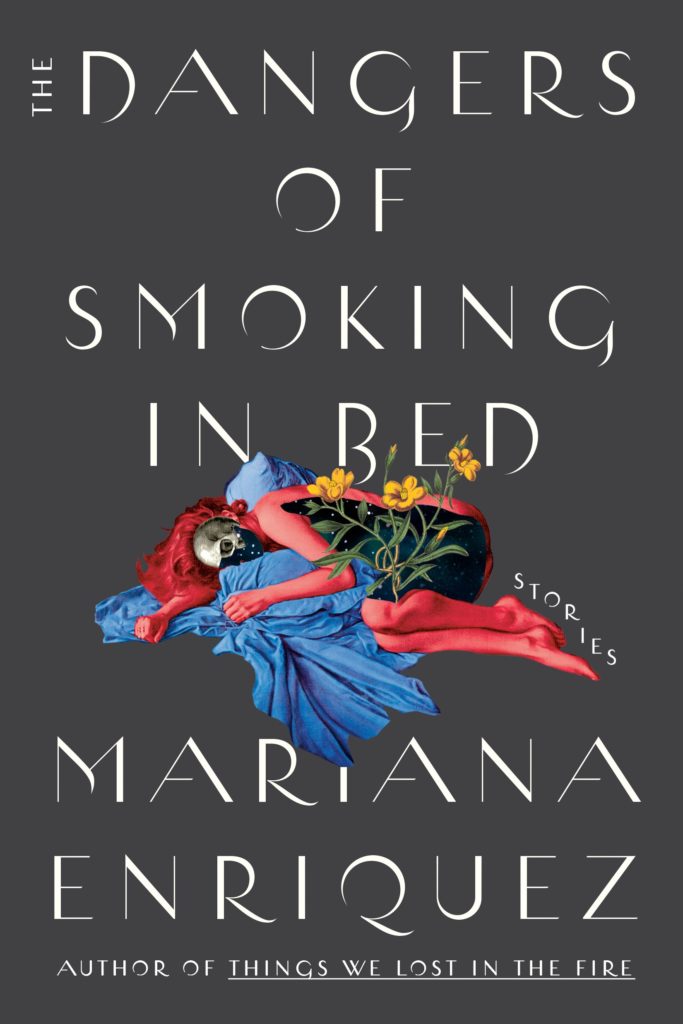

Excerpted from The Dangers of Smoking in Bed: Stories by Mariana Enriquez, translated by Megan McDowell. Excerpted with the permission of Hogarth Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Originally published in Spain as Los peligros de fumar en la cama by Editorial Anagrama in Barcelona, Spain. Copyright © 2017. Translation copyright © 2020 by Penguin Random House LLC.