On the Logistics of Memory; Or, Writing While Uprooted

Anjanette Delgado's Definition of “Home”

Given the choice of dozens of possible places to call home—to start over—I chose Florida. Being of (mostly) sound mind and body, I willingly chose to start over in the state people most love to hate; the punchline of entire late night show episodes, the bane of the country’s existence.

I, too, hate Florida, and I hate it often. Hate its politics, always primed for excess. The relentless humidity. Living in fear of one major hurricane or another six months out of every year. Mostly, I hate its flatness. Mile after mile of it: flat county after flat county, not a hill in sight.

But. I also love Florida. Love being able to find Cuban coffee, Argentinian empanadas, and Haitian griot without much effort, minutes from my home in Miami’s “Sabuesera” (the Latinized word for the city’s mostly Latinx Southwest). And I love that I get to hear so many voices. All around me, people speak with different singsongs, like a rosary of assorted beads, a prayer composed of mixed whisperings: Puerto Rican, Colombian, Peruvian, Salvadoran, Dominican, Cuban. More to the North and East: Haitian, and also some Polish, Italian, Romanian. More to the south, a scattering of Senegalese, South African, Indian.

And then there is the tension for which the writer in me is so grateful. It’s everywhere, in every inch of this place. The heat always making something simmer between past and present, between more and less, the now and the then constantly threatening to boil over; the conflict between “us” and “them” so sharp and so present in daily life that in 2008, the state had to change its state song because the original one was just too racist. For Florida.

And yet the biggest source of tension here, I find, incredibly, isn’t race. It’s the tension between “here” and “there.” Most of the people who live here are uprooted beings: uprooted by old age, by their own health, by a nearby dictator’s overreach, by hunger, by climate change, by disaster, by heartbreak. I know all this, and still, I was surprised to realize, just a few months ago, while editing an anthology on Florida’s literature of uprootedness, that I, myself, am not home. Decades after landing here, I am still moved by what I left.

I will never again be home because home is a construction of a certain place, at a certain time.

Tracing my own work in both languages, I am shocked to see this is the common thread most present in it, though I have refused to see it: my own displacement of the mind, of the heart. I describe this dynamic in Home in Florida: Latinx Writers and the Literature of Uprootedness:

We might draw two points (on the spectrum of displacement). One, located at the start, on the left side of what will be an uneven line, holds your recently uprooted: the soon-to-returns, the just-arriveds, the what-have-I-dones, souls with turmoil tattooed in indigo on the whites of their eyes, their gaze always lost, their eyelids heavy from having to look inward to find what they never imagined they’d miss this much. If they are writers, they do not write. Not now. They first need a job, a physical address, a first paycheck with which to send money back home. Not now. Why write? Nobody knows them here. Who would translate and publish them? It’s too soon. They’ve had no time to create community. They are surviving, and even those rules, they are still learning.

As I wrote those words, I was startled to realize that I am one of those souls—that the “there” I left is more a part of me than I knew, and suddenly I am an orphan, displaced, even though I own my own home within driving distance of places where everybody knows my name.

But it’s not enough. I will never again be home because home is a construction of a certain place, at a certain time, with a particular set of people who relied, or not, on each other in specific ways. And I will never again be a little Puerto Rican girl, sharing a home with beasts, the threat of violence always a cry away, and not just for six months out of every year.

I will never again be the young mom of girls arriving in Miami months after Hurricane Andrew, wide-eyed after having escaped a wave of gendered violence so bad that I once caught myself checking a dresser for fear a full-sized man had broken the bottoms of all the drawers to hide inside, ready to attack me, as had happened to other women where I lived. Within three months of that incident, I was gone and my long road of uprootedness had begun.

*

For the uprooted, a room of their own is not enough to write; her most important tool is not paper and pen or pencil, not even place or space. It’s memory. But from the moment she leaves, she is halved; her memories are tainted by sadness, by guilt, by relief cooked in regret. Who did she leave behind? If she was forced to leave, her sadness is unbearable. If she chose to, the guilt murders her daily. She doesn’t yet belong in the new place, but the old place is already dissolving, never to exist again. Not exactly. Plus, forget identity. Who is she, really? Her new environment knows nothing about her—just that she is a person who leaves.

And so, in this state of being, she tries to write. Isn’t that what you do? Why (even in small measure) you left? But she can’t. She doesn’t yet know the mechanics of writing while uprooted. She doesn’t know that first, she must craft a transitional identity.

“Latinx” is as good a label as any. But what does it (or any other identity based on origin) really mean? That is why she must redefine Latinx. Redefine it to mean “one with roots in a country with a history of colonization (and thus the Spanish language, the Catholicism, the rage against oppression), now sharing the immigrant experience in the US with others of similar historical DNA.” She has to do this if she is to reroot herself in the now, in the writing she came here to do.

Now comes the hardest part. She must look back. Remember. Tell herself her own story: why she left, why it was the best choice, who she was, who she wants to be. Is she responsible for giving voice to those she left behind? Must she write their stories? Here is where she must look around: she is not the only one who left. There may be others better suited to tell the history of her people, of her past. What she must do above all else is honor herself, write what is in her heart, trust that her roots will show up in what she willingly gives others: her art.

Meanwhile, she will set about creating a “home for now.” Thinking about it in this way, it won’t hurt so much when someone tells her to go back where she came from. And someone will. But. She decides not to dwell on that. Instead, she writes more, gives more of herself. She contributes by creating as much value as she can and making a gift to this country out of all of it.

Will all this make her any less uprooted? Probably not. But it will make it easier to write. And it’s okay to be uprooted when you’re a writer. Your new community has no borders.

__________________________________

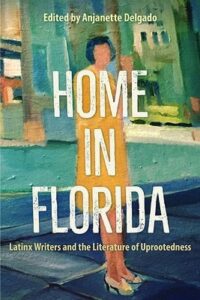

Home in Florida: Latinx Writers and the Literature of Uprootedness, edited by Anjanette Delgado, is available via the University Press of Florida.

Anjanette Delgado

Anjanette Delgado is a Puerto Rican writer and journalist based in Miami. She is the author of The Heartbreak Pill: A Novel and The Clairvoyant of Calle Ocho. She has written for the New York Times “Modern Love” column, Vogue, NPR, HBO, the Kenyon Review, Pleiades, the Hong Kong Review, and others.