On the Importance of Stories That Take Teenage Girls Seriously

Kaitlyn Tiffany Recommends Elif Batuman, Cadet Kelly, and More

As part of the research for my book, which is about fandom, I read a lot of archival newspaper coverage of concerts attended by teenage girls. When the concerts they were going to were Beatles concerts, in the early 1960s, it wasn’t so surprising that the journalists described the girls as hysterical—deranged?—participants in a “wild-eyed mob,” but I did find it odd when The New York Times was talking about the girls 50 years later as “squealers” and as embarrassing idiots, basically, who had “not yet decided that shrieking doesn’t become them.” Like me and my three sisters at the time, those girls were at One Direction concerts. (Personally I think we’re smart and charming.)

I don’t bring this up out of desire to hold onto a grievance. It’s objectively funny to wonder in a newspaper about what is and isn’t becoming for young ladies. And bygones are bygones—people aren’t really allowed to make fun of girls like that anymore, at least not in the paper of record. Still, part of what I wanted to do in my book was tell some other stories about who fangirls are and what they want. Through talking to them, I found that they were out to do really weird and interesting things, like most people are. They were very particular, which is the most thrilling type of person to speak with.

Now that the book is done and I have a lot of free time, I’ve been able to revisit some of my favorite fictional stories about young women (in books, movies, and one incredibly long TV show). In these stories, girls aren’t just “squealers,” but freaky and funny people with a lot on their plates. Sometimes they’re remarkable, other times they’re remarkably average. In one case, the heroine is an exceptional bummer (“the Gloomiest Child Queen”); in another, she’s a peppy blonde klutz. In all cases, these girls are taken seriously and their desires are the whole deal—the source of the story’s drama.

*

Lorrie Moore, Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?

In 1994, married and unhappy, Berie is eating brains in Paris (she doesn’t specify what kind) and “hoping for something Proustian,” meaning she’s smashing the brains against the roof of her mouth and praying it jogs some memories. When it does, they’re of the seismic summer when she was sixteen, slogging through a menial job with her best childhood friend.

In 1972, Berie and Silsby—yes, two incredible names—work together at an amusement park called Storyland, in the fictional town of Horsehearts. On their breaks, they chain-smoke in a covered alley called Memory Lane; in their off-hours they take their fake IDs to lakeside bars. They are sometimes joined by a teenage colleague who plays Bo Peep and is shown in flash-forward to have some dark life events ahead of her, but in 1972 is “tireless, ironical, and young.” (“‘Have you seen my fucking sheep?’ she’d ask.”)

Berrie is a ticket-salesperson, and Silsby is Cinderella, “the most sophisticated girl in Horsehearts, not a tough task, but you have to understand what that could do to a girl.” I don’t want to spoil what goes on between them because this book is short and everyone could read it today at lunch if they wanted to—they should. All I’ll say is that there is not really a “frog hospital” in a strictly literal sense, but… there is one in a more literal sense than you might guess.

Raw, dir. Julie Ducournau (2017)

Raw is my favorite movie. I saw it three times in the theater. It’s about a French teenager who goes to veterinary college and learns that she is a cannibal. (Her parents already know this, which is why they only ever let her eat mashed potatoes at restaurants.) The movie sort of positions cannibalism as natural and exciting, but not in an edgelord way. It’s just wild! “You have this feeling when you bite someone’s arm for fun that you want to go a bit further,” director Julie Ducournau told The Guardian during the publicity tour, objecting to audiences’ surprise and horror in regards to the cannibalism, basically suggesting that they were lying about being morally and physically perturbed. (There were some hokey claims of viewers fainting and throwing up at Cannes.)

It is a body horror movie, but most of that horror has nothing to do with eating people. It comes more from a full-body rash, from a bikini wax gone wrong, from a bad habit of eating one’s own hair, and from a really powerful sexual desire for a boy who is playing soccer. Who can relate?

Mustang, dir. Deniz Gamze Ergüven (2015)

In rural Turkey, five hilarious sisters with identical hair scandalize their grandmother, uncle, and busybody neighbors by playing a game of chicken-fight in the ocean with some boys—grandma describes this quite grossly as “your parts touching their necks.” This kicks off a new oppressive phase of their upbringing, in which they are made to wear “shit brown” dresses and stay inside at all times, but they don’t exactly take the punishments lying down. They rip the dresses and accidentally drop one out a window; they light a chair on fire, arguing that the chair is vulgar because it has touched their butts. They make their own gum and laugh their way through a “virginity exam.” (“We’re all made the same,” one sister says, to explain to the youngest why she wasn’t embarrassed to be naked in front of the doctor. “That’s not true,” another interjects. “You have one boob bigger than the other.”)

I have a soft spot for stories about girls living in a house—Pride and Prejudice, Little Women, The Real Housewives of New Jersey. I also like stories that acknowledge how a house full of sisters is tragic—one day you’re having a great time and then suddenly you’re watching them get picked off one by one. I’m not going to lie, this movie does not have a happy ending.

Elif Batuman, The Idiot

Literally everyone somehow ends up enjoying this campus novel (Harvard, lol) that takes place substantially through email and coursework. The protagonist, Selin, is obsessed with language and with a boy named Ivan who sucks in a pretty typical way. When this book came out in 2017, I was in a hopeless and confusing semi-romantic situation that took place almost entirely in iMessage, so I read it twice in two months and posted it on Instagram like everyone else. (Great cover.)

I recently pulled it out to read it again—in preparation for the publication of the sequel, and this time with the intention of paying closer attention to Selin’s friendship with her moral foil Svetlana. It warmed my heart to look back at what I had underlined, in forceful mechanical pencil, when my only interest had been in the torturous correspondence with the boy and how that might relate to my depressing, dime-a-dozen situation: “It was decreasingly possible to imagine explaining it all to anyone. Whoever it was would jump out a window from boredom.”

Cadet Kelly, dir. Larry Shaw (2002)

The 2002 Hilary Duff movie that was eventually reinterpreted as a queer romance and, yes, sure, military propaganda—was released during a golden age of Disney Channel original movies about girls plopped into extreme circumstances. This was the era of teenage Lindsay Lohan investigating her English teacher’s disappearance, as well as a re-interpretation of Twelfth Night set in the world of competitive off-road motorcycle racing, and also of Quints, a batshit movie about being a teenager whose parents suddenly have five babies.

In Cadet Kelly, Duff plays an artistic teen with great personal style whose mother gets remarried to the head of a military school—Kelly must transfer, and she must learn to get along with Christy Carlson Romano, a rigid student leader who is not penalized for referring to underclassmen as “maggots.” Of course, Kelly is not happy about this, but she makes it work because she must, for the sake of her mother’s fragile happiness. Adults are always needing things from children!

I feel like I don’t even need to explain the draw of this one. But Hilary Duff is my generation’s Sarah Jessica Parker—she is charm, she is comedy, she gives us complexity through froth. She is our sweetheart, and her dad falls off a cliff in the middle of her drill team’s dance competition. She rappels down and saves him… and makes it back in time for the grand finale.

Patty Hearst, Every Secret Thing

I’m not trying to be glib, but I ordered Patty Hearst’s 1981 memoir on Etsy (?) at the beginning of the pandemic because I genuinely thought it would have some bearing on the moment. (Trapped inside…) Well, it really didn’t, but it was a specific, fascinating read. The young heiress—with the help of a credited ghostwriter—shares every single moment of her experience being kidnapped in 1974 at the age of 19 by the hapless “Symbionese Liberation Army,” from the night they showed up at her house in Berkeley all the way through the legal battles resulting from her participation in some of their crimes. Don’t worry, there are some funny parts. (“We had a terrible go-round on the question of how much money my father earned. I simply did not know. I could not guess.”)

In her essay “Girl of the Golden West,” Joan Didion reviews the reviews of Hearst’s book, which largely agreed that she came off as inauthentic and was leaving something out. “What the something might have been, given the doggedly detailed account offered in Every Secret Thing, would be hard to define,” she wrote.

Truly: the book is almost 500 pages long and gives you everything you might want to know about how to lace a bullet with cyanide, or what kind of tea a captive might be served in a closet. If anything is left out, it’s probably Hearst’s personal reactions to the many ridiculous conversations and situations she’s placed in—but they should kind of be obvious. “I commented that I had never heard of mung beans,” she writes. “For that I was called a ‘bourgeois bitch,’ because, someone said, that’s what the poor people in America had to eat every night and I had not even heard of it.”

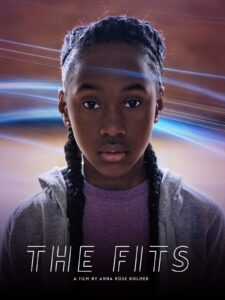

The Fits, dir. Anna Rose Holmer (2015)

I first watched this movie at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, which doesn’t even allow snacks in the theater, and was riveted. Set in Cincinnati, it follows an 11-year-old girl named Toni as she shifts her passion from boxing to dancing. She is in awe of the older girls on the dance team, so she has quite a time of it when some of them start having mysterious seizures—A terrifying metaphor for puberty? For gender? For transcendence through art? “There’s not that big of a difference between flailing and performing,” director Anna Rose Holmer told The New York Times. (A little cryptic.)

Make of it whatever you want, but don’t forget to chase it with the amazing New York Times Magazine story about its real-life source material—a wave of unexplained physical tics that showed up in girls at Le Roy high school in upstate New York in 2012. (Le Roy is about 45 minutes from my hometown, so this news story was a subject of fascination among my friends and family.) Though parents, teachers, and some experts were ready to be convinced that it was an incident of contagious female hysteria, the most likely explanation turned out to be a delayed reaction to the strep virus.

Jenny Hval, Girls Against God

Okay, I’ve only recently started reading this one. I think it involves witchcraft later on, but so far it’s about a “provincial goth” girl in southern Norway in the 1990s, who loves anger and resents that she isn’t allowed to talk about this at school (“We’re not allowed to say ‘hate’ unless it’s about Hitler,” she complains). Naturally, she’s getting into the metal scene. She’s very curt. Faced with a reading assignment she feels is beneath her, she refuses to finish the book: “I tell the teacher that it’s an insult to the brain, and the teacher gives me a written warning.” (One of several she will receive.) I’m loving it. I feel confident in this recommendation even if I wind up disliking the ending or the witch stuff.

Pretty Little Liars, created by I. Marlene King

What a show. It’s so scary. It’s pretty dumb. There are like 500 episodes and 1,000 different cell phones. I think there are arguments to make about its sociological critiques… of the “mean girl” trope or of our relationship to technology or something, but I don’t care. These are simply the hardest teenagers you’ll ever meet (played by 25-year-olds, naturally). They are aware that they could die. They learn that their parents are pieces of shit and they don’t really react.

They are not romantic about the nature of high school friendship (it’s clear they know they have nothing in common other than their many stalkers and their trauma) and they are very distrustful of the police. When Emily Nussbaum wrote her big essay about The Sopranos in 2007, she mentioned that it had the only opening credits so iconic that people still bothered to sit through them every single week. Maybe! Until Pretty Little Liars!

___________________________________

Everything I Need I Get From You by Kaitlyn Tiffany is available from MCD x FSG Originals

Kaitlyn Tiffany

Kaitlyn Tiffany is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers technology and culture. She was previously on the same beat at Vox’s consumer vertical The Goods, after starting her career writing about pop culture, fandom, and online community at The Verge. Formerly the host of the popular podcast Why’d You Push That Button, which considered the tiny technology decisions that have an outsized effect on our modern social lives, she lives in Brooklyn.