On the Iconic Iraqi Writer Who Modernized Poetic Forms

Fadhil al-Azzawi, a Countercultural Literary Force

Was Fadhil al-Azzawi better as a poet or as a novelist? His career spanned both realms, each a testament to the vitality of his modernism, his prolific literary output, and his commitment to the role of the free and independent intellectual.

There are those who prefer him as a novelist rather than as a poet. There are also those who consider him a truly exceptional poet, responsible for fomenting a revolution in the modern Iraqi ode, after its transformation at the hands of the 1950s pioneers (al-Sayyab, al-Malaika, al-Bayati, and al-Haydari).

In reality, however, it’s quite difficult to separate the novelist from the poet in al-Azzawi’s case.

The imaginative force of his novels could only have sprung from the mind of a poet who had from the very beginning embraced rebellion as his guiding principle. Setting himself free to explore the twisting and intertwining paths of life, al-Azzawi would forge an aesthetic and intellectual labyrinth carefully fortified with his own personal riddles.

These were his weapons of choice against a dark and enigmatic world: words and things clashing together, not in the service of a particular goal or consistent message, but to clear away something of the absurdity that pervades every aspect of our existence.

Al-Azzawi always had something to say about poetry, as if it were his own personal discovery, his special instrument for changing the world. Thus he was compelled to write his Poetic Manifesto, which was published in the journal Shi‘r 69 and signed by himself and three poets of his generation. The manifesto, with its obscure language and striking intellectual vision, performed a radical break not only from the modern poetic tradition, but also from the contemporary political reality, which portended revolutionary transformations.

At the time, al-Azzawi belonged—intellectually, at least—to the political Left. Yet his Poetic Manifesto, and the maelstrom of controversy it aroused, put him in a position that those in the traditional Left would eye with wariness and suspicion.

In his time, al-Azzawi was the model nonconformist: true to himself and the role of the intellectual as he envisioned it. In 1969, he published his fantastical novel Fadhil Al-Azzawi’s Beautiful Creatures. Evincing a radical individualism in conflict with the rest of the world, the novel understandably generated a good deal of mistrust.

It’s quite difficult to separate the novelist from the poet in al-Azzawi’s case.

Al-Azzawi was perceived as an enemy of the nation’s heritage. In a country ridden with partisan divisions, he stood accused of breaking from the established model of revolutionary commitment—then understood in its narrow political sense—and its prescriptions for the function of literature in society.

And yet, the suspicions he aroused did not faze him. He remained faithful to his writing, which he considered a form of salvation. He was a unique embodiment of the professional author in a society that never recognized writing as a profession.

The prevailing notion that writing could be no more than a hobby had led many talented authors to ruin. Therefore al-Azzawi worked in journalism, which he saw as a laboratory for new writing styles. It would become his means of transmitting his intellectual rebellion. His visionary ideas were steeped in a modern cultural sensibility of which so many were in dire need.

Al-Azzawi’s cultural style, aesthetic ideals, and literature were shocking to his contemporaries. When he left to study in Germany in the 1970s, he did not fall into obscurity like so many of his compatriots who, willingly or not, ended up outside the country. The works he published while in Iraq—the poetry books Greetings, O Wave, Greetings O Sea (1974), Travels (1976), and Eastern Tree, in addition to his two novels, Fadhil Al-Azzawi’s Beautiful Creatures and Cell Block 5—established his reputation as a controversial icon, while those he wrote abroad granted him a truly legendary aura.

Al-Azzawi’s ghost still haunts the notebooks of our poets.

His persistent literary output in the face of great adversity would prove inspiring to subsequent generations of writers. While he remained possessed by the magic of Arabic, al-Azzawi went beyond the confines of his language to compose poetry in English and German as well.

It might be said that his multilingualism led him to the abode of world literature, with its universalist perspective. Yet his universalist impulse also led back to his everyday existence. His novels Al-Aslaf (The Forefathers) and The Last of the Angels reflect his enduring attachment to his own roots.

Al-Azzawi published selections from his memoirs on the website Kikah. Though he never published these in full, his book The Living Spirit preserves an account of the cultural transformations witnessed by Iraq in the 1960s, in which he played a leading role. Just as a part of him remains tangible in all of Iraq’s modern literary transformations, so too shall another part of him remain forever beyond reach, an eternal enigma.

Al-Azzawi’s ghost still haunts the notebooks of our poets. For the generations that did not get to know him personally, he will remain forever like the father gone off to some distant, unknown land. Exactly like Iraq—especially Kirkuk—he possesses multiple identities. For Kirkuk, during the days of religious, national, and linguistic pluralism, was a source of great pride for him.

As a small child, the son of Kirkuk opened himself up to this wide universe of cultural pluralism, which he found operated as a sort of technical improvisation that he could connect back to his own personal universe. Kirkuk was a theater of languages interacting with each other in warm intimacy. Still innocent of the divisive notion of “citizenship,” the city’s spirit proclaimed tolerance and respect for the other.

Therefore, when al-Azzawi travelled to Baghdad with a group of fellow Kirkuki literati, they were warmly received as an authentically Iraqi phenomenon. Mouayed al-Rawi, Zuhdi al-Dawoodi, Anwar al-Ghassani, Father Yusuf Saeed, Jalil al-Qaisi, Jan Dammo, and Sargon Boulus—besides al-Azzawi himself—represented the diverse colors of Kirkuk’s cultural rainbow. Their international credentials, moreover, were reinforced by their command of English, and the presence of the British Petroleum Company in their hometown.

The “Kirkuk Group”, as they were called, breathed fresh life into the Iraqi cultural scene. Their significance can hardly be exaggerated, for al-Azzawi represented but one voice within this much larger phenomenon. Among his competitors was Sargon Boulus (1944–2007), whose impact on the modern Arabic ode was lasting and deep.

Al-Azzawi’s impact was of a broader nature, due to the diversity of his interests. Beyond the field of literature, he was concerned with humanity in general. As a result, he remained connected at a deeply personal level to those with whom his life intersected. His intimacy with others has persisted in spite of his long time abroad, which otherwise threatened his memory with oblivion, and the passing of friends. And so he remains a unique Iraqi icon.

–Translated from the Arabic by Ben Koerber

__________________________________

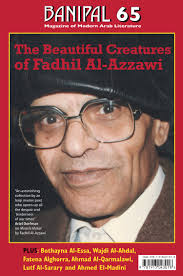

This article about Iraqi poet and novelist Fadhil al-Azzawi opens a special feature in the current magazine, Banipal 65 – The Beautiful Creatures of Fadhil al-Azzawi, on his writings of over more than half a century.

Farouk Yousif

Farouk Yousif is a poet and art critic, from Baghdad, Iraq. He studied Art at the Baghdad Academy of Fine Art and published his first collection of poems, Silent Songs, in 1996. Since then he has published six further collections of poetry, five books of art criticism and six travelogues. In 2006, he won the Ibn Battuta Travel Writing Award for Nothing Nobody. He currently lives in London and writes for Al-Arab newspaper. His book on New York, Following Lorca’s Steps, has just been published in Arabic, and excerpts from it will be published in Banipal 66 (Autumn/Winter 2019).