On the Historical Stigmatization and Persistent Vilification of Epilepsy in Literature

Louise Fein Considers How the Misunderstood Neurological Disorder Has Been Unfairly Portrayed in Popular Fiction

Neurologist Rajendra Kale wrote in 1997 that “the history of epilepsy can be summarised as 4,000 years of ignorance, apprehension and stigma, followed by 100 years of knowledge, apprehension and stigma.” In literature, the depiction of epilepsy, variously, as the vessel of the spirit of evil, the devil, or the divine is almost as old as the condition itself. Epilepsy, often in the past referred to as “the falling disease,” was named as such because during a seizure the sufferer fell to the ground to be closer to the Devil and Hell. The inspiration for exorcising the epileptic originates in the Bible, where Jesus heals a boy who falls to the ground with seizures by driving out the evil spirit who is controlling him (Mark 9:14-29). In Matthew 14-16, the epileptic boy is also described as “a lunatic.”

The idea that the mind of the epileptic is itself depraved, the person unable to control his or her evil mind to the extent that the spirit must be exorcised or the person themselves cast out and restrained in institutions to ensure the safety of the non-afflicted, persisted well into the second half of the 20th century. In William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, although 12-year-old Regan’s “possession” is by an evil spirit, the spirit manifests in part as seizures. In real life, the consequences of belief in the link between epilepsy and possession could be devastating. Anneliese Michel: A Story of a Case of Demonic Possession, written by Lawrence LeBlanc, tells the true story of a German girl in the 1970s who suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy, but was subjected to 67 exorcism sessions and eventually died in 1976 from neglect.

The belief that there is a link between criminal activity and epilepsy has a long history, too. Dostoevsky, who suffered from epilepsy himself, often used a clichéd version of the disease in his books. For example, in The Brothers Karamazov, Smerdyakov, an epileptic, murders his father, then frames his brother before committing suicide. Carmen in Raymond Chandler’s, The Big Sleep, too, encapsulates the trope of the epileptic character as an evil criminal mind. In this Philip Marlowe detective story, the epileptic Carmen turns out to be the murderer. She is highly promiscuous, morally depraved, and a criminal, murdering one of her lovers during a partial seizure. Marlowe promises not to go to the police if Carmen is sent to an institution instead. Michael Crichton’s The Terminal Man features a man who suffers from psychomotor epilepsy and blackouts. During his seizures, he is violent and attacks people. When he has a brain pacemaker fitted, he becomes addicted to the “shock of pleasure” he receives from the pacemaker and begins to initiate more frequent seizures as a result.

Conversely, there has been a long-held belief in the link between the epileptic and the divine, in particular, the ability to make predictions about the future. In Salman Rushdie’s Booker Prize-winning Midnight’s Children, a soothsayer on a rooftop in Delhi predicts the future of the yet-to-be-born protagonist before collapsing in a seizure. In his later novel, The Satanic Verses, Ayesha, an Indian peasant girl and a false prophet, has epilepsy. She entices her village to undertake a pilgrimage to Mecca, saying that they will be able to walk across the Arabian Sea, but they disappear. In the 1996 novel, Sweet Company, by Colombian writer Laura Restrepo, an “angel” who is in fact an epileptic man appears in Bogotá, where people believe his seizures cause thunderstorms and other catastrophes.

Despite advances in our understanding of epilepsy, these depictions in literature have persisted. Authors also tend to portray the seizures themselves in a misleading way. While the descriptions have varied from author to author, there is a tendency to describe the fit beginning with an aura, followed by a complete loss of consciousness and control, perhaps frothing at the mouth, then falling to the ground and the entire body trembling and jerking. Essentially a dramatic description of a tonic-clonic seizure (see, for example, The Big Sleep or the depiction in Muriel Spark’s The Bachelors). Despite the sameness of the portrayals, there are, in fact, over 40 different types of seizures, many of which are so subtle as to be barely noticed by the observer.

Authors also tend to portray the seizures themselves in a misleading way.

While things are much improved today, sadly some of these attitudes still persist, aided in part by epilepsy’s portrayal in popular culture. Having an epileptic child and experiencing first-hand the prejudicial attitudes still persisting in society, it was important to me to shine a light on the suffering people with epilepsy have received at the hands of others. By personifying epilepsy, I was able to explore not only the long-held misconceptions surrounding the disease, but also to shine a light on treatments as well as attitudes, and the terrible damage done to innocent people as a result of these age-old stigmas, fear and ignorance.

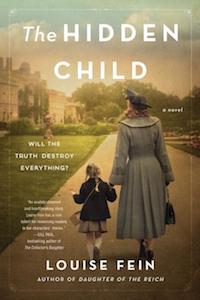

One of the characters in my new novel, The Hidden Child, is a young epileptic girl. The description of her seizures in the book is based on my observations of my own daughter’s seizures as a small child (she suffered from several different types, none of them tonic-clonic). It is perhaps understandable why, in the distant past, there was a tendency to believe an affected person was under some sort of “possession.” When my daughter’s illness was at its worst, I wrote a poem, a line of which concerned “the monster she carried inside” and that was the basis for the unique point of view in The Hidden Child—that of epilepsy itself.

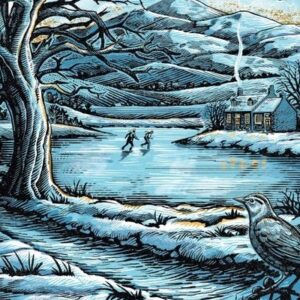

The Hidden Child is set in the 1920s and is concerned with the eugenics movement that sought to eradicate not only epilepsy but other diseases considered to be inherited. Epileptics were institutionalized in many countries well into the second half of the 20th century, and, as late as 1969 in Norway, it was compulsory for a person to disclose their epilepsy before marriage. If such information was withheld, the marriage could be annulled.

The ideas behind eugenics persist today, and we should always have one eye on the past, in order to avoid repeating its tragic mistake. The role of fiction in this, to me at least, is clear. Its power is to hold a mirror to society and human nature. I hope that future appearances of epilepsy in fiction will show a more nuanced and enlightened approach.

__________________________________

The Hidden Child is available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Louise Fein.

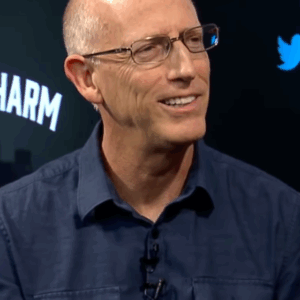

Louise Fein

Louise was born and brought up near London. After a law degree at Southampton University, she worked in Hong Kong and Australia, and enjoyed travelling the world before returning to London to settle down to a career in law and banking. She holds a master’s degree in creative writing from St Mary’s University, London.