On the Groundbreaking Documentary That Brought the Birthplace of Chicago Blues Alive

It Wouldn't Have Been Possible Without “Guitar King” Michael Bloomfield

It was 55 years ago in August that a groundbreaking documentary was created just west of the Chicago Loop in a scruffy neighborhood adjacent to the Dan Ryan Expressway. Its subject was, to a large extent, the city itself: its people, its commerce and, most importantly, its music.

Curiously titled And This Is Free, the 49-minute film was the creation of a 39-year-old news photographer from Oak Park named Mike Shea. Shea took pictures for the Chicago dailies and magazines like Life, Time,and Playboy. By 1964, he had become interested in making movies. The documentaries of filmmakers Richard Leacock and D.A. Pennebaker had greatly impressed him. Their “direct cinema” style of filming, made possible by innovative portable cameras and sound equipment, gave their movies an unstaged veracity that was new and exciting. Shea decided he too would make a film.

But a film of what?

There was a young musician that Mike Shea knew, a kid from the North Shore who was living in Sandburg Village. His name was Michael Bloomfield, and he had a reputation as a hotshot guitar player. A real live wire, the 21-year-old was always talking and carrying on, but Shea liked him, and had even let Bloomfield record in his West Huron St. photography studio. It was the guitarist who came up with a subject for Shea’s documentary.

“You gotta make a movie about Maxwell Street, Mike,” Bloomfield said. “The hustlers, the pimps, those alte kaker businessmen, man, it’s real street action. And the music! Blues, gospel, street corner shouters—it’s all down there on Maxwell.”

With money from an inheritance his wife had recently received, Mike Shea bought one of D.A. Pennebaker’s modified Auricons, a 16mm film camera that could be carried on the shoulder. Hiring University of Chicago student Gordon Quinn, himself a budding filmmaker, as his sound man, Shea began visiting Maxwell Street every Sunday morning.

He enlisted Michael Bloomfield as a “technical consultant” because Bloomfield knew many of the musicians who worked the market’s corners and alleyways and could get Shea permission to film them. Bloomfield himself brought in a friend, another U.C. student named Norman Dayron. Dayron had an interest in sound recording and had been working with Down Beat editor Pete Welding, recording blues musicians for Welding’s Testament Records label.

“I got a call from Michael,” Dayron said. “He said, ‘I’m working with this guy making a film and I want you to help me.’” Bloomfield asked Dayron to assist with a synchronization problem Shea was having. Norman joined the crew, and he and Gordon Quinn came up with a novel way to match the audio to the visual in Shea’s footage.

“We had to make, out of a flashlight head, a device that would put a tone on the tape—you know, like a slate. Gordon would have this flashlight head hooked up to the Nagra tape deck, and Shea would turn and film him, and he would push the button on the flashlight head and it would put this blink of light on the film. It would be totally in synchronization with a tone that got put on the tape.”

The filming began in mid-August and continued for as many as 16 weeks. Every Sunday, Shea, Quinn, and a few student assistants from the University of Chicago would meet at 5 am, just as the Maxwell Street market was getting underway. If the day’s shooting involved musicians, they’d be joined by Bloomfield and Dayron. Mike Shea would then shoulder his camera and walk through the streets, duck into alleyways and under back porches, or climb up on tenement rooftops to record the Maxwell’s bustling activity. Hours of footage were shot of eager merchants, pitchmen and their marks, con artists and hustlers, street preachers, food vendors, and bargain hunters of every age, ethnicity and economic status.

The movie received a few showings, but went largely unnoticed by critics and the larger film-making community.

With Bloomfield’s assistance, a substantial portion of those hours captured the market’s music. Many of Chicago’s famed bluesmen, including harmonica players Carey Bell and John Wrencher, guitarist and mandolin player Johnny Young, street singer Arvella Gray, and the legendary slide master Robert “Nighthawk” McCollum, were recorded by Shea’s camera.

There were impromptu street performances, electric blues bands with large, enthusiastic crowds of writhing dancers, gospel shouters and holy-roller proselytizers, even a young singer banging out a hambone rhythm on an empty cardboard box.

When Shea finished filming in early December, he had a vast number of exposed reels of film—many more than he needed for a short documentary. But Quinn and Howard Alk, an actor and one of Second City’s founders, set to work editing the footage into a cohesive whole, and by the summer of 1965, Mike Shea’s Maxwell Street documentary was completed. Its title came from a point-of-sale phrase used repeatedly by one of the market’s vendors, and the film offered an unvarnished portrait of one of Chicago’s long-standing traditions.

But the non-narrative structure that Shea used in creating the movie, its pastiche of sights and sounds in seemingly random juxtaposition, made the documentary challenging for most audiences. That the Maxwell Street market was seen as an eyesore and a haven for criminal activity by most of the city’s civic groups and politicians further tempered enthusiasm for And This Is Free.

The movie received a few showings, but went largely unnoticed by critics and the larger film-making community. Its tepid reception discouraged Shea, and he eventually put the documentary on the shelf and went on to other projects.

Listed prominently in the opening credits, though, was Michael Bloomfield’s name. He had been the impetus behind the selection of the market as Shea’s subject, and he was also the reason that the filmmaker was able to record some of the most remarkable footage of unfiltered blues and gospel music ever filmed. It was Bloomfield’s deep love of the music, his knowledge of its players and his innate charm and glib tongue that secured viewers a glimpse into the heart of those purely American art forms.

The young guitarist would go on to become one of the giants of 1960s rock, first as Bob Dylan’s electric guitarist, then as the fiery soloist with the Butterfield Blues Band, later as the creator of brass-rock with his own Electric Flag and finally as Super Session’s superstar. His contributions to American pop music have been well documented, but his role in the creation of And This Is Free has remained largely unknown.

The documentary itself remained essentially unknown, stored away and forgotten for many decades. That circumstance has happily been rectified in recent years, first with the commercial release of the film on DVD by Shanachie, then with a CD set of the existing audio recordings from Shea’s footage by Rooster Records, and more recently, by a posting of the film online. If you haven’t seen it, you’re in for a treat.

__________________________________

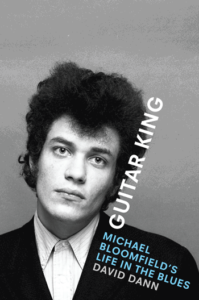

David Dann’s book, Guitar King: Michael Bloomfield’s Life in the Blues, is out now from University of Texas Press.

David Dann

David Dann is a commercial artist, music historian, writer, and amateur musician who worked for many years in the news industry, including serving as co-publisher of an award-winning Catskills weekly. Most recently, he was editor of Artenol, a radical art journal described by the New York Times as “a cross between The New Republic and Mad Magazine.” He has produced radio and video documentaries of Michael Bloomfield and served as a consultant to Sony/Legacy on their recent Bloomfield box set.