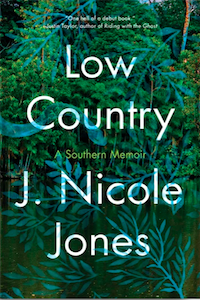

On the Familiar Ghosts and Family Legacies of South Carolina’s Low Country

J. Nicole Jones Considers a Lifetime of the Unexplained

and the Supernatural

Once down in the Low Country, I saw the ghost of a woman I knew well. Not the cool silver specters observed by men that portend danger and violent endings, but a beauty who basked in wide strands of sunshine and predicted nothing but herself. She walked slowly along the shore as if taking in the clear winter sky and soothing song of low-tide surf on the beach that connects the boardwalk with Ocean Boulevard on one side and with the Atlantic on the other.

It was the first day of a new year. An easy time to get lost in the portal crease between calendar pages, or any pages, really. Ours is a tourist town alive only half the year at most, and who is to say that spirits do not need a vacation every now and then like the rest of us? She did not see me as she had in life, and I froze breathless, unable to move for equal fear of her attention and her vanishing. I watched this figure as she strolled and smiled, a seductive curving form that might pass for the lolling dunes behind us or the sprawl of waves beyond. She looked in her white pleated shorts and pink bikini top like any other visitor in search of something from our beach to take home. Wherever that might be these days. While I breathe, I hope, says our humble state motto, but surely there is hope for the ghosts of South Carolina too.

I have seen a few such unbelievable occurrences and have heard of many more. Across inlets tinted the lavender gray of looming afternoon storm clouds and marshes fringed green and gold with reedy spartina grass, this coast has entertained the most distinguished of pirates and every sort of sea monster, from mermaids and megalodons to slave ships and surging tempests.

Now the history is hidden beneath the plastic indignities of scratchy Astroturf and fiberglass minotaurs that invite tourists to play miles of miniature golf courses, for which the city of Myrtle Beach is distinguished as the world’s capital. A selection of historical dinner theater that is awfully forgetful caters to out-of-towners with inelegant accents who come for tans and leave with tattoos. A coast is fundamentally a liminal space, I suppose.

Our family has made its living off the stories and legends of the Low Country since long before my lifetime.

With my brothers and cousins, all sons of sons except for me, I have searched for buried treasure rumored to have been hidden by the pirate Blackbeard under this looking-glass sand. When we did not find it there, we dug up the briny slime of pluff mud at low tide and stalked the pines at the edges of the family’s golf courses looking for relics of our history.

Under bedsheet tents printed with dinosaurs and aglow in candlelight, my dad and his brother, Uncle Leslie, brought to life sunken galleons, crumbled plantations, and cemeteries haunted by the eternally unfulfilled souls of lonely wives and lovelorn daughters carried away by sea or sickness. Vengeful spirit remains among the main opportunities for ambitious women in the Low Country, and I took note as the boys took cover.

I know several God-fearing folks who claim to have seen with their own eyes the Gray Man pacing the beaches of Pawley’s Island before hurricanes Hugo and Hazel. Some will say they’ve seen him before the lesser unnamed storms of recent years, though any kid here can tell you that is not how it works. If the laws are few and far between in South Carolina, the rules that govern our folklore are kept strict, and any ghost worth her salt respects such soundness. So you see, even as the law has little place here, a crooked logic carries sway.

Like many native sons and daughters, the Gray Man rouses for a hurricane, and it is a stroke of luck to be forewarned of approaching danger by whoever he was. Hold your breath when going past a graveyard, unless you want to breathe in a lost and lingering soul. Hang your empty bottles from tree branches to catch a stray evil eye. Paint your ceilings the calm, cool blue of a late-September sky after an almighty storm to trick the haints from coming out at night. It really is a lovely color. What is tradition if not a truce with the unknown, of which there isn’t as much as there used to be. Good ghost stories have disappeared as fast as decency in these times. Like a full-moon ocean wave or a tree branch in a hurricane, an authentic one will knock you over the side of the head. A sideways glance is the most graceful escape in the direct path of such forces, though it is a discipline to look away.

I have been gone 13 years, give or take some superstition. When I return, I tell myself only one story: that this is the last time, and this last time may finally end up as such, if I can look away. My nana, a witty beauty to match any Mitford sister and with more common sense than the bunch, has told me that I talk like a Yankee now. She forgave this ugliness and all the rest. It is only in conversation with her, whose drawl is as deep as her memory, that my own accent creeps out from wherever it lies. Under tongue or heart, depending on mood or drink.

Vengeful spirit remains among the main opportunities for ambitious women in the Low Country.

I come from a line of women for whom being walked all over and jumped on for the fun of cruelty was progress. The ironing out of accent was a way to fool myself into believing that I could be different than those women who suffered to make me. If I could have painted the roof of my mouth that lovely shade of haint blue to scare away the ghosts of women I did not want to be, the women I came from, I would have licked clean the brush.

I was supposed to be a boy, declared both a doctor and the family tree. It was impressed upon me that I was wanted however I came out, but I have wondered if this aberration rooted in me from the beginning a sense of indignation and unbelonging. The near-miss is a favorite trick of fate, and I always knew that being a girl meant hurting for what my brothers didn’t realize they had. Remarking upon this or any injustice was considered rude, I learned fast. My unease did not matter, so long as I was seeing to the ease and comfort of those around me. A lesson I hated to see practiced by my nana and mom, but found myself following.

Nana didn’t keep pear trees or hang trinkets from any ancestral cedar, but an ample magnolia stands skyscraper-tall in her backyard. From the top branches, you can see clear across to the beach and back a few centuries. What is now King’s Highway, still the main road in town, was once the route George Washington took when he visited Long Bay, as Myrtle Beach was known in 1791, and the road was named in typical backward civility for the new republic’s first president. Only once in my lifetime has the tide flirted with the roots of our Great Tree, and no storm has yet knocked it over, so who knows what’s up there. Memories woven between branches alongside the other forgotten junk. Swing ropes and water guns and toy action figures. Children are all born pagans, inspired by season, sin, and blood sacrifice.

My parents moved us away from Myrtle Beach when I was in high school, and Charlotte, North Carolina, may as well have been New York City. While my childhood classmates became teenage mothers and drug addicts or both, I was sent home from my fancy college prep school, having applied and tested for admittance as my lone act of teenage rebellion, for wearing overalls. I got made fun of for dressing and talking like the hick I was.

In a lonely flashlight-lit blanket tent, I read aloud Their Eyes Were Watching God over and over to comfort myself in the more familiar realm of put-upon women who talked in the melodies of my nana, a music that I knew from watching her could cushion the severest of blows.

I didn’t say much in school, but when I did, it was always the right answer, delivered in perfect television neutral. I was experienced at ignoring greater meanness. Rising above, as Nana would say. The name-calling, classroom hair-pulling, being tripped and pushed in hallways. These were small sufferings and worth the tolerating, if this fancy school helped me to escape a fate as vengeful spirit trapped by the stories I knew by heart. A Myrtle Beach education would not get me where I wanted to go, and though I wasn’t sure where that was, I knew that it had to be different and far away.

More than a decade after graduating from the fancy college prep school, during a time of devastating grief, I saw weekly a young woman who called herself a healer. In a railroad apartment in Brooklyn, the walls adorned with her own trinkets of worship, we discussed why I left a safe and salaried magazine job, how my writing progressed or didn’t, and the things I tried to keep hidden from everyone else I knew. Our sessions were a relief and a terror. I described ghosts I was not sure I had seen and received knowing nods and leading questions that made me feel, for an hour a week, less alone. Were those really the voices of loved ones long gone who called out my name in subway cars and expensive restaurants and while I brushed my teeth?

She held her palms an inch over my navel for long periods or pinched my toes following a particular order, as I held cool white stones of differing shapes that were painted in pretty patterns of smiling suns and dreamy-eyed prancing jaguars. She said these stones were from the Andes, and I felt it impolite to press.

“There, you see,” she sometimes declared without elaboration after such a performance.

More than once, she asked if I knew the tall man with the blue eyes who always stood behind me. One session, she informed me that I had somehow healed all the women I had ever been, as well as all my grandmothers going back to Eve, and I wish that I had asked her how. I began to feel unsettled less by my supernatural company than by her earthside acquaintance. I came to understand what it was I wanted from my own voice and never went back.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Low Country. Used with the permission of the publisher, Catapult. Copyright © 2021 by J. Nicole Jones.

J. Nicole Jones

J. Nicole Jones received her MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Columbia University, and has since held editorial positions at VICE magazine and Vanity Fair. Her viral essay defending the art of memoir, "Why's Everyone So Down on the Memoir?" was published by the Los Angeles Review of Books and Salon, and her reviews and other writings have appeared in magazines including Harper's. She grew up in South Carolina, and now lives in Brooklyn and Tennessee.