On the Decision to Publish the Largest Leak in the History of American Power

When the Washington Post Printed the Pentagon Papers, It Changed American Journalism

Maybe it’s a generational thing, but my eyes glaze over at the first sight of those words: Pentagon Papers. Before I knew [Washington Post editor] Ben Bradlee, whenever I saw a reference to them in a book I would reflexively start paging through to see how long it would be before the chapter ended. Whatever I learned about them never seemed to stick. Most people I know don’t really have any sense of what they were, or why they mattered, beyond the facts that they were about Vietnam and that a man named Daniel Ellsberg leaked them.

The truth is that to understand why Ben cared about them, you don’t need to know a whole lot more than that. But, for posterity, the Pentagon Papers were the 47 volumes of a top secret internal history of the Vietnam War, commissioned by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in 1967. Ellsberg had been an analyst at the RAND Corporation who worked on the compilation of the papers but subsequently underwent a personal conversion about the merits of the war. He thought that if the American people really knew what was going on in Vietnam, they would rise up to put an end to it. He decided to leak the papers, first to Senator J. William Fulbright, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. When Fulbright didn’t do much of anything with them, Ellsberg turned to The New York Times.

The most important revelation that the Papers contained seems now to be a kind of quaint confirmation of the obvious: the government, under both Democratic and Republican administrations, had routinely, and seemingly as a matter of policy, lied to the American public about the Vietnam War. Bombing missions that had been disavowed by presidential candidates were in fact being planned at the very moment of disavowal, by those very candidates. More Americans were dying than anybody knew. There were entire bombing campaigns, in Cambodia and Laos, that had never been reported. Though the media had harbored suspicions about all of these things, the Papers confirmed those suspicions on a scale that even cynical journalists hadn’t quite imagined.

I had always assumed that President Nixon reacted so aggressively to the publication of the Pentagon Papers because they were made public in 1971, and therefore must have embarrassed his administration. It was actually quite the opposite: the Papers contained no information at all about the Nixon administration. They had been delivered to McNamara’s successor as defense secretary, Clark Clifford, five days before Nixon’s inauguration in 1969. Nixon was apparently quite pleased at first with how poorly the papers reflected on the Democrats, particularly his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson. It was only when he realized that he could find his own presidency damaged by similar leaks down the road that he decided to take action, thus setting in motion the Shakespearean mechanics of his own demise.

What mattered to Ben about all of this wasn’t the substance of it. Ben cared only that Ellsberg had decided to leak the Papers to The New York Times. In the spring of 1971 everybody at the Washington Post had been hearing for weeks that the Times was planning a major scoop, but nobody knew what it was. On Sunday, June 13, 1971, after months of top secret preparation—reporters working from an undisclosed hotel room, security guards at the door—the Times finally dropped the bomb.

This was the kind of thing that drove Ben wild. His mission, from the moment he walked into the Post’s newsroom as an editor in 1965, was “to get the world to refer to the Post and the Times in the same breath.” That was his definition of excellence. Sometimes he would say publicly that his goal was to have “the best reporter on every beat,” which was true. But the main reason he wanted the best reporter on every beat was so that he could stick it to the Times.

Now the Times had him licked. The only way for the Post to cover the story was to rewrite the Times on its own front page, the bitterest of pills. Ben has a flair for melodrama, and he always says that there was “blood on every word” of the story that ran in the Post that Monday. (“You know how grand he is,” one Post reporter said when interviewed about it later. “I don’t know what the hell he said. It was a professional kick in his face, and he didn’t make any bones about it.”)

After two more days of the same routine, big stories in the Times and baleful rewrites the next day in the Post, Ben finally caught a break. The Nixon administration, claiming national security privilege, had secured an injunction against the Times, restraining them from publishing any further classified material. This marked the first time in American history that the government had ever been able to enjoin, or prevent, a newspaper from publishing in advance. The granting of the injunction posed a series of First Amendment issues, and the Times immediately challenged it.

The break gave the Post an opportunity. Ben Bagdikian, the National editor, knew Ellsberg. On Wednesday of that week, he received a cryptic call instructing him to fly to Boston, where Ellsberg was waiting for him. Ellsberg was worried that the Times had been silenced, and he wanted the information out. He forced Bagdikian to extract a promise from Ben that the Post would run the Papers if they had them, and Ben relayed his assurance that they would. Bagdikian returned the next day with 4,400 sloppily copied and out-of-order pages, a subset of the original seven thousand that the Times had received.

The large cardboard carton, full of small, disorganized bundles of paper tied together with string, sat in its own first-class seat on the flight down to Washington.

Fearing that the Post newsroom would be too public a place to review the documents—they didn’t want to be enjoined before they’d even started—Ben summoned top editors and reporters to his house in Georgetown. The Times had taken nearly three months to comb through the papers and to determine how to present the material they contained. The Post didn’t have that kind of time. To stay ahead of the government and the rest of the media, Ben and the other editors resolved to put out a story the very next day. Bagdikian arrived at Ben’s house from National Airport at 10:30 on Thursday morning. They had roughly nine hours until the first edition deadline.

Ben calls it “bedlam.” There were papers all over the place. The reporters were sequestered in Ben’s library with their typewriters, trying to hammer out early drafts of stories based on whatever scraps of information they could process in so short a time. The lawyers and editors convened in the living room, to figure out exactly what they could and couldn’t (or would and wouldn’t) publish.

Chalmers Roberts, a veteran reporter and one of the fastest typists on the staff, had begun to put together a story about the Eisenhower administration’s efforts to prevent elections in North and South Vietnam in 1954. As Roberts put it in a private interview some years later:

I said, “It’s not going to be sensational, but it will be different, it’s something the Times hasn’t printed.” That’s what Ben wanted, so I am printing something those bastards hadn’t printed. Because Ben is a terribly competitive guy, as you know.

Ben wasn’t interested in the issue at all. He was interested in the journalism. He says he has no politics, he doesn’t care whether the president is a Republican or Democrat. It’s true. It’s hard to believe about him, but it is true. . . . [H]e really is apolitical and he wanted good stories. He was still trying to make it. He was not the Ben Bradlee of Watergate at this point. We gotta think of him in a different context.

“It was an almost personal thing,” one editor said of Ben’s approach to the story. “It was almost manhood on the issue, it was macho.” Phil Geyelin, the editorial page editor, said that as Ben wandered between the reporters and the businesspeople it was as if he were back in the locker room at St. Mark’s prep school. “Bradlee was go,” Geyelin said. “That was his first instinct and I think it was his instinct all along.”

As the day wore on, Ben and the rest of the news side began to realize that the decision to publish wasn’t going to be automatic. For starters, the Post’s lawyers didn’t believe that the government would make false claims about national security privilege just to cover its own ass. The implicit assumption was that the government did what was right, that the president was infallible, trustworthy, deserving of the benefit of the doubt. This is one of the hardest aspects of the story to believe, 40 years later.

One of the more convincing arguments that the lawyers offered was that the Times had already been enjoined. The Post couldn’t claim that they didn’t know what the stakes were. There was language in the statute about “willfully” publishing material that could be “used to the injury of the United States,” and that now meant something different to the Post than it had to the Times.

And if that weren’t enough, the Washington Post Company, which in addition to the newspaper included Newsweek, three television stations, and three radio stations (among other holdings), had gone public two days before, offering $33 million worth of Class B common stock. If the Post were to be charged with a crime for publishing sensitive information, the underwriters of the offering might back out of the contract. This would cost the company money in the short term, but more to the point it would put the entire strategy and public position of the corporation in jeopardy.

Over the course of the afternoon, positions sharpened. “We were not doing very well in the argument,” Ben told me. Various compromise strategies floated around, including one in which the Post would notify the attorney general of what they intended to publish and then allow the Justice Department a day to respond. The reporters didn’t like that strategy much. One piped in, constructively, “That’s the shittiest idea I’ve ever heard.” Chal Roberts threatened to resign.

Word that the Post had the Papers was already starting to travel. If they didn’t print what they had, people would know—and the emerging reputation of the Post as a hard-charging, take-on-all-comers newspaper would suffer. “Here was this big new hotshot who was supposed to take the Post into the Promised Land,” Ben would say later, imagining what the line on him would have been, “and yet the first time he had any kind of challenge he caved.”

Late in the afternoon, somewhat desperate, Ben realized that the only person who could help him was his best friend, the famous trial lawyer Edward Bennett Williams. Williams was a grand Washington character, another larger-than-life guy, and one of a small number of people who could reasonably be called Ben’s peers. They first met in the late 1940s, when Ben was a court reporter for the Post and Williams was an up-and-coming defense lawyer, and they had stayed friends ever since. Williams was working a case in Chicago at the time, but Ben eventually tracked him down by phone:

Edward Bennett Williams, private interview, late 70s, undated:

He outlined the case, and then I said, Bradlee, you and I have been friends a long time—and actually our friendship went back to 1949—and I said it’s the first time I’ve seen you so far behind, it’s 21–0, it’s the fourth quarter, and there are eight minutes to go, and you better get going. . . . I’d been watching [this] city for about 30 years, and I’d been watching responsible and respectable journalists tell the Congress to go to hell and to go fuck themselves, and every journalist, at a moment of crisis, if he was respectable and the Congress was pressing for information said, you know, go to hell. . . . Congress always [lost] its guts when it comes to taking on the press. [And] that’s what I really was telling him. I guarantee that the Nixon people haven’t got the balls to go after you, because Nixon doesn’t have the balls to go for you. . . .

It was a political judgment and not a legal one, and I just knew that Nixon didn’t have the guts to go after them, therefore in this town you went with it, you didn’t sit there and be indecisive, you went to it, & you put the ball in their court.

Ben’s summary of this conversation was that Williams had told him, “Fuck ’em, your job is to print it.” The call bucked him up, right when he needed it. He also knew that Kay Graham respected Williams, and that Williams’s support for publishing would give him a card to play during what was rapidly shaping up to be the most important up-or-down phone call in the modern history of The Washington Post, placed later that evening from Ben’s living room to the home of Kay Graham.

That evening, Kay was throwing a retirement party at her house for Harry Gladstein, the Post’s circulation manager. She had known since that morning that they had the Papers, and that various editors and reporters and business types had congregated at Ben’s house to hash it out. But she hadn’t realized how serious it was getting. It began to dawn on her only late in the day, when Eugene Patterson, the Post’s managing editor, arrived at the party and pulled her aside.

“This problem is going to come to you,” Patterson told her. “You’re going to have to make a decision. And when it comes to you, the Post’s immortal soul is going to depend on your decision to print.”

“Oh God, no!” Kay said, somewhat stricken. She hadn’t expected a decision of that gravity to fall to her alone.

She went on with the party as planned. Right in the middle of her toast to Gladstein, as she stood on her back porch addressing the assembled guests, the call came from Ben’s house. This was it. Kay wanted to finish her speech but was told there wasn’t time, they needed her right away. She wrapped it up and hurried in to the phone. First on the line, by himself, was Fritz Beebe, the chairman of the Post Company, who had been at Ben’s house for most of the day. He was an old family friend of Kay’s, and he had been her father’s estate lawyer. (“Old Man Meyer,” as Ben always calls him, had bought the

Post at auction in 1933.) After Phil Graham, Kay’s husband, had died in 1963 and Katharine Meyer Graham had taken over the reins at the Post, Beebe’s had been the one shoulder she could always lean on. His advice meant more to her than anybody else’s.

“He crushed me,” Kay later told Ben, of what happened with Beebe on the phone. She and Beebe had never been apart on anything before. She assumed he would say, “It’s all right, go ahead and publish,” but he didn’t. What he said was, “I guess I wouldn’t.”

Ben, editorial page editor Phil Geyelin, and deputy managing editor Howard Simons came on the line. “I was ready to beg,” Ben admits. “I would have done anything to get it published.” He reported that Williams had told them to go with it, that they couldn’t afford to wait. To fail to publish would indicate to the world that there were “considerations other than news that guided our decision-making,” as Ben later put it.

Kay sensed that Ben was under enormous pressure, that the newsroom was going to go apeshit (her word) if she said no. She asked Geyelin what he thought. He said that with everything hanging in the balance he knew it was a tough problem for her, but that he thought they should publish.

“Well, it could destroy the newspaper,” she said bluntly.

“I’ve heard that in the argument,” Geyelin told her, “and I can’t easily dismiss it, but there is more than one way to destroy a newspaper.”

The answer could come only from Kay. It was her family fortune, her newspaper. The fact that Beebe hadn’t slammed the door as firmly as he might have had given Ben hope, but after he had made his case there wasn’t much more he could do. She knew where he stood. The editors fell silent on their end, and so did Kay on hers. The sound of music from the party in Kay’s garden drifted in and out over the open line.

“In a real sense,” Ben would say in a speech a few years later, of the moment that followed, “it marked the beginning of the journey which placed the Post once and for all on the cutting edge of history and of journalism. Throughout 1973, I was asked to define the key moment in our coverage of the Watergate matters, the one moment when we took an irrevocable decision. The answer is plain to me: the moment when Kay Graham said, ‘I say we print’ the Pentagon Papers.”

Kay agreed with that, particularly in hindsight, but later she needled Ben about that speech. That wasn’t exactly what she had said, she finally told him, during one of the interviews for her memoir.

“What’d you say?” he asked.

“I just said, ‘Oh, go ahead, go ahead.’”

“I couldn’t say, ‘She moaned, “Oh, go ahead, go ahead.”’”

“I did, but I didn’t moan,” Kay protested. “I just said ‘Go.’ I mean, I was so tense that I would—the idea that I would say, ‘I say we print . . .’”

“All I remember is hanging up the phone so fast,” Ben said. “Before she changed the wording?” an observer of the interview asked.

“Yes,” Ben said.

“After you hung up the phone,” the observer asked, turning to Kay, “did you have any regrets?”

“No,” she said.

__________________________________

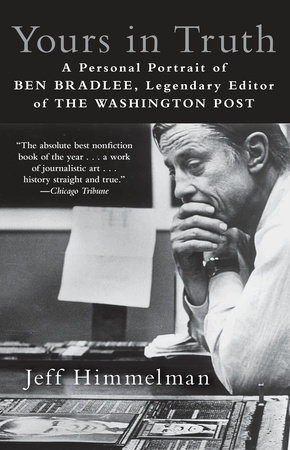

From Yours in Truth: A Personal Portrait of Ben Bradlee, by Jeff Himmelman, courtesy Random House. Copyright 2017, Jeff Himmelman.

Jeff Himmelman

Jeff Himmelman is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine, where he has been a finalist for a National Magazine Award; his writing has also appeared in New York, GQ, Washingtonian, and The Washington Post. His work with a team of reporters at the Post helped the paper secure the national reporting Pulitzer Prize for its post-9/11 coverage. He is also a professional musician who writes, records, and performs under the name Down Dexter. He lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife and three daughters.