On the Celibate Love Affair of Nora Ephron and Mike Nichols

Richard Cohen Remembers a Power Couple That Never Was

“Marlon Brando’s gay, everybody knows that.”

Nora said that one night in my house in Washington. I can’t remember how Brando’s name came up, but there it was, this startling (at the time) piece of information, so inside, so unknown to the general public, who considered him—fools that they were—a womanizer of great repute. I can remember exactly where I was at the time. In the living room. Standing in front of the sofa and to the right. The remark hit with the force of a dumdum bullet. Marlon Brando’s gay? Who knew?

Everybody, it turned out. Everybody knew. And whether they did or they didn’t, whether it was true or not, was totally beside the point. When Nora said one of these things—and she said them quite often—she did not do so with any sort of tentativeness, with hesitation, with the suggestion that this might be the rawest gossip and possibly wrong, but with a firmness and robust confidence that transformed the gossamer of hearsay into something chiseled into the frieze of a Greek temple. It was beyond dispute. Behold what she knew and behold what you didn’t. You knew some things. She knew everything.

Scandal itself has since been diluted. Homosexuality is no longer considered outré. Premarital sex is now passé, as are open extramarital affairs. Ingrid Bergman’s affair with the director Roberto Rossellini—they were both married to others at the time—all but had her banned from America. Ed Sullivan would not have her on his popular and influential TV show. Nowadays, she would be a sought-after guest.

The names that dropped from Nora’s lips were never drumrolled—not even preceded with a modest cough. They were simply stated. They were inserted here and there in sentences or used, with appropriate understatement, to clinch an argument. As far as I could tell, Nora never met someone famous for the first time. They had somehow always been present in her life. I can be excused for thinking that Mike Nichols was her childhood friend, that they had met at camp or even earlier, in Berlin, where she had never been—something like that. His name, when rarely invoked, was never accompanied by the unheard rumble of an organ, a trumpet voluntary of a buildup, but by the same matter-of-factness that made Marlon Brando gay.

Mike Nichols was in a singular category. Nora had a special relationship with him that was rarely mentioned. If she went to the Fifth Avenue apartment he shared with Diane Sawyer, she never talked about it. If they had lunch, she said nothing. If he warned her off a project under consideration, she was mum. If he did like a script, loved a script, improved a script—whatever—I knew nothing about it. Nora and Mike were celibate lovers.

Back when Nora had first approached Nichols and asked him to dinner, he had not yet reached cult status. That would come at the end of the decade when he directed Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and, more important and creatively, The Graduate, for which he earned an Academy Award. For both Mike and Nora, their meeting was something like love at first sight. Mike “got” Nora the way he had gotten Elaine May. “I instantly recognized a kindred soul,” Nichols said.

They had their own language, I think—a matter of nods and frowns and common cultural references. They knew whose marriage was a sham and who could not act and who had a bad drug problem. They knew the business—the business of movies and the business of theater and, because they were hyperventilating readers, the business of books and magazines. They had words, a torrent of them, but they talked also in shadows and in knowing they were both smart—but neither smarter than the other. They learned from the ricochet.

At that point in Nora’s career, Nichols loomed large. He was no mere film person, no Beverly Hills-Brentwood person, but someone who while recognizing the pleasures of Los Angeles preferred the stimulating abrasiveness of New York—just as she did. He was a figure of the theater—just as her parents had been before and after their movie careers. He had been a performer, an actor, an entertainer, and he had about him the air of the worldly German-Jewish intellectual, a man familiar with all the Marxes—Karl and Groucho and the boys—and someone who appreciated depravity. He had come to America from Nazi Germany on a boat that delayed its departure for a broadcast by Hitler.

Nichols’s instant infatuation with Nora had a precedent: Elaine May.

Here, also, was a very smart, dark-haired Jewish girl who not only could make a joke but get one, too. Nichols and May had created a pioneering and astoundingly successful comedy act and had had a brief romantic involvement. But the essence of their relationship—and of their act, which had originated in improvisation—was a kind of cerebral chemistry that had become apparent shortly after they bumped into each other in a Chicago train station. May, whom Nichols had met just once before, was sitting on a bench.

“May I sit down?” Nichols asked, affecting a Russian accent.

“If you veesh,” May replied, and the rest, as the cliché goes, is show business history.

Both Nora and Mike had a surfeit of talent, almost too much to handle, big and small ideas sloshing around in their brains, searching always for the meaning—the hidden meaning—of anything, its essence. Nora and I would sit and discuss something for what seemed liked hours, searching for the point—the point of a column, the thing that was hidden, the thing she could reveal, the point, the point, the point—while Nichols, with a wry observation, could get to the essence of a play or a movie with a snap-of-the-fingers metaphor that materialized even as he spoke it, and his actors immediately knew what the point was.

I met with Nichols from time to time, nearly always at Nora’s suggestion. I had a script I was pushing, an idea that was perking. He always read my stuff, sweetly passing—“It’s very, very good, Richard, but not for me”—and once saying, astoundingly, that he wanted to make a movie with me and Nora. I was flattered, but not quite convinced. Whatever my talent, I was above all Nora’s friend. And he loved her.

Somewhere along the line, Nora’s relationship with Mike reached an inflexion point. The mentor (Mike) and the mentee (Nora) became near equals, although Mike always remained the dominant one. Mike sought Nora’s counsel, but he always remained the one who had made more successful movies, more successful plays, and, of course, had been an entertainer. What Nora lacked in résumé, she more than compensated for in decisiveness. It could be as good as wisdom.

But their relationship did not start on an even keel. After all, it was Nora who came to interview Mike, not the other way around. It was Nora who went to Mexico to write about the famous director, the man who was doing what she’d always wanted to do. So it was Nora who sought approval from Mike and who, in the way she judged these things, did not get it back. Catch-22 was over. It was in the can. Nora and Mike had become close. Yet he was not inviting her to dinner.

So Nora asked Mike to lunch. They met at a place on Madison Avenue, across the street from the Carlyle Hotel, where Nichols was living. Nora said there was something she wanted to talk to him about. “And I said, of course. And I said, what do you want to talk about?”

She burst into tears.

“‘I’m not on your A-list.’”

“What are you saying? I don’t have dinner parties. I live in a hotel.”

Nora’s belief that she had not made Mike Nichols’s final cut was a rare false reading on her part. It was also additional evidence, if any be needed, of the centrality of the dinner party in Nora’s thinking. It seemed inconceivable to her that Nichols was not giving dinner parties; it was only conceivable that she was not being invited. It’s actually inconceivable that Nichols would have ever had a dinner party without her.

In time the mentor and the mentee fused. On a given day, one became the other, and just as Nora would look to Mike for his experience—he was, after all, older and already established when she was starting out—he learned to rely on her, her judgment, and the ferocious certainty of those judgments. They usually talked several times a week, not always about work, but often about food—the hot dogs from Nate and Al’s, for instance, and were they, as Nora insisted, the best. They reviewed various ice creams and restaurants as well, and, knowing Nora, the floundering marriages of people they either knew or heard about. They were both great gossips, not because they were vindictive or spiteful but because gossip was theater by another name. Such characters! Such behavior! Who could have guessed? Not in your wildest dreams. Actually, only in your wildest dreams.

As close as they were, though, Nichols, too, was kept in the dark about Nora’s condition. He later accepted her decision with equanimity; she had not only done the right thing, but—should there be any doubt—in matters such as this, Nora always did the right thing. Somewhere toward the end, though, Nichols learned that something was wrong. They were planets in the same showbiz solar system—and Nora, inexplicably, went dark. She was working with the movie and stage producer Scott Rudin and he couldn’t find her. He checked with Mike. Alarmed, Mike called Nora. She lied, and then quizzed J.J. about the source of the leak.

Near the very end, Nora’s son Jacob got in touch with Mike. Nora was dying. From the hospital, I conferred with Mike. There was this matter of a memorial service. Mike was to speak. I was to speak. He wanted to talk about that. He was distraught—adrift. I felt the same, but Nora’s condition was not a surprise to me. It was, though, to Mike. His despair was palpable. He was disconsolate, and nothing he was in life seemed to matter—not director, not producer, not writer, not intellectual, not entertainer. Momentarily, his confidence was gone. His voice wavered. He was 81 and in bad health.

A bit later, the phone rang. I was in the hallway of New York Hospital, a pace or two down from Nora’s room. She had just died. It was Mike. His voice broke.

“What are we going to do now?”

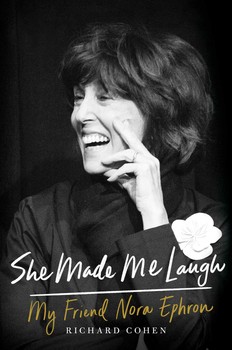

From SHE MADE ME LAUGH. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright 2016 by Richard Cohen.

Richard Cohen

Richard Cohen is a nationally syndicated columnist for The Washington Post, where he has covered national politics and foreign affairs since 1976. He has written for numerous publications, including The New Republic, The Nation, Esquire GQ, and The New York Review of Books. He has received the Sigma Delta Chi and Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild Awards for his investigative reporting.